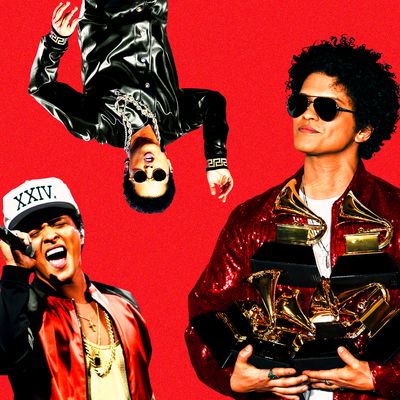

Every so often, the cultural discourse resets itself, and accusations of appropriation are launched (or relaunched) at a different target. Four years ago, the offender was Miley Cyrus; two years ago, it was Macklemore and Iggy Azalea. He wrote a mea culpa about his white privilege, Iggy retreated from rap, and Miley went country. Adding a new wrinkle to the conversation is Bruno Mars, whose unmistakable references to funk, R&B, and New Jack Swing in his art have long sparked whispers of appropriation — and lawsuits over alleged similarities — because he is not black, but owes his success to black music. (Mars’s background includes Filipino, Puerto Rican, Spanish, and Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.) The debate reignited following his six Grammy wins this year — including Album of the Year — when a clip from a YouTube roundtable challenging Mars’s claim to black music went viral on Twitter last week. Writer Seren Sensei argued in the video, “Bruno Mars got that Grammy because white people love him because he’s not black, period. The issue is we want our black culture from non-black bodies, and Bruno Mars is like, ‘I’ll give it to you.’”

But is the issue so black and white? What does appropriation look like when the accused appropriator and those being appropriated are both people of color, but do not share the same racial or ethnic background? Can there be a cultural exchange between two minority cultures that exists without offense? Does “appropriation” have any place in this debate? And is Bruno Mars, at best, his generation’s most talented tribute artist or, at worst, a thief? In a sequel to their conversation on appropriation, New York music critic Craig Jenkins and Vulture music columnist Frank Guan attempt to untangle the mess.

If cultural appropriation is thought of as the theft of a minority culture by an oppressor, usually with malicious intent, how do we loosen the definition when people of color take from each other? And how do the rules apply to a multiracial person like Bruno Mars?

Craig Jenkins: I feel like the answer to this question sits at the dawn of hip-hop, which was set in motion by a Jamaican immigrant in a community of black and Latin Americans and patronized early on by artsy downtown white folk. It was always a multiracial enterprise by nature of the lay of the land here, and I think that speaking of hip-hop as though it was historically an exclusively black art is not only a misunderstanding of how the culture worked from day one, it’s a disingenuous flattening of several conversations about racial identity and cultural exchange. Was Latin funk appropriation? Was the Rolling Stones’ “Miss You” a robbery? Should Eve’s “Who’s That Girl” have done more to lift up Latin music? Was Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain a form of theft?

The main evidence of appropriation in the YouTube roundtable discussion was the sense that hurdles that existed for black artists in the ’80s aren’t there for Bruno now, and that his “racial ambiguity” is an ace in his pocket, getting him places that Michael Jackson and Prince had to fight structural music business racism to reach. You could honestly make the same argument about less racism equaling increased access for everyone working in rap and R&B now, except I’m not so sure the America that marches for white supremacy by tiki torch and sets ICE traps for Dreamer activists is this happy to see a brown guy flourishing. And the shakiness of the insinuation that “ambiguity” played no part in Prince’s celebrity when it was a major thread is not lost on me.

It’s true that things were worse for black art 35 years ago. But it’s not the fault of an artist born in 1985 that that happened.

Frank Guan: There are a lot of charges buried in the Bruno affair. There’s resentment against the fact that he’s not an original artist. There’s resentment against the fact that white people hold nearly all of the social and economic power in America. There’s resentment against the fact that Bruno won Grammys over black artists who are original. Basically, the idea is that black people do a lot of work, creative and otherwise, and don’t get recognized for it, while Bruno doesn’t, and does?

There is truth behind all of that, and yet the idea that Bruno Mars — harmless, charming Bruno Mars — is some kind of pirate seems frankly ludicrous. I just don’t see the knife in his teeth. Bruno’s palatability to white listeners was held against him, while the fact that he has plenty of black listeners as well was skipped over. Not to mention those listeners who aren’t black or white.

Jenkins: Let’s take down the Grammy angle real quick because black artists and the Grammys have been in a war for as long as I remember. In 1989, the whole hip-hop community famously boycotted because the show wouldn’t air its inaugural rap award. In 2018, they still don’t show the R&B awards in broadcast. They’ve stiffed black artists on Album of the Year for several years. This year looked like a change of pace with Jay-Z, Childish Gambino, and Kendrick getting nominations for the top honor. I was miffed when DAMN. lost, but the sight of talented guys like songwriter James Fauntleroy, who writes for Mars, onstage accepting for one of the most prestigious music awards shut me up immediately. Does 24K Magic deserve that honor? Maybe not. Were black artists robbed because it won? That’s a stretch.

Are the merits of the work still valid if black artists were hired to make and perform the work, but a non-black person is its face? We know Bruno Mars is careful about credit; he paid Trinidad James for the use of a lyric in “Uptown Funk.” But Mars has also been accused of stealing more than just a “vibe” from dozens of other black artists for that same song.

Jenkins: Childish Gambino’s “Redbone” is a sorta obvious retread of Bootsy Collins’s “I’d Rather Be With You,” but the writing credits went to Donald Glover and producer Ludwig Göransson. Gambino’s entire Awaken, My Love! album was very specific ’70s funk fan service, and I loved that about it — as did fans and the Academy. By the same rule that says a half Puerto Rican guy with a black band is stealing black culture, should we not be mad at a black guy and a Swedish guy repurposing Parliament/Funkadelic licks? I don’t think so, but I don’t think anyone talking loudly about appropriation in pop music pays very much attention to who else is in the room during the making of a record. If they did, I’m not sure we would be having this conversation.

Guan: Bruno isn’t just a face, but a body that dances, too. You can’t really separate that aspect of him from the music itself. I don’t think you can see him dance and think, Oh, he’s just ripping off black artists. If you dance well, that’s all you.

This was what allowed rock and roll to slide on the whole cultural appropriation front for so long: Guys like Jagger or Plant or Rose had a physicality to their stage presence that, though impossible to achieve without the example of black rock artists before them, was entirely their own. You can’t copy someone’s relation to their own body, but you can, if you’re inclined and persistent, use it as a model to arrive at your own relation to your own body. Music isn’t dance, but the parallels between the two are fairly obvious.

Jenkins: I do think that anyone who watches Bruno dance for any length of time ought to see he loves it and he means it. What’s more, showing respect to his forebearers and getting checks for talented black and brown peers is paying it forward, and to me, the definition of “cultural appropriation” is taking from other cultures without giving anything back. That’s not what this is.

Is there a difference when Bruno takes from R&B wholesale, and when Drake takes from other, not-famous-enough black artists, sings in patois, or cribs reggaeton music and Latinx slang? Or when Kendrick Lamar takes from kung fu? How do we measure the crimes, if there are any?

Jenkins: I mean, Wu-Tang Clan got a lot of its lore and iconography from ’70s Hong Kong kung fu cinema, and we bop to that shit, no questions asked. The Toronto rap authorities I looked to when Drake adopted patois said that he was tapping into a pan-African spirit in their local culture that is lost on Americans. I don’t see why our understanding of what Bruno does for better or worse can’t be more fluid.

Guan: If Bruno were pulling a Drake and lifting phrases and flows and beats off other young artists who aren’t as famous, we’d never hear the end of it. What Bruno’s doing is paying homage to artists who have already had their day, and the fact that he’s gotten a pass for so long suggests that he knows what his position is, and knows not to push his luck.

Kendrick isn’t stealing from Asian musical artists, he’s just taking on the trappings of an Asian subculture. He’s doing the Kung Fu Kenny stuff out of affection, and he’s certainly not doing it because he doesn’t have a style of his own. It’s not like he’s shooting music videos framed like Asian action flicks where he massacres a bunch of Asian dudes or anything, which is something Post Malone and the Migos have both done recently. Now that stuff is troublesome, but it’s also not really worth kicking up a fuss about either. You’ve got to keep a sense of proportion.

Honestly, I think a handful of people are coming for Bruno now because all the easier game has been taken down already. Iggy Azalea got whisked out of the paint. Justin Timberlake didn’t dare to perform with a Prince hologram once people found out.

Jenkins: I saw enough of Prince to be mad.

Guan: The problem with seeing culture exclusively through the lens of a prosecutor is that, much like real prosecutors, you’re always looking for new cases to convict. The discourse of appropriation has done just about all it can at this point.

Jenkins: There are cases right now, though. You have guys like rapper 6ix9ine popularizing “blick,” which is derogatory slang for dark-skinned people. You have white rap influencers encouraging white people to say the N-word on air. You have white vloggers who don’t have all of their facts in place reviewing rap with authority. Take the fight where it counts and leave all these talented black and brown folks be.

Guan: I don’t have the time to get mad at Bruno Mars or to be anything more than a bit somber over the fact that some people think Bruno is worth attacking in 2018. Like, have you seen who the president is?

Now that the Bruno Mars debate has been reignited, do we need a new vocabulary to consider and engage with forms of pastiche and homage between minority cultures? What does acceptable cultural borrowing look like between people of color?

Jenkins: There absolutely must be a more refined conversation about how culture passes between different minority groups, and I don’t want anyone to come away from this thinking the gist of my point is “Bruno is not all the way white, so he can’t be stealing.” This debate is really about calling down holy retribution on an album whose entire spirit was showing respect to the old school. He looks at Teddy Riley [who has defended Mars, praising his work as homage] like a king and even got Shai a check for a sample on “Straight Up and Down.” Few of the current faves have dared.

Guan: If such a new vocabulary exists, it wouldn’t exist purely or even primarily within the cultural sphere. Most of the current discourse just assumes that the American situation is the only situation there is, which is to say a white majority with money and connections set against a black minority with artistic brilliance. Whereas most people in the world aren’t black or white, and have musical and other cultural traditions that simply don’t fit into the black-white binary. I get why there was so much backlash against rapper Rich Brian back when he was controversially named Rich Chigga, but at the same time, it’s not like Brian was coming from a place of towering privilege either, or that he didn’t have a sound of his own. There’s no substitute for educating yourself about the entire world. White privilege is real, anti-blackness from people of color is real, male privilege is real, economic class privilege is real, but if you don’t know how to account for your privilege as an American, you’re not playing with a full deck.

Jenkins: Rich Brian set the sensors off on himself, but I do agree that the way the conversation about race unfolds here is 100 percent specific to the terrible history of this country, and that outlook doesn’t always translate well to or speak for people who exist outside of it.

I’ll end by going back to what I was saying earlier, which is that the idea that genre boundaries in ’90s hip-hop are solid is crazy to me, as a New Yorker who has probably spent the majority of my life north of Central Park. We grew up hearing rap, R&B, house, freestyle, salsa, merengue, and dancehall, and sharing neighborhoods and party spaces. The closeness of these cultures is present in the rap from that era — stop and think of how many classic rap albums have a dancehall toast in ’em – and to pretend these cultures are not meaningfully intertwined and try to hand out roles to people by circumstance of birth just seems … I don’t know … young? But this is the same social-media sphere that doesn’t understand what an Afro-Latina is and accuses African-Americans of appropriating African culture for wearing dashikis to Black Panther. The conversation about race is flat, when the reality of identity is multidimensional.