In the searingly honest, empathetic documentary images of self-described ÔÇ£artist, curator, educator, and photographerÔÇØ LaToya Ruby Frazier, I see the rotten social malignancy that perpetuates entrenched racial discrimination that is deeply inscribed into law, lending, and health-care policies.

I also see obdurate white tribalism, the 55 percent of all white people and 75 percent of all Republicans who think that racial discrimination persists  but that its against white people.

I look at FrazierÔÇÖs beautiful activist art ÔÇö depictions of people with the courage and strength to live life amid Trumpian statecraft and everything that made it possible and consistent with our often-airbrushed history ÔÇö and I behold an aesthetic passionate enough to possibly jar the art world from its ten-year fixation on insular formalist photography-about-photography. The films, texts, and photographs of this 2015 MacArthur ÔÇ£geniusÔÇØ give us one of the strongest artists to emerge in this country this century ÔÇö a 36-year-old oracle calling for a new engaged ÔÇ£movement in photographyÔÇØ that bears witness to our state-sanctioned economic racism and environmental horrors.

What do FrazierÔÇÖs photographs actually document? Everything.

The entire postwar American Dream stacked against American blacks. It begins with the dream of owning a home and blacks who could not get loans from banks or government agencies because they already lived in poor neighborhoods, or who were redlined in similar ways so that they paid more for less where they already lived, while getting fewer services, bad schools, lesser health care. TrumpÔÇÖs own father was found guilty of this. Even NixonÔÇÖs Housing Secretary said that federal housing policies had drawn ÔÇ£a white noose around Black cities.ÔÇØ Then Nixon fired him. It meant the government built 17,500 homes in the much-touted ideal town of Levittown, Pennsylvania, and not one of those homes was sold to a black person. Today less than one percent of LevittownÔÇÖs population is black. Racism in policy runs deep, with costs that last long even when the policy ends.

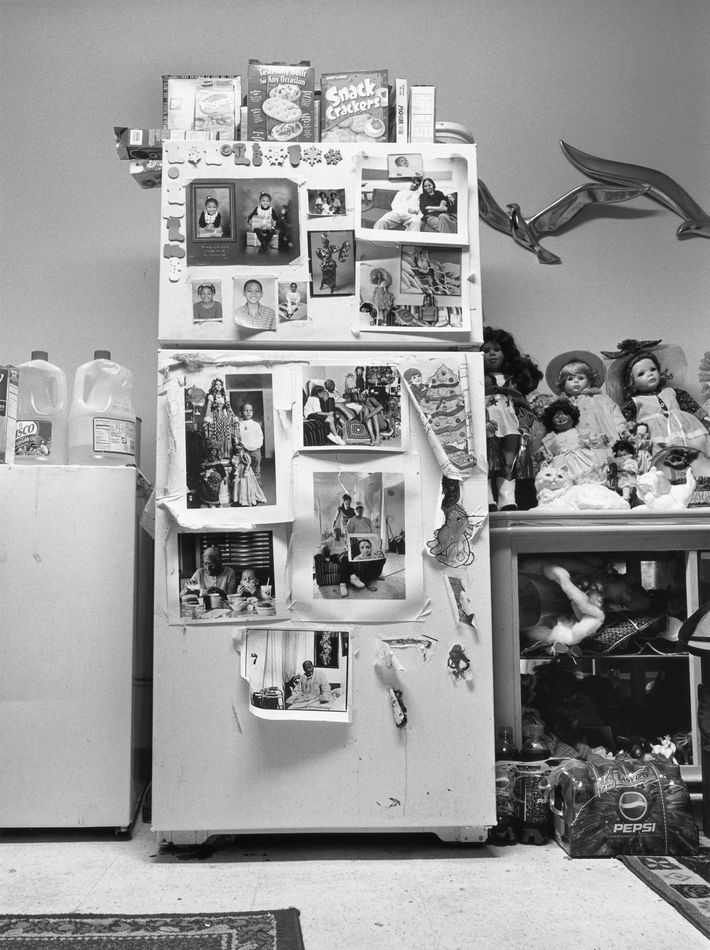

In her first-ever New York gallery solo show, at Gavin BrownÔÇÖs Enterprise, Frazier presents three trenchant bodies of work. FrazierÔÇÖs aesthetic is to get very close to her subjects without ever being predatory or voyeuristic. She shares intimate moments, allows her collaborators to set up photos, record their voices and poetry, and to document their own family histories. Her images are a shadowy, stark black-and-white that conjures the tonal grounds and preternatural observational powers of Rembrandt and Goya.

Many of her pictures are accompanied by text written in the subjectÔÇÖs words. Elsewhere Frazier provides health statistics, legal proceedings, corporate records. FrazierÔÇÖs is a world on the edge, pushed to the brink of extinction. But this is not just ruin porn, or just another photographer visiting and recording nodes of poverty from a privileged position. Frazier has talked about imagining what might have happened had Dorothea Lange allowed Florence Thompson ÔÇö the nameless ÔÇ£migrant motherÔÇØ in her iconic 1936 image of poverty in America ÔÇö to photograph herself, her family, tell her own story. ThatÔÇÖs a radical leap. And itÔÇÖs what Frazier has undertaken, drawing in her subjects as collaborators. Frazier starts to see the world through the eyes of others ÔÇö channeling their dreams, melancholies, hells, joys, and accesses their inner visions.

Flint Is Family was made between 2016 and 2017. It is a giant series that explores the effects of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan ÔÇö a majority-black city. We are given micro and macro views of FlintÔÇÖs environmental catastrophe, scenes of factories, decrepit streets. She zeroes in especially on three generations of Cobb family women. Grandmother Renee, mother Shea, and her daughter Zion. Here we see the firsthand effects of how state-supported ecological disaster leads to businesses and jobs leaving, the breakdown of social structures, and lack of health care that means anyone unable to escape must fend for themselves in a situation that is none of their making.

Frazier uses her camera as a weapon that lets us see the two-tiered Jim Crow laws of racial environmentalism where cities like Flint are made to become blacker and poorer. It is impossible to imagine a systemic 30-year environmental disaster unfolding this unchecked and unaided in Manhattan or Arlington, Virginia. She records how Flint residents still pay some of the highest water bills in the country while their local Nestle factory is allowed to pump 400 gallons per minute of pure Lake Michigan water for free. In an 11-minute video, Shea Cobb calls this what it is, murder by the state ÔÇö whereby the environment leads to self-destruction, hollowed-out bodies, and Flint as a modern plantation where workers are under assault and seen as ÔÇ£bottom-feeders.ÔÇØ

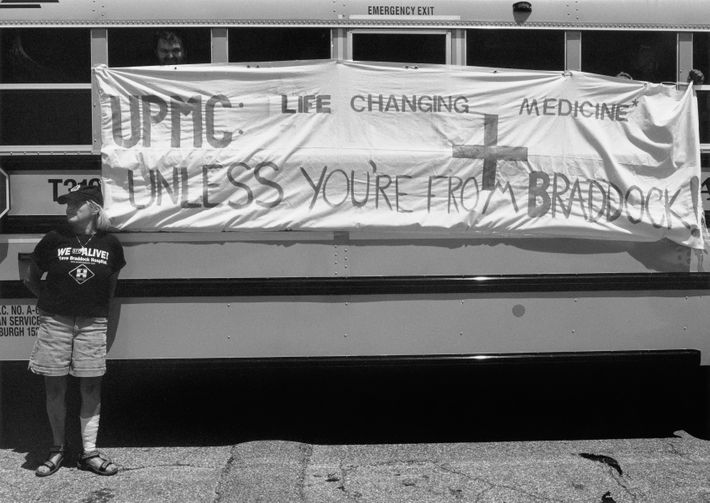

Next is The Notion of Family, begun when Frazier was 16 and started documenting herself, her family, and her surroundings. (A teacher seeing her first photo told the teenager that she had a destiny to work with the camera.) Notion is already a landmark of American photography ÔÇö a new American Disasters of War. We see her hometown Braddock, Pennsylvania, nine miles from Pittsburgh on the banks of the great Monongahela River, home of Andrew CarnegieÔÇÖs first steel mill, the famous Edgar Thomson Works, in operation since 1875. The pictures are raw, beautiful, intense, subtle, prophetic. She focuses on three generations of Frazier women: herself, her mother, Cynthia, and her late grandmother, Ruby. In Notion genres collapse. It is family portrait, autobiography, case study, manifesto, indictment, and howl. It is a picture of 30 years of official negligence and deindustrialization that have brought about the near annihilation of the black working class.

ItÔÇÖs no coincidence that Braddock, like Flint, is a majority-black city. Companies have been cited for chemical emissions of benzene, mercury, chloroform, lead, and tetrachloroethylene ÔÇö a colorless liquid now found in BraddockÔÇÖs water and which brings risks of cancer and immune-related diseases. Here is the human cost of systemic negligence, redlining, and other malevolent policy.

In another group of pictures we witness the death of FrazierÔÇÖs grandmother from pancreatic cancer. Next we see her motherÔÇÖs terrible back-length scar from spinal surgery. Frazier calls her ÔÇ£a prisoner in her own home.ÔÇØ Cynthia, a nurseÔÇÖs aide, lives two blocks from BraddockÔÇÖs former hospital (now torn down). Yet after she collapsed from a series of maladies last year it took over three hours for help to arrive and then get her into intensive care. Here she was examined and told to go home because she had no chance of survival.

ThatÔÇÖs when Frazier contacted Dr. Esa Davis, a doctor of color from Pittsburgh who knew of FrazierÔÇÖs work. Davis soon arrived and, working with Frazier, prescribed treatment saying that her mother must stay in the hospital. This was done against the wishes of the white doctor. Frazier, who had permission to do so, stood vigil over her mother to make sure she wasnÔÇÖt sent home to die or be neglected again. ThatÔÇÖs health care in much of America. So is this: A white physician then falsely accused Frazier of ÔÇ£laying hands on himÔÇØ and security and police arrived and ushered her out of the hospital. Fortunately, ÔÇ£Dr. EsaÔÇØ stepped in again and saw to it that her mother wasnÔÇÖt sent home. Last week, I saw Cynthia looking great and doing well speaking on a panel at the gallery about her life and her daughterÔÇÖs work.

Frazier pictures a not-so-secret but almost ignored war going on in America against the black working class. Frazier depicts her grandmothers step-father in his coffin. She says he worked hard labor in high-temperatures tearing down and rebuilding furnaces, cleaning up spilt metal and slag  his labor-consumed body discarded and thrown away. After this, see the topless self-portrait of the artist seated on a bed, Self-Portrait (Lupus Attack). Frazier eyes us directly in this picture of a person paying the price of her mind, body, and energy in this undeclared war.

Meanwhile, this war has been ramped up. Under Ben Carson, TrumpÔÇÖs head of public housing, the agency has already delayed measures to strengthen civil-rights-era requirements for local governments to take active steps to undo racial segregation. Instead, it is rolling back regulations that Obama had put in place to undo systemic racism. Carson says of the old laws, ÔÇ£The people who put all these programs in place meant well ÔǪ and had no intention of entrapping peopleÔÇØ ÔÇö and then calls it by a nativist name: ÔÇ£social engineering.ÔÇØ Juli├ín Castro, previous HUD Secretary, sighs, saying that ÔÇ£benign neglect is the best way to describe it right now.ÔÇØ And housing, of course, is just the start.

Frazier somehow even captures these unraveling catastrophes in images of local citizens standing up for their rights, demanding clean water, access to health care, the right to live dignified lives. What gives these pictures resonance is that theyÔÇÖre from 2016. Preelection. We see groups peacefully holding signs outside factories, hospitals, and at a local Flint high school awaiting the arrival of then-President Obama ÔÇö who drank Flint water in solidarity.

These pictures speak volumes to our current situation. As horrible, complex, and as frustrating as these situations are, we see that protests like these, back then, at least made America look at the problem, notice it. Or so we hoped. Back in 2016 it almost felt like with the Black Lives Matter movement that one day soon black lives might actually start to matter ÔÇö that bodies like these, in Flint, Braddock, and 10,000 other American towns and cities, would not continue to be ÔÇ£discarded and thrown away.ÔÇØ But then whites in every demographic category voted Trump president and a Republican Party ÔÇö a de facto white peopleÔÇÖs party ÔÇö only intensified its take-back-our-nation last stand.