No one in comics has had a career as unpredictable as Rick Veitch’s. In his nearly 50 years in the business, the 66-year-old writer/artist has put out incredible work across a dizzying array of genres. He’s done perverse underground comix like his self-published Two-Fisted Zombies. He’s done straightforward superhero fare like Aquaman. He’s done avant-garde fantasy like Swamp Thing (a series for which he crafted a story in which the title character would have met Jesus Christ, only to have it be pulled due to sensitivity concerns). He’s done abrasive satire like the War on Terror–lampooning Army@Love. He’s done trippy dream-journal comics like Roarin’ Rick’s Rare Bit Fiends. He’s done The Big Lie, a comic positing that the destruction of the World Trade Center on 9/11 was an inside job.

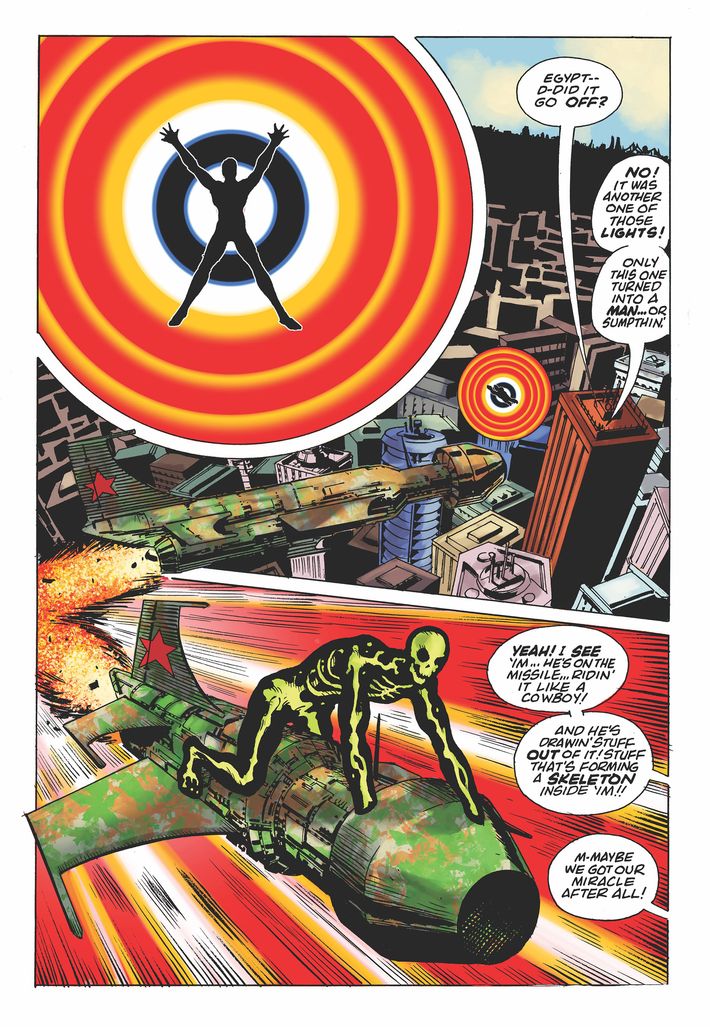

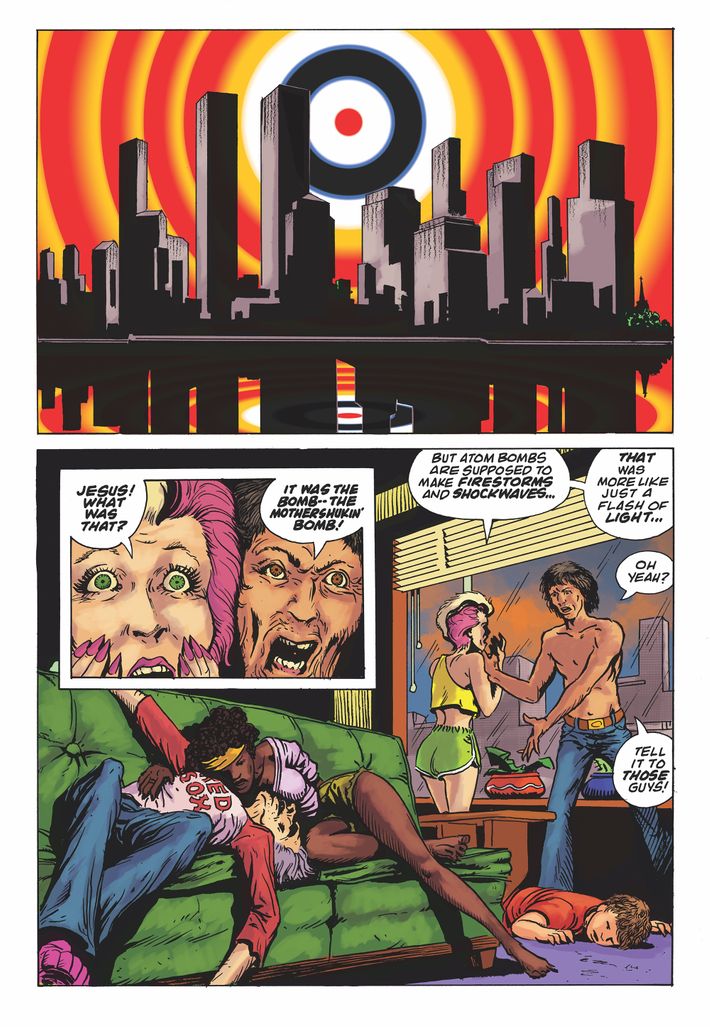

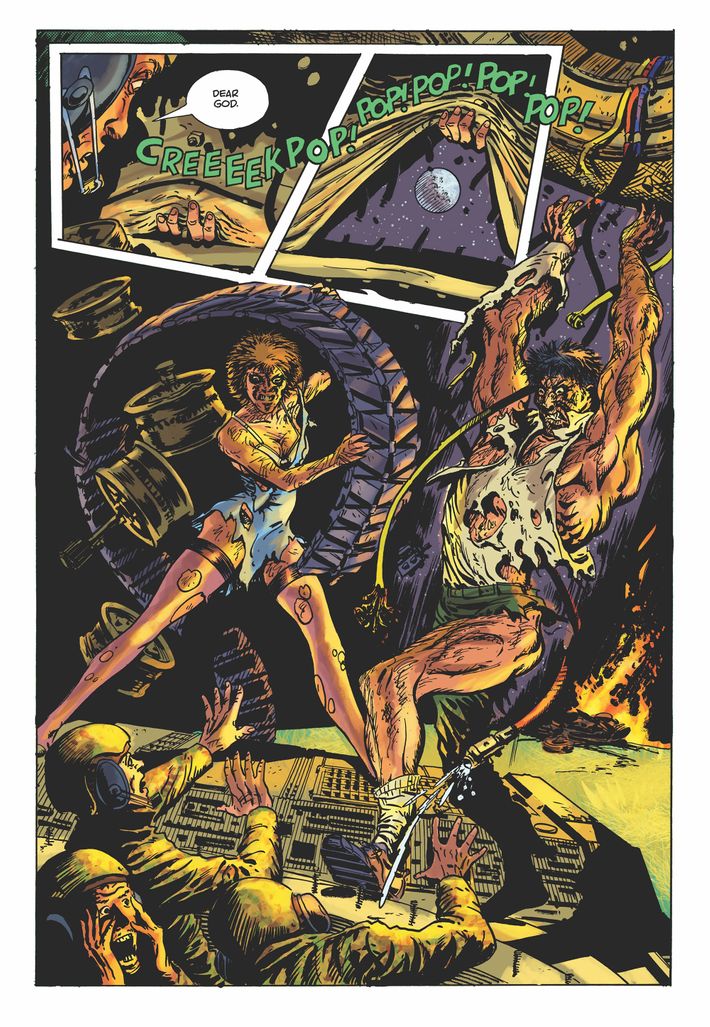

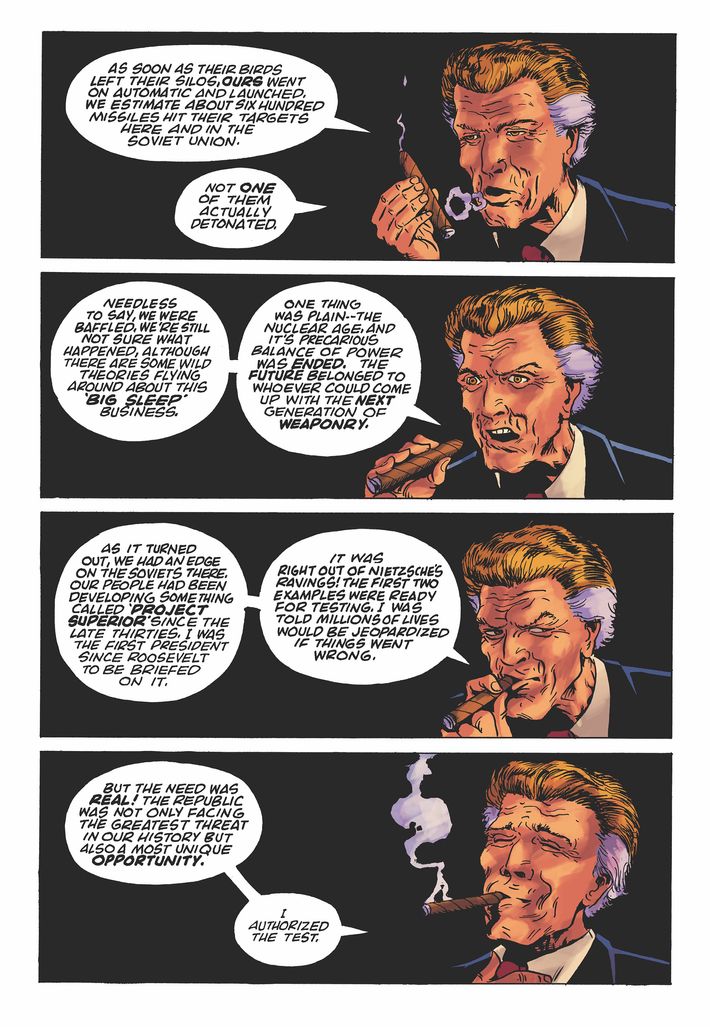

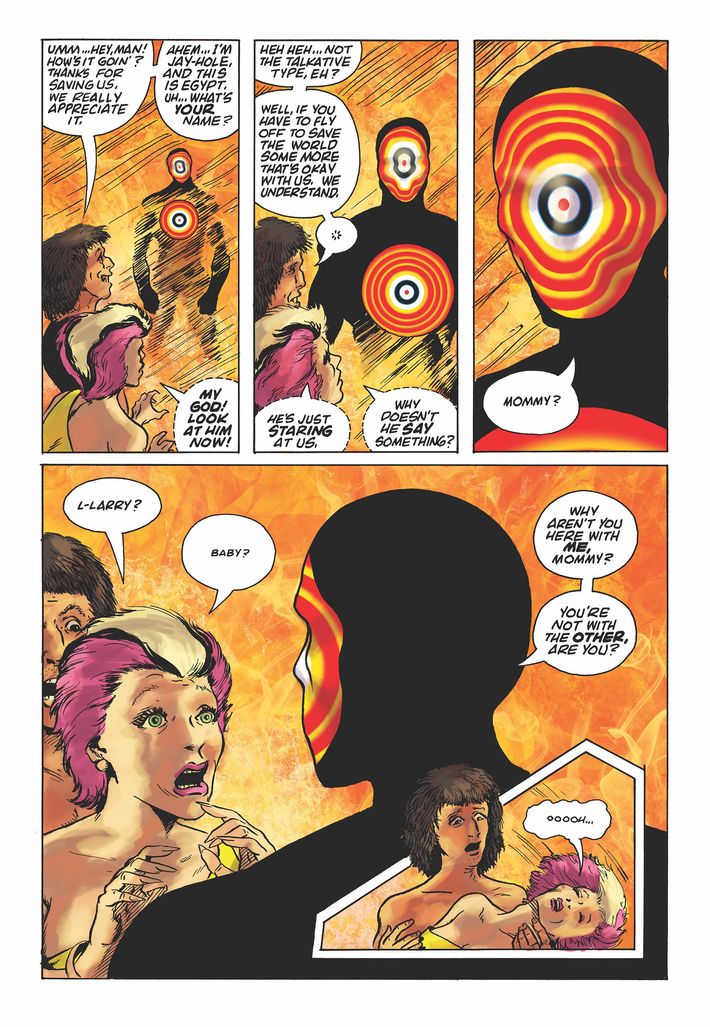

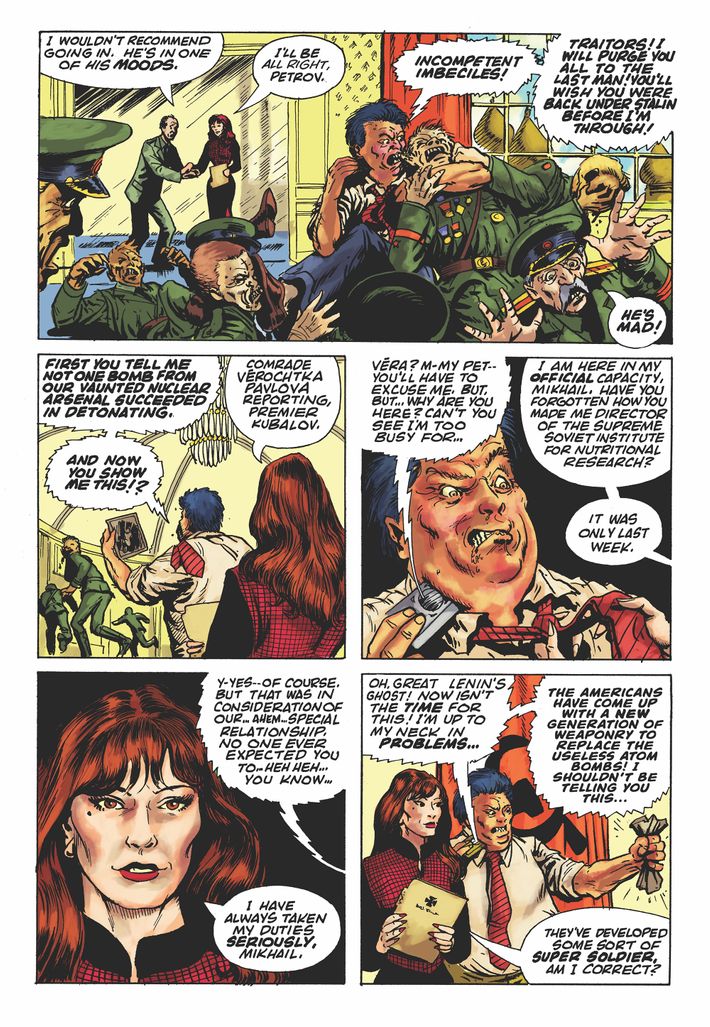

Perhaps most notably, he’s put out a number of comics breaking down the very notion of the superhero. There’s Brat Pack, a filthy story about teen sidekicks gone wrong and the abusive heroes who watch over them (including one particularly repugnant gay stereotype / Batman stand-in named the Mink). There’s The Maximortal, which showed a murderous Superman analogue while lambasting DC Comics for the ways they cheated Superman’s creators. And then there’s The One. Initially released by Marvel’s creator-owned Epic imprint in the mid-1980s, it depicted a world in which the U.S. and Russia are on the brink of mutually assured destruction when a mind-bending superbeing called the One arrives and saves us all, then expands our consciousnesses to a new state of existence.

The One was part of a generation of deconstructionist superhero sagas, including Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins’s Watchmen and Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. However, The One has fallen in and out of print over the years and has never been much more than an impassioned whisper among fans in the know. Now, it’s finally seeing a deluxe rerelease at the hands of publisher IDW, with the first issue hitting stands today. We caught up with Veitch to talk about the fascist underpinnings of the superhero archetype, whether The Walking Dead ripped him off, and his suspicions about 9/11.

What were the origins of The One?

Well, it’s a little bit complex. I first started conceiving of it in the early ’80s: ’83, ’84. On the comic-book end, a lot of us had the sense that there was a lot more that comics could be. The distribution of comics had opened up, and the publishers were opening up with new imprints, like Epic, where a writer/artist like myself could explore things outside of what Marvel wanted to do with superheroes. That was part of it. The other part of it was the political situation at the time, which was freaking everybody out. Reagan had showed up, and the whole era of détente just got pushed aside. He started making a lot of noises about war with the Russians again. It was a scary time, and I was processing all of that, I think, among other things, in the hopes of doing something fresh and new, and pushing the concept of what a superhero could be in a whole new direction.

The villainous character of Itchy Itch clearly demonstrates that you also had a grudge against Richie Rich that you needed to work out somewhere.

I think everything I do is informed by the lifetime of comics that I’ve inhaled. Each comic tends to be kind of cartoony to begin with, and plastic and stretchable in different directions, so it just seemed right to put Richie Rich in there.

If I recall correctly, you had already read some of Alan Moore’s Marvelman at that point, right? It deals with similar concepts.

Right. Marvelman had appeared and had been like a lightning bolt to all of us who were in comics, working in superheroes at the time. [Moore] really was sort of like the Big Bang of the modern superhero — and I should include his artist with him, Garry Leach. They succeeded in — just like the Rolling Stones succeeded in taking old blues music and repackaging it for an American audience, Alan and Garry and the other artists on Marvelman succeeded in doing that. A lot of people recognized it, but didn’t quite know how to make that work. I was probably one of the first, I think, to try to take that inspiration into my own work, and again, try to push the superhero thing in a whole new direction. When I was a kid in art school, at the Kubert School in the ’70s, we would sit around, and we would go, “These superheroes, they’re so infantile. If someone just approached them with the depth of a modern science-fiction novel, like Isaac Asimov or Stanislaw Lem, one of those guys, it could be really amazing.” I think Alan and his partners were the ones that first pulled it off, with Marvelman.

Along those lines, what do you think made the mid-’80s particularly germane for that kind of experimentation? You had all these revisionist or deconstructionist takes on superhero fiction all of a sudden, from Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns to Squadron Supreme and, of course, The One.

Part of it was the business itself, which was rebooting itself. The old method of distributing comics, the mom-and-pop stores, on newsstands, had collapsed. Comics shops were opening up, they were hungry for new material, and the readers were hungry for new ideas. It was like this golden era for creators, where the companies were ready to bring in new, young faces and to put the money up to put together projects that ultimately we owned, which was even better. Not only was I doing superhero comics, but I owned the material moving forward. It was a pretty fantastic thing at the time.

I know The One was part of Marvel’s Epic imprint, where you could get away with more outré stuff than in the main line, but what red lines were laid out for you beforehand?

I guess everybody understood that you couldn’t show actual penetrative sex. But you could talk about sex, and you could have people in bed together. It couldn’t be, like, X-rated, but it could be R-rated, which was fine. When reading The One, you’ll see that we never used the word “fuck.” I did the same thing that Norman Mailer did in The Naked and the Dead, where I created my own fuck word, which is “shuck.” That was a thing which some people didn’t like, I’m afraid.

You start the book out with that article about Marshall McLuhan saying the atom bomb is bringing us together as a species, and I’m curious, how did you come across it?

That was in the New York Times. It was one of those things that hit me like, “Wow, there’s this whole other aspect, you could almost say a spiritual aspect or a psychological aspect, to the modern problem of living with the bomb.” Here was McLuhan’s people talking about it in that way, so I thought, “Let’s explore that. What if this thing does really transform us as a species, what would it be?” I moved in that direction.

Archie Goodwin edited The One, right?

Yeah, Archie. He totally got it. Even though he was an old-schooler, he totally got it. There were certain things, you’d bring the pages in to show him, and he would just be chuckling. I think how it was seen at Marvel … even though it sold really well — I think it sold about 50,000 copies an issue — that wasn’t enough for those guys. They wanted sales in the line of what X-Men was doing at the time, which was like a quarter million. It was seen as, “Run of the mill book, not that great.” I think while a lot of people got the writing of it, I think my black-and-white ink style at the time was a little too crude and greasy for what Marvel Comics likes. What I was hearing from people like [Marvel editor-in-chief Jim] Shooter, was like, “You’ve got to tighten your stuff up, Rick. Maybe we’ll get you working with an inker or something like that, to make it look cleaner.” The One is what it is. It’s like music, you know? I sat down and started working on it, and it just like poured out at a high rate of speed at the time. It stands as it is, I think.

The last time you collected The One, you wrote in the introduction that you were hoping to have a more optimistic introduction with the next printing because the world of the future would be better. I assume you feel your hopes have been scuttled.

Yeah. Gorbachev and those guys, there was going to be glasnost and everything. And, “Hey, maybe we were past this nuclear war thing!” But it’s all back again. Now we’ve got Trump, and he’s threatening the North Koreans, and the North Koreans are threatening us. The specter of nuclear war is once again in our hearts and minds. I’m not sure how many people are taking it seriously, but I kind of do. I have to say that, going back and reworking the whole thing, cleaning up the lettering and scanning it and everything, the zeitgeist that I captured in the ’80s is back with us. That absurdity in politics and international relations, and living under the threat of nuclear warfare, is back with us.

Well, we’re experiencing a resurgence of two things that play into The One: A nuclear threat and a fixation on superheroes. How do you explain the current superhero boom across all media?

Well, you could tie it to a lot of things. One of the things is the rise of nationalism and fascist thought. The superhero is kind of like a fascist art form. He is a fascist fantasy. His roots are in Nietzsche’s superman, which the Nazis used as a mighty propaganda tool back in the day. It breaks my heart that these issues are still being struggled with today. Even more so. On the other hand, we live in an age in which we’re going to be physically transformed. Science and medicine are changing what it means to be physically human. The idea that there might already be or will soon be what people call “trans-human” individuals is a reality, it’s not a fantasy. That’s part of thinking about superheroes and why they’re important now. It’s a way the culture sort of feels its way into its own future. By looking at Green Arrow and Black Widow and those guys, we sort of feel our way into, “What’s going to happen when we’re all super-gymnasts, or can live forever?” The other aspect that I’m perturbed about — and I hope The One can stand against — is the corporate control of superheroes. I think everybody gets the fact that superheroes are a replacement for myths, like Little Red Riding Hood, and the old gods, and stuff like that, but they’re owned by corporations. It’s a subtle way of directing people’s energy and creative flow into these preformed archetypes, if you will. I don’t know if you’ve been to any Comic-Cons lately.

Sure, of course. Every year.

Then you’ve seen in the last few years, that they’ve turned into these cosplay events, where thousands of normal civilians show up dressed in superhero costumes, like to the max. They’ll be like crowding the aisles of these shows. Instead of comics nerds looking for old comics, it’s people sort of strutting around, almost like a festival or Mardi Gras or something. What I don’t like about it is they’re not expressing themselves with images that come from themselves. They are dressing themselves in these prepackaged, corporate archetypes, and I’m not sure where that all goes. I think, as a creator, I want to stand against that. I want to do superheroes that break that open. I like to think that The One, and Brat Pack, and Maximortal, and some of the other ones I’ve done, move in that direction.

I guess the counterargument, when it comes to cosplay — and it’s the same thing with fanfiction and fan art — is it’s people trying to reclaim those things from a corporation. You can take those archetypes and break the rules with them, mess around with them, do your own thing with them, and subvert them. Do you see any validity in that, or do you see cosplay as just being a negative thing?

No, I don’t see it as a negative. I do understand exactly what you’re saying, but I believe in the mentality of like an old European festival, was that people would look into themselves and express something that was in their own hearts, not a prepackaged idea. I think it’s more important, because you’re really living your own dreams, not a dream that’s created for you by someone else, if that makes sense.

You’re also bringing back Brat Pack at IDW. I had never read it until I was getting ready for this piece. I’m curious, is there more that you would want to change in Brat Pack? I know you changed a bunch when you did the last collected edition, all those years ago.

No, I think Brat Pack, for all of its in-your-face rudeness, stands as it is now. The edition that IDW plans to do will have extra material in the back. At the time we did Brat Pack at Tundra, back in ‘91, I produced a lot of marketing art for it. A lot of neat stuff I’ve got stashed away. It should make a really nice hardcover edition.

Did you really get a letter from NAMBLA thanking you for Brat Pack? I heard that somewhere.

Yeah, yeah, it was some guy thinking I was supporting child molesting.

That’s got to be the weirdest fan letter I’ve ever heard a comics creator getting.

Yeah, tell me about it. It made me wonder what I was doing, too. I thought I was just being a wise guy, but if people take it at that face value, you’ve got to wonder what’s going on out there.

If you had the idea for Brat Pack and started it today, do you think it would be the same work or do you think you would do it differently?

I probably would handle Mink differently, because the Mink is really offensive. I get it. I know that. I’ve optioned the movie rights a couple of times on it, and I’ve talked with producers and writers about how to do it. There’s a lot of different ideas how to make the Mink more of a positive gay character, rather than just a child-abuse thing. At the same time, that absurd vision is part of what Batman and Robin are. Society has always sort of suspected that that’s what was going on between Batman and Robin. Somehow you’ve got to bring that out and use it, especially with a book like Brat Pack, where you’re essentially stabbing all the sacred cows that make corporate comics work. You’ve got to look that thing right in the face, as ugly a stereotype as it is for some people.

The One featured a number of backup comic strips with crudely drawn characters in strange situations, called “Puzz Fundles.” Will they be reprinted, too?

Absolutely. The One could not exist without “Puzz Fundles.”

The pseudonym you used for the “Puzz Fundles” strips was “Rick Grimes.” Do you think Robert Kirkman ripped that name off for the main character of The Walking Dead?

Well, you know, I’ve always wondered, because Kirkman would have been of the correct age to be a teenager, to have been reading The One. I’ve never run into him. I’d love to ask him that question. If anybody knows, I’d love to hear.

I’ll have to ask him about it sometime. Will we see the fully naked kid at the end of The One, or did that have to get cleaned up?

You know, I’m just doing that issue now. I guess that’s a question I’ll have to ask [IDW editor] Scott [Dunbier]. I hadn’t even thought ahead. Thanks for the warning.

It’s not something you see in your average superhero comic, but I guess that’s true of a lot of the stuff in The One.

Yeah, I was using all these Beatles lyrics, so we had to change those lyrics, so they weren’t quite the Beatles.

Oh really?

Yeah. The things we could get away with in the old days!

Can you give me an example of a fake Beatles lyric?

If you look at the second issue, the original version opens with, “I am he, as you are he, as you are me, and we are all together.” I had to scramble that up in the color version, so it’s like, “We are he, as you are me,” something like that. It’s obvious where it’s from, but without using the exact same phrasing.

Got it, okay. I didn’t do the compare and contrast closely enough.

Hardly anyone notices, except the Beatles’ lawyers.

You did a little bit of work with Image Comics a few years back, with The Big Lie, your 9/11 comic. What were the origins of that?

My friend Tom Yeates and I are liberal progressives. We get on the phone, especially when the Americans went into Iraq, we were just outraged at how this had all developed. Both of us started looking into some of the questions about the 9/11 incident. There’s so many unanswered questions that the Commission had left open, that it was real easy to imagine that maybe this happened and maybe that happened and maybe this happened. Tom connected with this group who are allied with the architects who were trying to get the word out about the nature of the collapse of the Twin Towers. They wanted to do a comic. They put up the money and hired us to do it. We relied on their expertise about which issues that we should focus on, which questions. Then I created a Twilight Zone sort of story that got that information across, so that people would at least ask the question, “Gee, why didn’t they look at this?” I guess going even further back, the roots of it are that I grew up in the ’60s. I remember the Vietnam War and I remember the Pentagon Papers being released, and how it was revealed that we’d all been lied to for years about this thing. I tend to not believe the story that the government gets behind on some of these things. I’m naturally suspicious about it, and the 9/11 collapse of those towers leaves so many questions. I’d love it if they would go back and reinvestigate what happened.

Did you get any backlash from Image or from readers?

The impact was more online. USA Today did an article about it, and Huffington Post picked it up. There were hundreds and hundreds of comments. One of the interesting things is when you read them, you get the sense that some of them are not people, but are bots. This was in 2011, before what we learned in the last election cycle, about how automated bots are being used online to direct opinion. I’m not sure what happened there, but that was my impression reading them, that this wasn’t all people. It was like they were writing from a preordained script or something, rather than their own thoughts.

You didn’t get any heat from families of people who died in the towers or anything like that?

I got a couple emails from people who were kind of angry, but I explained that there were these questions and that the best thing we can do to honor the victims is to find out what the hell really happened and get it out there. That makes sense. Even to a relative of a victim, that makes sense, I think.

Few creators have your range of genre and style. Is writing something like your dream-journal comics a fundamentally different experience from writing, say, Aquaman? Or is it all of a piece?

It’s fundamentally different, in the sense you’ve got clients that you’re working for. In Aquaman’s case, it’s your editor at DC and the publisher at DC. They’ve got a hand in what they want, so you’ve got to work with them and provide what they want. At the same time, I can’t help myself. Pieces of myself end up in there. Symbolism that’s important to me will end up in those things. Aquaman wasn’t a great project for me. I was really sick at the time. One of the reasons I took it was to get health insurance. I’m not really fond of that particular project. I’d like to forget it actually. Like the stuff I’m doing right now with Rare Bit Fiends, it’s like I’m working with my dreams, and trying to explain states of consciousness that a lot of people are vaguely aware that we experience as humans. That’s much more exciting and creatively fulfilling than doing Aquaman is ever going to be.

But the fact remains that you did Aquaman even after your acrimonious falling out with DC over the Jesus issue of Swamp Thing. How did you come back?

What happened was that I was part of the America’s Best Comics line, which Alan Moore founded. That was originally done with Jim Lee’s company, [WildStorm]. Lee sold his company to DC. We found ourselves all of a sudden, like baseball players, we’d been sold to another team or something. Alan felt really bad about it, but he felt like he had to go forward because he had brought all these artists in. We had three months of stuff already finished. I felt bad about it because I really didn’t want to work with them, but they made strong overtures to us and promises to us, about how things would happen. In Alan’s case, I think a lot of those promises got broken. In my case, they were pretty decent to me. They drew me back into the fold. There was discussion over the years of, “Hey, maybe we can do Swamp Thing,” and I think that’s one of the reasons that kept me there, but they were never able to really get that together. Like I say, I got sick and I needed health insurance. I was in my early 50s, and that was a thing that cemented it for me. Now, I live in an age where I can get health insurance through Obamacare, so I’m not chained to any company anymore, which is really great.

Do you think you’d ever go back and do mainstream superhero work again?

It depends on the terms. When I look at what’s coming out, I don’t know if there’s a place for me in there anymore. It’s all cementing into place. It isn’t a plastic medium anymore, if that makes sense. It’s stuck. If a door opened and it allowed me to explore new things, then yeah, I would think of that. I would love it if DC would publish Swamp Thing No. 88 [the Jesus issue] and allow me to finish that whole graphic novel. I mean that would just be awesome.

As much as DC takes risks these days, I don’t think that’s a risk they’d probably take.

It’s cool being the one book that they don’t get published. I’m the guy who did it.

Have you stayed in touch with Alan Moore at all?

Oh yeah, yeah. We talk all the time. It’s been fantastic working with him. It’s been sad seeing some of the shit he’s had to deal with, because of his stardom. He’s a lovely guy. He’s always amazing. I’m quite fortunate to have worked with him.

DC just introduced two America’s Best Comics characters into their mainstream universe: Tom Strong and Promethea. Will yours and Alan’s character, Greyshirt, do that anytime soon? Or is he safe from the corporate clutches?

I don’t think it’s safe. I think all of them might get inhaled, but I have to go back and revisit the contracts and talk to DC’s legal about what it all means. I’m not sure yet. I haven’t really dug into it. I doubt Greyshirt is one of the first ones they want to get in there, because I think Tom Strong and Promethea were the star characters. I hope they don’t, I really do. I think it’s not good, how they have treated Alan and his creations. I wish, especially … Actually, I probably shouldn’t say anything. Other than to say, I wish they’d leave Alan alone and let him be creative.

On a completely different tack, how do you get into dream analysis? I read that you got into it in your 20s — how did that happen?

I was living the wild life of a ’60s teenager and fell into a depression. Out of that depression, I started to have these powerful dreams that were so powerful that I started writing them down. Right at that time, someone gave me a copy of The Portable Jung, which was this big, fat, compendium of Jung’s writings on dreams and mythology. I didn’t quite understand it, but at the same time, as I read it, it was like, “Yeah, this connects, this connects. There’s a way out here, of my depression.” And it worked. It helped me get back on my feet, center myself. So the rest of my life, right up til this morning, I write my dreams down every morning and I think about them during the day. Of course, Rare Bit Fiends became my artistic expression of that, which I think powered the thing up even more, in terms of what it did, how I began to understand myself and how dreams worked. It was a really fantastic experience.

You mentioned in a recent Rare Bit Fiends that you had some commercial success recently, and that you were doing well because of that. What was the commercial success?

I started a company with my partner Steve Conley focusing on educational comics. It’s called Eureka Comics. We’ve had a number of projects at McGraw-Hill. We’re actually using comics to create classroom materials, educational materials. That’s really interesting. I’ve been doing that for about five years now. I just picked up one of those new iPads, which also you can draw on it with a stylus. I try to do one or two panels each evening on a completely separate project. I’ve got one going right now, which is going to be like The Spotted Stone. I’m about 25 panels into it.

Oh, The Spotted Stone — that’s the wordless comic you did, right?

Yeah, I call them “panel-vision comics.” You have a single panel on a page. I just like that whole idea. It forces you to read it visually in a different way than you’re used to, which I think is cool.

What do you think comics as a medium can do that other mediums can’t? What’s special about comics?

Well, they synthesize the mind. That’s why you get a buzz when you read a comic. One side of your brain processes the words, and one side processes the image. In the hands of somebody who really knows what they’re doing, they bring those two things together and you get that frisson in your mind of like, Yeah. Y’know? That I think is the power of the medium, right there. Everything else, any other medium can handle. But the comic has a certain experience that, at its best, no other medium can duplicate.

This interview has been edited and condensed.