Rap is broken, and it’s Young Money’s fault. First, Lil Wayne’s champion ’00s mixtape streak powered the New Orleans rapper to the top of hip-hop’s A-list through force of sheer ubiquity. A decade later, Drake figured out that the Recording Industry Association of America counts ten song downloads as a full download of an album and charted dramatically on the 20-song Views and the 24-song More Life. The fallout from Wayne’s realization cannot be understated: Free music is the de facto pathway to rap stardom now. The changes Drake’s moves kicked up in their wake are only just now coming into focus. Mike WiLL Made It has announced that the next Rae Sremmurd project is a triple album comprising a solo apiece from brothers Swae Lee and Slim Jxmmi and a full album from the group. The last two Srem projects were a svelte 11 tracks apiece. The Migos’ new album Culture II is about as long as Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. Wayne, not to be upstaged, released Dedication 6, the latest entry in his flagship mixtape series, in two installments clocking in at a combined two and a half hours. These developments feel retrograde, like tech informing culture when it should be the other way around.

This happened once before, and it didn’t end well. In the late ’90s stretch after 2pac’s and Biggie’s seminal double albums All Eyez on Me and Life After Death, mainstream rappers started making single albums as long as the compact discs of the era could hold, sometimes landing mere seconds shy of the 74- and later 80-minute caps, and double albums as long as motion pictures. Not even geniuses were infallible at such a scale; the period is something of a critical nadir for commercial rap. For every masterstroke like Outkast’s Aquemini, there are scores of promising if frustratingly overlong pieces like Wu-Tang Clan’s Forever, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony’s The Art of War, and Method Man’s Tical 2000: Judgment Day. The bloat served neither artists nor fans, and thankfully everyone slowly came to their senses.

The return of extra-long rap albums seems more dubious now because there are fewer incentives to edit track lists than ever before. In 1998, word got out about your album being shaky, and sales could suffer. In 2018, rap is being consumed in large part via streaming services, where shelling out cash first isn’t a barrier to access for music. Billboard’s decision to bake streaming numbers into its charts and gold/platinum certifications and shift the metric for success away from the old “who bought it” framework to a more SoundCloud-era–sensitive “who’s listening to it” model was great for rap at first. Figuring out that the hip-hop audience ditched buying hard copies for streaming services helped restore rap singles to the top of the charts. It’s hard to imagine Rae Sremmurd, Drake, and the Migos getting their first Hot 100 No. 1’s as lead artists without a chart that tracked the artists’ appeal across platforms. But now that cross-platform play counts are more crucial to an album’s success than hard sales, rappers are working at ways to artificially boost those numbers.

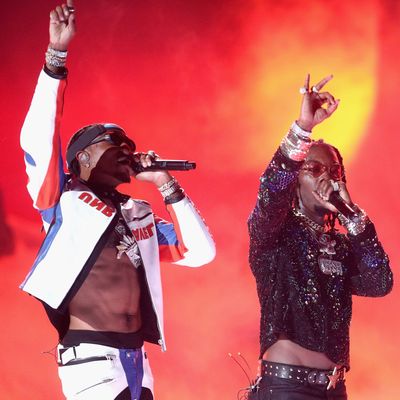

Culture II by the Georgia rap trio Migos feels like the first deliberate artifact of Billboard chart gamesmanship. (Critics and columnists said this about Drake’s Views because it tacked “Hotline Bling” on at the end, but it would’ve been more scandalous if the Toronto rapper didn’t include the hit single with the studio album.) It runs just about double the length of the original Culture, and as sequels go, it’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. The leanness of the original was the source of its power, but the follow-up bogs itself down in unnecessary flourishes. The songs aren’t bad, but they take too long to start really cooking, and nearly every one of them overstays its welcome. Verses are big heaping 12- and 16-bar odysseys (except the times where they skimp and give underrated group member Takeoff just eight). Choruses run as long as some of the verses ought to. Everyone gets a turn, and the chorus plays again at the end. By the time Quavo, Takeoff, Offset, and a guest have taken the mic, the song feels beaten half to death.

It feels like the trio tried to clone the success of “Bad and Boujee,” the nearly-six-minute smash whose running gag was that no one ever listens to the whole thing, instead of working out that Culture was an achievement because it whittled the forbidding heft of the group’s mixtapes down to a more accessible size. Culture II doesn’t have much in the way of killer singles, but it’s packed with memorable performances, like Offset’s run on “Narcos”; the Pharrell collaboration “Stir Fry,” which lifts the group out of its booming trap comfort zone and drops a funky drum break they absolutely crush; or the Takeoff vehicle “Too Much Jewelry,” which gives the least-heard Migo a 20-bar spotlight before collapsing into a delirious talk-box meltdown from Quavo. Double albums are about expanding, not serving up twice as much of the old stuff, and it would’ve been nice to see the Migos use these 105 minutes to get weird instead of slipping into well-rehearsed routines. Culture II will top the charts because it was engineered to, but it feels like watching gifted athletes doing warm-ups instead of dominating in a game.

Now, warm-ups can impress if a player’s in peak form. Lil Wayne hasn’t tried his hand at a proper studio album in a few years now, thanks to label troubles it seems like we’ll never fully understand. He keeps his buzz warm by attacking the popular beats of the day in his mixtapes. This has been his game since the Drought days at least, where one of his screwball freestyles stood a strong chance of becoming the definitive version of your hit single, though no one would argue that he’s as sharp now as he was ten years ago. Dedication 6 and Dedication 6: Reloaded look to change that. The tandem mixtapes are packed to the brim with breakneck rhymes and crackpot lines. “Bank Account” plays fast and loose with Atlanta rap star 21 Savage’s single of the same title, making death-defying word tricks seem easy: “I just popped a Perc / Another for dessert / I washed it down with syrup / I just left planet Earth.” “For Nothing,” the lead track on Reloaded, rhymes “methadone,” “megaphone,” and “leprechaun” in one stretch and “Babylon,” “Tylenol,” and “volleyball” in another. Like the Migos album, these tapes are better enjoyed as flurries of punch lines the listener can drop in and out of than suffered through in full.

Lil Wayne’s attack on these freestyles might come from the same show-and-prove ethos as the Migos, but he’s playing a drastically different game. He’s trying to let everyone know he’s great without exactly selling them anything. His unreleased Tha Carter V album is modern rap’s Schrӧdinger’s cat: The prospect of it being great lingers as long as we can’t hear it. Wayne is trying to succeed as a mainstream rap star almost wholly outside of the parade of studio albums that help power that ecosystem, releasing mixtapes that can’t be monetized on streaming services because they’re full of studious replicas of beats from other people’s songs. In 2007, this was a successful tactic to drum up support for Tha Carter 3, which sold a million copies in its first week. Is he at it again now with Dedication 6 and Dedication 6: Reloaded, the single largest dump of free Lil Wayne music since the Bush administration? It’s hard to tell if reminding audiences that Wayne is a king in exile is Dedication 6’s entire game, or if it’s a setup for a bigger move down the line, but if you dodge the bounty of guest verses from Young Money benchwarmers, you get a snapshot of a veteran catching a third wind and pulverizing a training montage.

The Migos releasing 24 songs to Apple, Tidal, and Spotify, in hopes that twice as many songs will yield twice as many plays is proof that rappers are savvy capitalists. The group ought to have put the work into an album that was half as long and twice as strong, but it serves a chart system that incentivizes high play counts, proving that dumb hacks like this one almost always work. Culture II is the full realization of the “playlist” marketing Drake tried out on More Life. It’s an album in name only; the sequencing doesn’t feel visionary. It’s a data dump. They’re doing with albums what Lil Wayne does with freestyles: scattering their wares and trusting their audiences to snatch everything up. As much as these two- and three-hour projects seem to run perfectly counter to rap fans’ current listening and purchasing habits — Billboard’s year-end rap albums chart from last year is full of 45–55 minute wonders like Big Sean’s I Decided, J. Cole’s 4 Your Eyez Only, Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN., and Post Malone’s Stoney — they could still force irreparable changes to the shapes of rap albums and mixtapes as they exist now. That kind of shift in the culture doesn’t seem worth whatever thousands of YouTube and Apple Music streams these artists stand to earn from it. What happened to quality control?

*A version of this article appears in the February 5, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.