As I held Marvel’s just-released Miracleman Book One: A Dream of Flying in my hands a few days ago, my fingers trembled and these thoughts overtook me: Dreams can come true. Art can triumph over bureaucracy. A better world is possible. Such joy might seem like overkill to an outsider — after all, the book is merely a collection of superhero comics published more than 30 years ago. But for comics diehards, its release is nothing short of (forgive the unintentional pun, but no other word seems appropriate) miraculous.

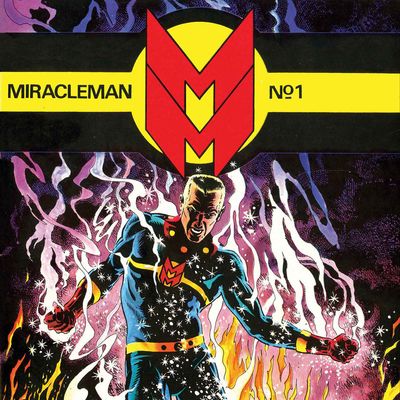

For decades, it was an article of faith that the world would never see a legal reprinting of Miracleman, a seminal British series of the 1980s (it was originally titled Marvelman, but we’ll get to that in a moment). This was an artistic tragedy for a number of reasons. First off, it was one of the earliest superhero works by Alan Moore, the legendary comics writer who would go on to pen opuses like Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell, Batman: The Killing Joke, and many more. Second, it was arguably the ballsiest superhero story ever told when it began publication in 1982 — overflowing with deconstructionist ideas and chilling violence. And, perhaps most tragically, the legal fight over Miracleman showed the world just how petty comics professionals could be.

The ins and outs of the battle over Miracleman are complex and disputed, and I won’t try to recount them all here. (If you want a more complete account, pick up a used copy of George Khoury’s Kimota! The Miracleman Companion or wade through the fan site miraclemen.info.) But the basic outline is a fascinating case-study in how self-defeatingly disorganized the comics world often is.

****

In a way, the character was doomed to legal limbo from the very beginning. After all, he was a semi-legal knockoff created in the wake of an international copyright dispute. In 1954, British comics fans had few great superheroes to call their own. Almost everything worth reading came in the form of imports from the U.S., usually seen in black-and-white anthologies printed on low-grade paper. One especially popular American import was Fawcett’s Captain Marvel, which followed a boy named Billy Batson who, upon uttering the magic word “shazam,” could transform into a super-strong flying wonder.

In 1953, a lawsuit back in the U.S. forced Fawcett to cancel Captain Marvel, leaving its British publishers in the lurch. So, cheap pulp merchants that they were, they created their own English-born ripoff called Marvelman. The similarities were hilariously transparent. Instead of Billy Batson, you had Micky Moran. Instead of shouting “shazam” to transform, he shouted “kimota” (“atomic” pronounced backward, for some reason). Instead of sidekicks Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel, he had Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman. But fans weren’t picky, and Marvelman’s four-color adventures were wildly successful for years. But in the early ‘60s, restrictions on U.S. comics imports eased up and Marvelman simply couldn’t compete with the flood of stories about Superman, Batman, and the like. The comic disappeared in 1963. It seemed Marvelman would never fly again.

Flash forward to 1982, when Britain was experiencing an explosion of ambitious young writers and artists. Comics entrepreneur Dez Skinn — sometimes referred to as the “British Stan Lee” — launched a new monthly anthology series called Warrior. He had a strange idea: Why not bring back Marvelman and give the creative reins to one of the U.K.’s young guns? Why not see what a twisted creative mind could do to a bland 1950s relic?

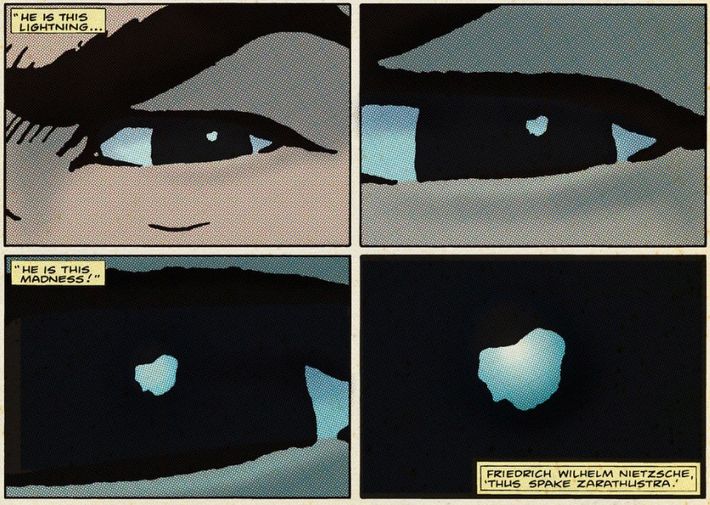

The job fell to 28-year-old Alan Moore, who was far from a household name at the time. What he created was nothing short of revolutionary. Right away in his first few Marvelman stories, Moore introduced three brilliant conceits that have been aped countless times since: What if everything you thought you knew about a famous superhero’s origin story was a lie and the truth was far more unsettling? What would happen if ordinary people in the real world gained superhuman abilities? And why not write a superhero as being truly, unrestrainedly godlike?

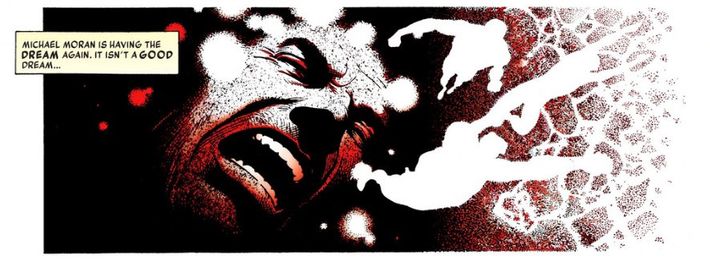

In the collection that just hit shelves, you can find out how Moore and the exceedingly talented artist Garry Leach answered those unprecedented questions. As the story opens, middle-aged freelance photojournalist Mike Moran is down on his luck: aimless, depressed, and poor in Margaret Thatcher’s England. Occasionally he has eerie dreams of high-flying superheroics. Then, while photographing an anti-nuke protest gone awry, Moran accidentally whispers “kimota” and finds himself transformed into the blue-costumed Marvelman. He saves the day and, with near-orgasmic ecstasy, soars out of Earth’s atmosphere while screaming, “I’M MARVELMAN! I’M BACK!!”

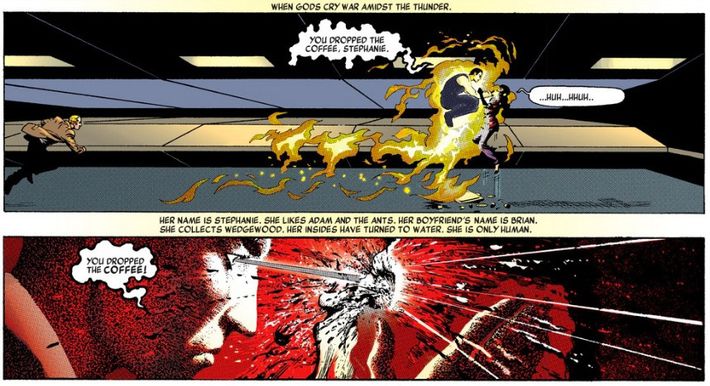

But here is where the tale diverges from a conventionally joyous superhero origin story. Moran reunites with the now-grown Johnny Bates, formerly sidekick Kid Marvelman and now a fabulously wealthy electronics mogul. But Bates has spent the years since Marvelman’s 1963 disappearance honing his superpowers and losing all empathy for the billions of mortals around him. He reveals his powers and goes into battle with Marvelman.

In a series of panels that have lost none of their shock, Bates casually murders his secretary by burning her skull from the inside, then tosses a toddler toward a concrete wall (Marvelman swoops to the rescue, but stutters while telling its mother, “I think I might have broken a couple of his ribs … The speed he was traveling, you see. I couldn’t … uh …”). Moore’s narration prose is overwrought at times, but possesses a goose-bump-inducing grandeur rarely achieved in superhero pulp:

They are titans, and we will never understand the alien inferno that blazes in the furnace of their souls […] We will never know the destiny that howls in their hearts, never know their pain, their love, their almost sexual hatred … and perhaps we will be the less for that.

I’ll stop spoiling the rest of the book, but suffice it to say it only grows more ambitious as we learn tidbits about the mysterious government experiments behind the original Marvelman adventures of the ‘50s and ‘60s, meet a tragic and psychotic quasi-clone of Marvelman (Big Ben, “the man with no time for crime!”), and get a sneak preview of a near-apocalyptic battle that readers wouldn’t see in full until much later. (We also meet a person of color named Mr. Cream whose depiction is, to Moore’s detriment, very racially insensitive. Luckily, Moore’s grown by lengths and miles since he penned these stories.) Moore’s text isn’t as nimble as it would become later in his career, and the brisk pace of the story can be a little hard to follow at times. But overall, it remains a thrilling yarn that leaves you craving the next chapter.

And yet, after reading this synopsis, a reader picking up Miracleman Book One will be profoundly confused about a couple of things: Why the hell is the main character called “Miracleman”? And why the hell is the writer credited as, and I quote, “The Original Writer” and not Alan Moore? Therein lies the backstabbing-filled behind-the-scenes story that so improbably led to Marvel Comics’ publication of this slim, dense volume.

****

Moore’s groundbreaking Marvelman stories continued until 1984, before abruptly stopping on a mouth-watering cliff-hanger. The reasons are shrouded in he-said-she-said bickering. Marvel Comics allegedly pressured Warrior’s publisher to drop the series because it was misleading buyers by using the word “Marvel” in the title. But while that may have been true, in recent years it’s become clear that there were massive conflicts between Moore and Skinn (Moore says he felt the publisher was being financially unfair to Marvelman’s original creator, Mick Anglo).

But the story survived by crossing the pond. In the early ‘90s, a low-rent American publisher called Eclipse bought the rights to the character and started reprinting the Warrior pieces in the U.S.; but to avoid legal problems, they renamed the character and the series Miracleman. And Eclipse didn’t just expose Americans to the existing Moore story arcs — they continued the saga with Moore protégé and budding literary icon Neil Gaiman at the typewriter.

Gaiman’s stories fleshed out the world Moore created in breathtaking ways, but even the godlike Miracleman couldn’t beat back financial reality: The comics industry fell into a massive slump, and Eclipse went out of business in 1994. The epic saga had another abrupt, untimely stop with Miracleman No. 24. The paperback collected editions of the Eclipse issues quickly went out of print. Fans unearthed some unpublished scraps of artwork and text and passed them around surreptitiously for years. In the pre-internet age, there was virtually no way to get your hands on the stories. Miracleman became the most famous comic that nobody could read.

Matters got even worse when the infamous comics writer/artist/entrepreneur Todd McFarlane somehow got involved. He bought Eclipse’s creative assets in 1996 (allegedly for a measly $25,000) and published a 2001 story in his Hellspawn series that featured Mike Moran. Neil Gaiman claimed he had co-ownership of the character and created a legal entity called Marvels and Miracles LLC with the sole goal of sorting out the now insanely complicated copyright tangle. Gaiman even took a job writing a far-fetched miniseries for Marvel Comics just to pay for the legal fees (“To Todd, for making it necessary,” the series’ dedication read). MacFarlane backed down, but the world was no closer to being able to see these incredible stories, much less see them come to a conclusion. Fans were still left in the lurch by catty infighting.

But hope has a way of springing eternal. Out of nowhere, Marvel Comics announced in 2009 that it had purchased the character rights. (This was, of course, ironic, given the disastrous consequences of Marvel’s attack on the character’s name in the ‘80s.) In 2013, Marvel went even further: They announced they were going to reprint all of the existing stories … and let Neil Gaiman finally write and publish the end of the saga. Even longtime skeptics cautiously rejoiced.

And now, every month, you can pick up a new issue of Miracleman on comics stands everywhere. Collected editions, such as A Dream of Flying, will come out every few months. Alan Moore long ago became a hermetic curmudgeon who loathes all attempts to make money off of his work, so he isn’t allowing Marvel to use his name, ergo the bizarre writing credit for “The Original Writer.” (Perhaps someday he’ll adopt an unpronounceable, Prince-esque symbol?) And it would have been nice to see the character name revert to its original state. But hey, let’s not look a gift hero in the mouth.

Stay tuned, readers, because the reissued stories are only going to get better. A Dream of Flying is lovely, but the truly jaw-dropping stuff is just a few months away. You’ll get to see “Scenes From the Nativity,” in which Moran’s wife gives birth to a superpowered infant in an infamously (and, in its way, beautifully) graphic manner. You’ll experience the astounding conclusion of Moore’s run: a city-demolishing fight between Miracleman and Johnny Bates that will turn your stomach and expand your mind, followed by an issue in which Miracleman assumes his rightful role as a god and creates a worldwide quasi-socialist utopia. You’ll delight in Gaiman’s series of short stories about life in that utopia — one of which is a gorgeous little tale narrated by an undead Andy Warhol. You’ll read about modern myths and see better worlds. And soon, God (Miracleman?) willing, you’ll find out how it was all supposed to conclude. Wonders never cease.