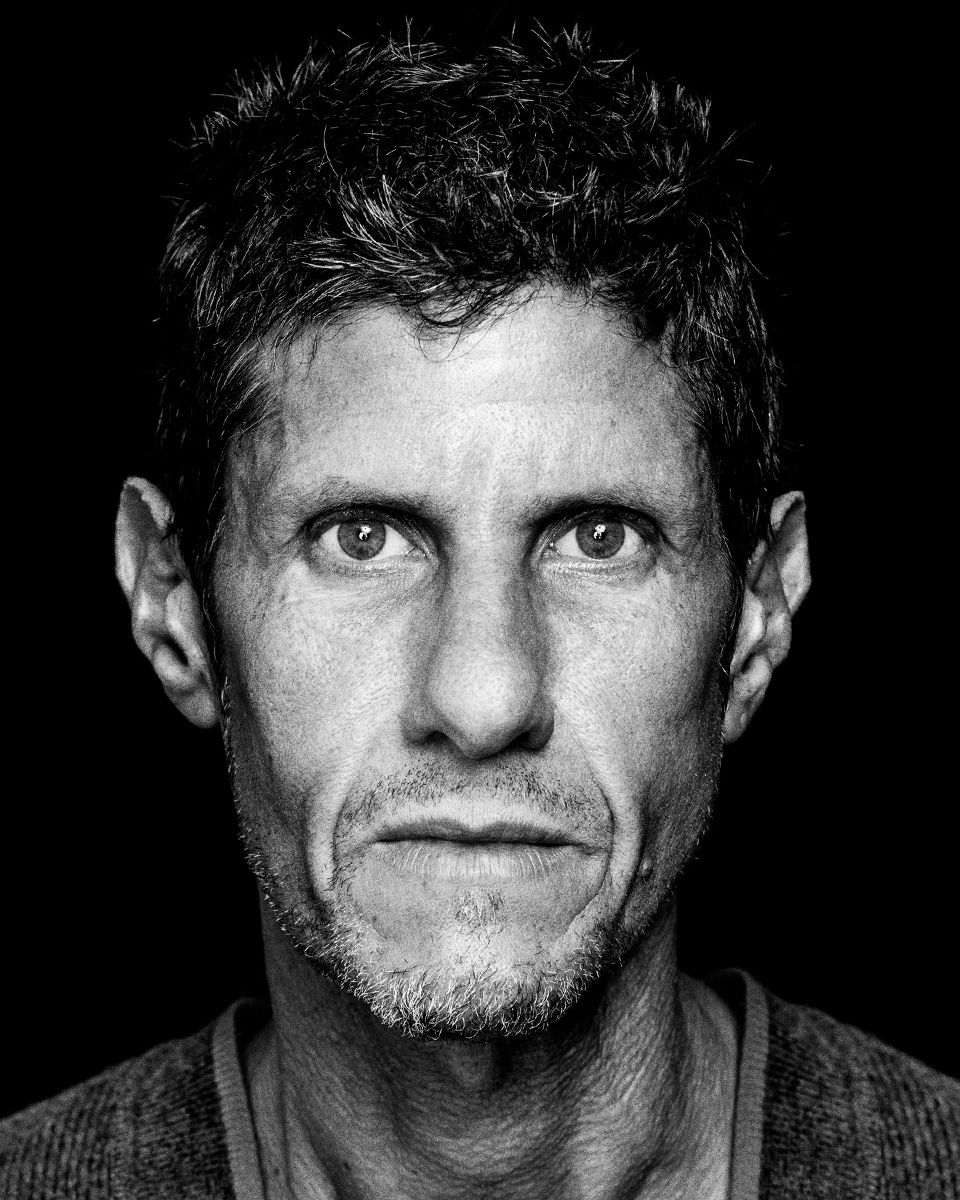

When the Beastie Boys’ career came to a tragic halt in 2012 after the death of Adam “MCA” Yauch, the remaining band members, Adam Horovitz and Mike Diamond (known as Ad-Rock and Mike D respectively), were faced with the difficult task of creating futures for themselves that weren’t mired in the past. “For three decades I was totally consumed with being in the band,” says Mike D, rail-thin in a leather jacket, sipping tea in the lobby of the Bowery Hotel. “Identifying what else I was comfortable doing with my life was a very gradual process.”

What he’s settled on has been both comparatively low-key and deeply enviable. Mike, 52, hosts the Beats 1 radio show The Echo Chamber, takes occasional production work and DJ gigs, globetrots with his kids, and has written an eagerly anticipated memoir with Ad-Rock. Thirty-seven years after forming the band, Mike can say, with a smile, “I learned a lot of things in the Beastie Boys — including how to appreciate a good time.”

Has working on the book affected your thinking about the Beastie Boys’ career? The conventional narrative, as I see it, is that there were three defining milestones for you guys: Licensed to Ill, Paul’s Boutique, and “Sabotage.” Does that jibe with your understanding of the band’s trajectory?

No.

How do you see it?

What you described is an easy way to look at a timeline and pick out a few blips.

But it’s not based on nothing. Licensed to Ill was your biggest-selling album, Paul’s Boutique is considered, pretty much by consensus, to be your best album, and the “Sabotage” video gave you a new audience. What’s missing there?

It isn’t based on nothing — it’s just based on a simple timeline. There are a million moments that lead up to those moments you picked out. With Paul’s Boutique, for example, we were three fools trying to make something we loved. We didn’t realize it was going to flop. But its flopping gave the album room to be embraced by people that didn’t or couldn’t connect to Licensed to Ill. There was also a big void for us after Paul’s Boutique. That album put a stink on the band because it sold so poorly. Nobody wanted to work with us, and that gave us the creative freedom to make Check Your Head. Then the process of finding a new audience and building new music culminated with Ill Communication and “Sabotage.” Out of all that came the commercial success of Hello Nasty. So there’s the timeline, but with a bit more breadth or width.

I know I’m putting you on the spot with another career-spanning question, but what’s the weirdest or funniest reference the Beastie Boys ever snuck into song? “I’ve got more hits than Sadaharu Oh” is the one that kills me.

So you like that one? Was Sadaharu Oh a more obscure reference than, say, Rod Carew?

Rod Carew was an American League MVP!

But Sadaharu Oh was the Japanese baseball player that Americans could name. Let me think … George Drakoulias is a reference that was probably hard for people to get. Now you have me thinking about Paul’s Boutique. I’m happy that we have a lot of New York references on there, whether it’s Drakoulias or Ed Koch.

Let’s talk about New York for a bit. You’ve lived primarily in L.A. for a while but I’ll always think of the Beastie Boys as being quintessential New York characters. Do you still feel connected to the city?

Well, my mom lives on the Upper West Side where she’s always lived. But this is something I talk about with friends: It’s ironic that we had so much autonomy growing up here in the city in the ’70s and ’80s and now kids are so connected to their parents through their phones, even though the city is far safer. New York is infinitely different now than it was when I grew up. It was far more dangerous for us in every way. You wouldn’t have a car radio because you knew it’d only get stolen. Riding the subway could be nerve-racking on a number of levels. The city felt so much more lawless. And yet the families that did stay here instead of move to the suburbs had a commitment to being here and letting their kids explore. As an individual and a band we couldn’t have become who we became without that freedom and that exposure.

Given how important freedom and exposure were to who you became, do you worry about your kids missing out on those kinds of experiences? They’re growing up in a radically different environment than you did.

Obviously issues come up. There are teen-angst issues that are real. I have to constantly remind myself of how much anger I had at 15 years old for relatively little reason. I find myself interested in the different phases of music my kids have been into, from commercial rap like Kanye and Drake to the hard core that I grew up on like Black Flag and Bad Brains. And then there’s getting into Slayer, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin — the emergent testosterone classics.

What’s interesting about those phases?

I kept asking myself why that music hasn’t been totally replaced. It was weird to me that I wasn’t hearing things that my kids related to that I couldn’t embrace. When they did hit on something, I was like, Finally!

What did it?

When they started listening to $uicideboy$ I was like, “That’s it. That checks the boxes.” It’s really loud, I can’t really relate, I don’t really want to listen to it. I understand exactly why it’s good and I see exactly the music it’s combining, but I don’t need to participate and I’m good with that.

There was a period in the ’80s when the Beastie Boys were considered a band that parents could have problems with. Do your kids have any sense at all of what you represented?

That’s a tricky question. Obviously they know who I am but relating that to the music or the persona of the Beastie Boys is an abstract thing. I guess the only way they’d relate to it is if some friends were listening to our records. I think then my kids would be like, “Why would you do that?” They have to listen to me all the time. Listening to my music wouldn’t be fun for them — at all.

But my question about upbringing: I was trying to get at whether or not you think your kids are missing anything formative by being raised so differently than you were, and not just in a musical sense. I mean in deeper ways.

A huge amount is lost. It’s very sad to me, honestly. But I don’t know, I’m hopeful that there’s some unbelievable cool shit going down in the city — what Bushwick would’ve been five years ago. Wherever that is now I don’t know about it. This city is just so fucking expensive and for so long there was a way for culture to exist in its own, perverse, self-governed way. That’s largely gone now. You can’t have a studio here, the cost is so great. And the cost of that has been to box out culture. I still feel innately comfortable in New York — I beyond enjoy it — but at this point in my life I’m nomadic. I was just living in Bali for four months with my kids.

What appeals to you about being nomadic?

Having lived that way on tour since I was 18. It’s what feels natural to me. Also, I’ve realized that— this is maybe too heavy for this interview.

Heavy is okay.

After what happened with Adam [Yauch], I realized that life can be short. Especially being a parent, the moments I appreciate most are when I’m with my kids and we’re all experiencing something together. It’s very difficult to do. Your kids get older and become more autonomous, and when you’re in that cave of Brooklyn or L.A. you’re going to default to a certain mundanity of existence. That’s not what I’m in the market for.

What are you in the market for?

I think our lives are much more meaningful when where we’re moving around and experiencing things together. This is making me think about New York. I’m just playing with this in my head with you right now: When I grew up in New York, the city was unique in that you could get music from all over the world here. Now you can get any music you want on your phone and New York, or Manhattan anyway, seems a lot less diverse.

So your moving around is about trying to avoid cultural homogeneity?

It’s that I want my kids to experience diversity. I think it’s important to travel the world with them. And it’s also about breaking open the myth that the United States is this leading majority. We’re not. Indonesia, where we’ve been living, is going to overtake the U.S. in population within my kids’ lifetime. I want to my kids to have the opportunity to see themselves as a citizen of the world and not only America — whatever the hell America means today. At this point, in the world of Trump’s politics, there’s so much upside to be had by breaking down the whole idea of nationalism. My kids’ peers at school are from all around the world, not just the Upper West Side or Brooklyn. I really think that helps them think differently about the world in a positive way.

Not to play armchair psychologist, but don’t you think your desire to avoid mundanities, as you put it, is about filling the empty space where the Beastie Boys used to be?

I wouldn’t disagree with that. Like I said, uprooting myself or challenging myself was my normal for decades.

Did uprooting from New York to L.A. change the band?

It’s funny because Paul’s Boutique, which is still a very New York record, was made in L.A. So you could take us out of New York but you couldn’t take the New York out of the band. But there’s a flip side to that, which is that the experimentation that we went through from Paul’s Boutique onwards, and certainly with Check Your Head and Ill Communication, came from the luxury of having our own studio in L.A. — this big space with skateboard ramps. We had that space for a long time, we called it G-Son, and we’d just fuck around there for hours on end. That’s what our recording process was, and that’s a space-and-time luxury we had in L.A. that we wouldn’t have had in New York.

This is slightly random, but I’ve always been curious: What happened to the country album you guys recorded?

I probably shouldn’t even bring attention to the fact it exists.

Can you remember what one of the songs was called?

“Sloppy Drunks.” Even talking about this — it makes me think that it’s hard to convey how truly Monty Python–esque it was to live in the Beastie Boys’ world.

What’s another example of that absurdity? Is there a story that comes to mind?

Yeah. After we started working with Russell Simmons as our manager, one of the first hip-hop shows we played was at this club called Encore in Queens — Jamaica, Queens, I believe. We were so fucking stupid. We were like, “Oh, we have a real gig. We’re going to rent a limousine to get us there and get us back. We’re going to go out.” We’d take all the money we were going get, all $125 or whatever it was, and hire that limousine. So we got the limo and because Run-D.M.C. was wearing Adidas suits at the time, we wore matching Puma suits — that’s where it was at. We were opening for Kurtis Blow, I think, so it was a big deal. So we get there and we, this bunch of white kids from Manhattan dressed in Puma suits, step out of the limo. The first comment we heard was, “Who the fuck are you guys, Menudo?”

That instance aside, in terms of racial and cultural dynamics, the Beastie Boys never pretended to be anything you weren’t. But subjects like cultural appropriation are hot button in a way they weren’t in the ’80s. From your perspective, how has the cultural position of the white rapper changed?

I’ll say that when we pulled up in that limo wearing our Puma suits — that was the first and last time we did it. We realized we looked like fucking clowns and we felt like fucking clowns. We had to learn to be ourselves, and we made it work culturally and were accepted as rappers because were able to be ourselves and not anybody else.

But is what listeners are willing to accept from white rappers today different than it was 30 years ago?

That’s a tricky question to answer. I don’t know what people are willing to accept. It’s an interesting time because theoretically everything’s been done already and everything is culturally available. Ideally that means there are fewer cultural barriers. In theory whatever someone is influenced by should be inclusive and available to them. In practice, I don’t know if that ends up being the case.

Licensed to Ill was the first rap album to go No. 1 on the Billboard Top 200. Did hip-hop’s becoming the basis of pop, like it is now, feel inevitable to you?

I always felt like rap would become popular but I didn’t foresee it becoming as mainstream as it is. With current rap, there’s nothing that makes it not pop. Obviously certain rappers are going to make poppier records and certain rappers are going to be more esoteric, but I never would’ve thought that rappers could be the Lionel Richies of their day.

You mean as far as being beloved pop figures?

Yeah, that Jay-Z or Migos would be in that same position — not in terms of music but in terms of universal acceptance. I did foresee that we’d get something like an OutKast — rap that could sell millions and still feel not pop. But now we’re in a stage where rap isn’t separate from pop, which is amazing.

Are you seeing the Beastie Boys’ influence anywhere in the culture these days?

It’s interesting, because there are so many things that I appreciate musically, but I don’t ever think of them as Oh wow, that’s like what we did. I just don’t see things through that lens. Something that always makes me cringe is when somebody says, “You gotta hear this. They’re like you guys.” That usually doesn’t end well.

Can you remember something you’ve been played that was supposed to sound like the Beastie Boys?

This is an old thing, but I remember seeing Dee Barnes at a club and she said, “You’ve gotta hear this new group, Cypress Hill. There’s something about their voices that reminds me of you.” That’s kind of the best-case scenario.

What’s the worst-case scenario?

Not that it’s ever happened, but my fear would be that someone would be like, “311. You love those guys, right?” I’m sure they’re nice people — [their music] isn’t my cup of tea.

For obvious, tragic reasons the Beastie Boys had a definitive ending. Did having such a sharp break between your past and future make it harder to reorient your life moving forward?

It took a while. Yauch dying was so tragic, on so many levels, that it took a profound period of grieving to then be able to start figuring out what I wanted to do.

What’d you arrive at?

I don’t know — it’s all different things. I like doing the radio show because it replaces the process we had as a band of generating ideas by playing music for each other. Now I do that with guests on the show. Actually, when I produce other people’s records, asking “What have you been listening to?” is always my starting point. So those are things that would take place in the band that still take place now. I guess what I’ve also realized is that I like it when people approach me about something that feels outside my comfort zone. Whether it’s curating a music-and-visual art show with Jeffrey Deitch or working on a wine list for a restaurant. I’m interested in trying to do things that I feel like I have no business doing. Because that was part of what we did as a band. We weren’t afraid to try shit.

You mentioned how important sharing music with each other was to the Beastie Boys. I think it’s fair to say that you guys used to perform a similar curatorial function for your fans. I remember so vividly learning about cool music from Grand Royal or by figuring out the references in your lyrics or what samples you’d used. Technology has obviously made that kind of digging so much easier. Has that change — that ease of access — had an affect on how listeners feel about music?

The filters are still there, though. They’re just different. When I was 15, getting into the Clash exposed me to reggae. I’d see that they covered a song by Junior Murvin or that they had a single produced by Lee Perry and dig from there. My younger son does the same thing but in newer ways. He comes home from school in Bali and starts to make a song using his laptop, and he’s looking up what samples Kanye used and that opens the door for him to dig. The tools he has are immediate. He’s not having to go out. It’s so different from how I did it. I used to have this ritual when I was going to school in Brooklyn Heights and living on the Upper West Side. I’d always get off the subway in downtown New York to go to record stores. It was so exciting going to St. Mark’s Sounds to find reggae records or to 99 Records and sheepishly asking Ed Bahlman, “What’s cool?” That was the way. Now my son, Skyler, can do all the equivalent searching online. Proximity to the culture is no longer an issue for learning about it.

Does that matter?

I don’t know. Discussing curated filters is very three years ago.

Say, have you heard that the future of music is “streaming”?

[Laughs] I just think that people have already succumbed to the idea that they’re constantly overwhelmed with digital information. They don’t expect to be able to rise above it intelligently anymore.

Just to go back to the band a little more specifically: Did your relationships with the two Adams change over time? From what I’ve read, in the very early days of the Beastie Boys they occasionally gave you the business — almost in a young-male hazing way.

Really? I don’t remember that.

There’s that story in an oral history of the band where the other guys dumped dirt in your hotel bed.

Yeah, but we were a band. We’d fuck with each other constantly. I strongly disagree with the hazing [characterization]. We would all fuck with each other. That was just part of it. Hazing sounds like some kind of frat thing. The only fraternal aspect of it was that Yauch and Horovitz and me became like brothers.

A couple years ago, there was a good GQ article about Horovitz that suggested that he was struggling a little to find his Next Big Thing after the Beastie Boys. Has that been your sense of his experience?

With Adam, it’s so hard for me to say because I love him so much and think he’s so supremely talented and funny. The band was an incredible outlet for all of that and if you have an outlet like that, it’d be unreasonable to think there’d be an immediate transference of that outlet to a new one. It’s going to take trial and error; you have to be okay with failing in the process of finding those new outlets. Adam also has a young child. My kids are much older. Young kids are a hands-on-deck experience. For what it’s worth, I will say that his writing for our book has been so great — dude is very, very funny. I would even nominate him to be in the category of classic New York funny person à la Woody Allen, Chris Rock, Noah Baumbach. Adam belongs in that group.

Did the three of you have an inkling of what the band’s next big move might be after Hot Sauce Committee Part Two?

Full disclosure, the plan was always to put out Hot Sauce Committee Part One.

Good title.

You can file it under the category of “funny to us.”

What’s something in your life today that gives you same the thrill as the one you get from music?

I’d put surfing in that category. It truly is intoxicating — it’s probably the endorphins that does it. One of the most profound things about it for me is that in this era when we are all connected all the time, [surfing] is time out of the day where not only are you not connected to any device, you are connected to the ocean, a power far, far greater than you. You become this little speck, and if you are not present and don’t respect the ocean, you will be demolished by a wave.

Are there emotions common to surfing and making music?

Yeah. I think musicians can become addicted to surfing very quickly because there’s overlap. Musicians are always chasing this fleeting transcendental feeling in the writing or playing of music where the rest of the world ceases to exist. Surfing is a simile for that experience. You’re getting the same sort of energy in a totally different form. Do I sound like a West Coast douche?

Because you’re describing the cosmic qualities of surfing?

[Laughs] “Wow, I helmed this wave and I was just going and I was connected to it and there were three dolphins swimming face to the wave. And then I turned into a moon maiden …”

Did the transcendent feeling you were talking about — with music, not surfing — get more or less common as the Beastie Boys’ career went on?

I think what happened is that as I got older, I become able to recognize that feeling and appreciate it in the moment that you’re feeling it. Whereas when you’re 18 or 19 years old, you’re on lizard-brain autopilot. If something feels good, you’re just trying to make it happen again.

We’re kind of joking around here, but the idea of a New Yorker moving to California and becoming a laid-back surfer-guy is almost a cliché you could imagine the Beastie Boys having fun with in their younger days.

Yeah, I can see that. Although I could have grown up my whole life surfing in Rockaway. There are really good waves in New York. I feel sort of like an idiot that I didn’t take advantage. But L.A. hasn’t totally changed me. I’m still neurotic.

About what?

I’m pretty phobic about being an adult, even downright scared.

What would the 25-year-old Mike D would think of the 52-year-old Mike D?

That’s a very good question. Let me say one thing and then I’ll answer it more directly. Adam Horovitz, Adam Yauch, and myself used to have this joke on tour: You’d go to gate-check a bag at an airport, and there’d be a guy there who was 40 years old and who’d listened to Licensed to Ill in high school. And he’d be like, “Oh hey, Beastie Boys! You guys are still doing it, huh?” There were obviously fans that followed us throughout the band’s livelihood, but then there were people like the guy at the gate-check who’d had their time listening to Licensed to Ill or whatever and that time in their life had passed. And they’d be like, “Still doing it, huh?” Anyway, my point is that I’m very grateful at my age that I’m able to do stuff that I love. I guess I can say it like this: Adulthood is overrated; maturity is underrated.

So the young Mike D would be happy with where he wound up?

The 25-year-old me? I remember around that age, when we were working on Paul’s Boutique, we went to this crazy, star-studded party and I met Bob Dylan. I guess I hope that I come off as eccentric as Bob Dylan came off to me back then.

That’d be hard to do. He’s a pretty weird guy.

I didn’t say I was achieving it.

Right now, though, in this moment, when I ask you to think of the Beastie Boys, what’s the first thing that pops into your head?

It’s not one event. It’s the process of Adam, Adam, and myself collaborating on every level: making records, making videos, making record covers — all of it. I think about the longevity and the closeness that the three of us had. It’s really — what is the correct adjective to express family?

Familial.

That’s what it was, and that’s what it is.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

Annotations by Matt Stieb.