As far as brief concerts on ESPN go, Kendrick LamarÔÇÖs halftime show for college footballÔÇÖs national championship went about as well as possible. Held in AtlantaÔÇÖs Centennial Olympic Park, the eight-minute show breezed through four songs (ÔÇ£DNA,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Element,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Humble,ÔÇØ and the new ÔÇ£All the StarsÔÇØ) while displaying the limitations inherent to mainstream television: Listeners accustomed to the uncut DAMN were introduced ÔÇö unless theyÔÇÖd already purchased the clean version ÔÇö to unfamiliar versions of familiar hits. For all his focus on the sacred, KendrickÔÇÖs hardly been an artist to eschew profanity in his lyrics, and the absence of foul language left an odd impression. Flows were curtailed, rhetoric softened beyond recognition: If there was anything to recognize, it was how little television had contributed to the rise of contemporary hip-hop, and how little overlap there was between their standards and practices.

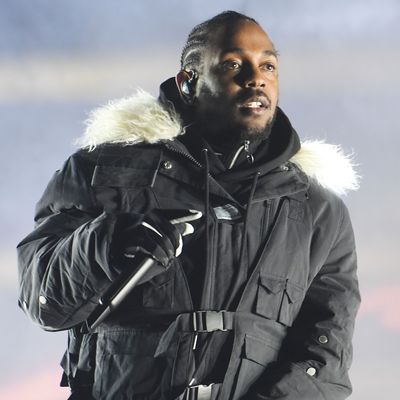

Fans expecting anything more than what ESPN and its parent corporation Disney would give were sure to be disappointed. The smart thing was to reduce anticipation and take pleasure in lesser details: the artistÔÇÖs spiffy winter coat, shots of delighted audience members, neon Chinese characters for ÔÇ£humble.ÔÇØ Certainly anyone looking forward to a polemical statement ÔÇö President Trump was in attendance at the championship ÔÇö was going to be disappointed. Sparks might have flown if the two had been in the same building at the same time, but that was never the case: Trump left after the first half of the game, which was held in nearby Mercedes-Benz Stadium, not in Centennial Olympic Park.

Unlike, say, Eminem, KendrickÔÇÖs not the sort to hurl verbal haymakers at the president without a larger plan in mind. More strategic and more patient, he only acts when the timing is perfect and does everything he can to orchestrate situations to his advantage ahead of time. Given the circumstances, lambasting Trump would only have been read as inopportune grandstanding. The smart thing to do was to take as much as he could get, which happened to be a lot: money for performing, increased visibility and status, and a chance to plug Black Panther and its soundtrack, which he was paid to curate. And perform in, at least twice: Along with the SZA-featuring ÔÇ£All the Stars,ÔÇØ the Black Panther soundtrack, judging by the trailer broadcast immediately after the concert, is set to include a track with Kendrick and Vince Staples.

Together with his parent corporation TDE (given a notable shout-out at concertÔÇÖs end), the artist always operates in the service of a long-term plan, and always does so successfully. The idea that he would spoil a years-long trajectory of unblemished triumph to take shots at Trump, who lives to be insulted anyway, could never not be dumb. The contrast between the current king of rap and the current president is so dramatic that it speaks for itself. Perhaps what deserves more attention are less evident oppositions: Kendrick wasnÔÇÖt the only young man performing for a national televised audience in Atlanta last night, but unlike the players for the University of Alabama and the University of Georgia, he was the only one actually getting paid for his work.