As much as I dislike the automatic applause given to celebrities when they make their first Broadway entrances, the cheers that greet John Lithgow ÔÇö all six-feet-four of him ÔÇö as he lopes onto the stage of the American Airlines Theatre are nothing if not earned. Is there an American actor with a career as wide-ranging, as simultaneously illustrious and eccentric, as LithgowÔÇÖs? The 72-year-old showman has won, among other accolades, two Tonys, six Emmys, two Golden Globes ÔÇö┬áeven four Grammys for his albums of stories and song for kids. HeÔÇÖs written childrenÔÇÖs books (with irresistible titles like Marsupial Sue and The Remarkable Farkle McBride). HeÔÇÖs been nominated for an Oscar twice ÔÇö back-to-back for The World According to Garp and Terms of Endearment in 1983 and 1984. HeÔÇÖs played alien professors (three of those Emmys were for his performance as Dick Solomon on NBCÔÇÖs 3rd Rock From the Sun), diminutive fairy-tale dictators, an elephant nurse called Mabel Buntz in his own adaptation of Camille Saint-Sa├½nsÔÇÖ Carnival of the Animals (in which he performed with the New York City and Houston ballets), and roles as weighty as King Lear and Sir Winston Churchill. That last masterful performance on NetflixÔÇÖs The Crown earned him his most recent Emmy ÔÇö not to mention the undying respect of all us Anglophiles who thought weÔÇÖd never see an American actor play an Englishman as effortlessly and impressively as they seem to play us all the time.

Now this rangy Renaissance man is returning to his theatrical roots in an endearing, straightforward show called, unfussily, John Lithgow: Stories by Heart. ItÔÇÖs a conversational celebration of good tales told well and a touching tribute to his parents, which Lithgow in fact premiered in 2008, four years after the death of his father, as a two-evening Off Broadway affair at Lincoln Center. In the decade since, heÔÇÖs toured it around the country, condensed it into a single two-hour performance, and switched A-list directors. Jack OÔÇÖBrien helmed the showÔÇÖs 2008 premiere, and this time around Lithgow is collaborating with Daniel Sullivan, for whom he played Lear at Shakespeare in the Park in 2014.

I admit I approached Stories by Heart with a touch of skepticism. Famous people talking about themselves in Broadway solo turns isnt exactly my thing, and the shows aura hinted at cozy nostalgia, as if crafted for the Sunday-matinee crowd. (Actually my Sunday-matinee crowd, through no fault of Lithgows, seemed a little cranky. After his second affectionate dig at the midwestern state where he spent a large part of his youth, the woman in front of me raised her hands in frustration and audibly huffed, Whats wrong with Ohio?!) But in the end, I found myself smiling. Yes, theres a healthy helping of nostalgia in there, but Stories by Heart is full of smart, good-natured charm. Its like listening to the reminiscences of a favorite uncle for a couple of hours  If your uncle happens to be a Harvard-educated, monstrously well read raconteur with a brilliant gift for mimicry and a love for literature fills his whole frame with energetic, childlike joy.

Here, that literature is, specifically, two short stories, which Lithgow delivers in their entirety over the course of his show ÔÇö ÔÇ£one in Act One, and one in Act TwoÔÇØ he tells us helpfully within his first two minutes on stage. (ThereÔÇÖs an old adage about ShakespeareÔÇÖs storytelling: He tells you what heÔÇÖs going to do, then he does it, then he tells you what he just did. Lithgow learned from the best.) The stories themselves are, excitingly, not what you might expect. ThereÔÇÖs no Edgar Allan Poe or O. Henry on tap. Instead, Lithgow treats us first to ÔÇ£The HaircutÔÇØ (ÔÇ£a deliciously nasty little story,ÔÇØ he editorializes with glee, ÔÇ£by a gin-swilling cynic named Ring LardnerÔÇØ) and then to the utterly delightful flight of foppery, P. G. WodehouseÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Uncle Fred Flits By.ÔÇØ

In pairing an increasingly creepy monologue of midwestern provincialism (that evolves into ÔÇ£a gruesome tale of adultery, misogyny, and murderÔÇØ) with a farcical, more-British-than-crumpets-and-corgis tour de force by the inimitable creator of Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, Lithgow has picked material that undeniably showcases his virtuosity. His accents are impeccable, his impressions sidesplittingly absurd, and his long-limbed physicality both playful and precise. As he performs ÔÇ£The HaircutÔÇØ ÔÇö a story written entirely in the voice of a chatty barber ÔÇö he gives one to an imaginary customer, miming every snip of the scissors and flick of the razor with a casual, vivid specificity. And in ÔÇ£Uncle Fred Flits By,ÔÇØ he conjures over ten characters ÔÇö from a blustering, Lady BracknellÔÇôesque matron, to a hapless young blighter known (in high Wodehouse fashion) as the ÔÇ£Pink Chap,ÔÇØ to a frankly unforgettable parrot, to the rip-roaring, incorrigible schemer of the storyÔÇÖs title.

Both stories are a treat, but the Lardner is really only a warm-up. ÔÇ£Uncle FredÔÇØ is the showÔÇÖs real treasure and, itÔÇÖs clear, LithgowÔÇÖs real joy. It works so well not only because itÔÇÖs hilarious, not only because it allows Lithgow (quite justifiably and delightfully) to show off, but because itÔÇÖs a story about a storyteller. WodehouseÔÇÖs Uncle Fred is a wily old fabulist ÔÇö a whirlwind who blows into London to upend the life of his dippy, easily overwhelmed nephew Pongo by dragging him off on a variety of madcap adventures. He conjures, he improvises, he pretends ÔÇö and he changes the world by the sheer force of his uncontrollable, loopy imagination. As he and Pongo leave the dingy suburb of London in which Uncle Fred has just assumed the identity of a stranger and managed to arrange a happy marriage for that strangerÔÇÖs niece against the wishes of her priggish parents, the old man philosophizes contentedly to his shell-shocked nephew: ÔÇ£I look about me, even in a foul hole like Mitching Hill, and I ask myself ÔÇö How can I leave this foul hole a better and happier foul hole than I found it?ÔÇØ

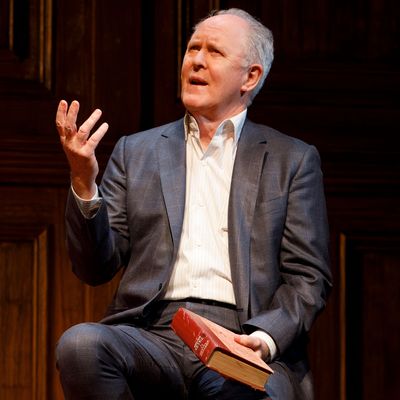

Uncle Fred is an alter ego for Lithgow himself, but also for his father, whose presence fills every corner of Stories by Heart. ÔÇ£Arthur Lithgow,ÔÇØ says his son near the showÔÇÖs beginning, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs one of the bright little pleasures of my life, speaking his name out loud on a Broadway stage.ÔÇØ LithgowÔÇÖs show isnÔÇÖt simply a showcase ÔÇö itÔÇÖs also a eulogy. The stories he chooses come from a fat old volume called Tellers of Tales, a 1939 anthology from which Arthur Lithgow used to read aloud to his four children. Now, his son carries that very same book ÔÇö dog-eared and held together with red duct tape ÔÇö onto the stage with him. ItÔÇÖs a talisman, a piece of Arthur and the source of his sonÔÇÖs life pursuit ÔÇö his true inheritance.

Lithgow speaks of his father with humor and deep love  this thoughtful, caring, meticulous, literate, inventive, handy  and just that little bit wrongheaded man who went from an impoverished childhood in Melrose, Massachusetts, to running the McCarter Theatre and founding several regional Shakespeare festivals. A devotee of the Bard and a producer, director, and actor whose exuberant flamboyance on stage seems to have been genetic, Arthur Lithgow laid the groundwork for his sons life as an artist. And, crucially, so did his wife Sarah Jane, a retired actress and the cheerful, unflappable road manager of the Lithgow familys many relocations and shoestring creative endeavors. Though he never embodies them like Uncle Fred, or Pongo, or Lardners sinister barber with his twitching wrists and wheezing, high-pitched laugh, Lithgow quietly makes his parents the stars of his show. Stories by Heart is about them and for them, as much as its for us.

Despite LithgowÔÇÖs tendency to wax Hallmark card-ish when heÔÇÖs talking about his stories rather than telling them, heÔÇÖs a sensitive enough performer to know when to move on from the personal ÔÇö to feel when his audience needs a laugh and a lift. And when he dives into the words and worlds of Lardner and Wodehouse, Stories by Heart is pure entertainment of the most ancient and appealing kind. In his current sojourn in New York City, Lithgow seems to have taken the words of the immortal Uncle Fred as his touchstone: ÔÇ£On these visits of mine to the metropolis, my boy, I make it my aim, if possible, to spread sweetness and light.ÔÇØ