Odds are that most writersÔÇÖ efforts are doomed to oblivion, and for critics that fate is practically guaranteed. Their judgments can launch other writers and artists to fame (or perhaps do the opposite), but once the launch is accomplished the memory of a criticÔÇÖs praise is jettisoned like the boosters on a space shuttle. Page through any criticÔÇÖs collected reviews and youÔÇÖll find raves and pans of works lost to time. Perhaps the best posthumous audience a critic can hope for is one composed of other critics, whoÔÇÖll rummage through their predecessorsÔÇÖ out-of-print books and stray clippings after the yellowed records of youthful verdicts and forgotten feuds.

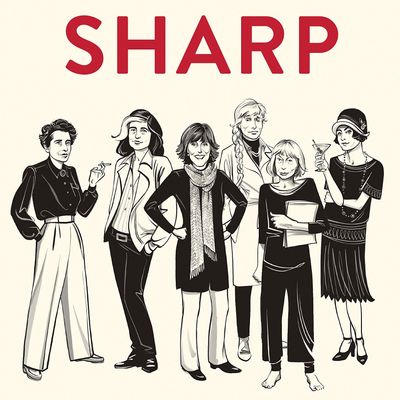

ThatÔÇÖs the project of Michelle DeanÔÇÖs new book Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion. Dean tracks a set of writers born between 1891 (Zora Neale Hurston) and 1941 (Nora Ephron) and considers them mostly as critics and particularly as women breaking into a field dominated by men. Across these portraits itÔÇÖs possible to trace currents in American literary history as it unfolded between World War I and the present. Forms that could once make a writer famous turn out to have shorter shelf-lives than graffiti. Film, both as a critical subject and a creative pursuit, attracted many of these writers in ways that were alternately productive, lucrative, and largely a waste of time and talent. They operated during the long golden age of American magazines, both little and glossy, an era that is certainly over, though itÔÇÖs unclear what sort of dispensation, for readers and writers, will follow.

Dean focuses on her subjectsÔÇÖ moments of emergence: These tend to involve both a lucky opportunity and a moment when a writer discovered her own powers. Dorothy Parker, Rebecca West, and Renata Adler were prodigies. Pauline Kael and Janet Malcolm were late bloomers. Hannah Arendt and Susan Sontag made their way through universities and then burst on the public scene. Joan Didion had a novel to her name before she wrote the features for the Saturday Evening Post that turned her into an icon and still account for a disproportionate share of her reputation. These origin stories ÔÇöusually paired in DeanÔÇÖs telling with one or more public controversies and in some cases a crucial marriage or love affair ÔÇö are fun to revisit and for the uninitiated Sharp is a valuable introduction to an essential group of writers. For aspiring writers especially, these women are required reading.

But how much are they read today and do we read them the right way? Of DeanÔÇÖs subjects, only Pauline Kael counts as purely a critic, and she remains influential because many of the major film critics working today started out as her acolytes, the so-called Paulettes. But the recent surge in socially conscious pop-culture criticism spurred Jaime Weinman, writing in Vox, to suggest that ÔÇ£the end of KaelismÔÇØ has arrived. Politics werenÔÇÖt necessarily symbiotic in KaelÔÇÖs scheme of thing. Indeed, good or well-meaning politics could be the source of a filmÔÇÖs, or a whole decade of filmsÔÇÖ, flaws. Here she is on the turn of 1930s Hollywood screenwriters to communism:

The writing that had given American talkies their special flavor died in the war, killed not in battle but in the politics of Stalinist ÔÇ£anti-Fascism.ÔÇØ For the writers, Hollywood was just one big crackup, and for most of them it took a political turn. The lost-in-Hollywood generation of writers, trying to clean themselves of guilt for their wasted years and their irresponsibility as writers, became political in the worst way ÔÇö became a special breed of anti-Fascists. The talented writers, the major ones as well as the lightweight yet entertaining ones, went down the same drain as the clods ÔÇö drawn into it, often, by bored wives, less successful brothers. They became na├»vely, hysterically pro-Soviet; they ignored StalinÔÇÖs actual policies, because they so badly needed to believe in something. They had been so smart, so gifted, and yet they hadnÔÇÖt been able to beat HollywoodÔÇÖs contempt for the writer.

The passage is from her 1971 essay ÔÇ£Raising Kane.ÔÇØ The essay is controversial for her claims on behalf of Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz at the expense of director Orson Welles and her use of research done by UCLA film professor Howard Suber, whose work she had agreed to publish along with her own as introductory material in a paperback edition of the filmÔÇÖs screenplay, but itÔÇÖs remarkable for her broad argument for ÔÇÖ30s comedy ÔÇö especially in the figure of the cynical newspaperman ÔÇö and the decline of comic writing in the ÔÇÖ40s. This was the generation led by Dorothy Parker.

ParkerÔÇÖs career now reads like a cautionary tale. Her wit became famous from her theater and book reviews and reports of her lunchtime banter at the Algonquin Round Table in Franklin Pierce AdamsÔÇÖs newspaper column ÔÇ£The Conning TowerÔÇØ (when informed of Calvin CoolidgeÔÇÖs death, she asked ÔÇ£Really? How can they tell?ÔÇØ). Volumes of her light verse were best sellers. The short story was still a commercial form, and Parker wrote one classic, ÔÇ£Big Blonde,ÔÇØ which won the OÔÇÖHenry prize in 1929. In Hollywood she was nominated for an Oscar for the screenplay of A Star Is Born. She made four figures a week during the Depression. ÔÇ£I just sat in an office and did nothing,ÔÇØ she said. She had marched for causes in New York, had been fined $5 in Boston for protesting the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, became more political in California, and by the 1950s was blacklisted as a communist. During the war The Portable Dorothy Parker had become a hit among GIs and it remains the best way in to her work. There was never a novel. When she returned to New York to live alone in a hotel, write for the stage and for Esquire, she spoke with some bitterness of the old days. ÔÇ£Dammit, it was the ÔÇÿtwentiesÔÇÖ and we had to be smarty,ÔÇØ she told a Paris Review interviewer in 1956. ÔÇ£I wanted to be cute. ThatÔÇÖs the terrible thing. I should have had more sense.ÔÇØ All the writerly vices come together in her story: selling out, alcoholism, stridency, ostracism ÔÇö everything but suicide, which she attempted five times.

It was the ÔÇ£twentiesÔÇØ: Parker knew that writers are captives of their times. This was an advantage for Mary McCarthy, who arrived in Manhattan in the mid-1930s among a milieu of Stalinists (her unfinished Intellectual Memoirs give the impression that this was true of almost everyone she knew), gave a casual answer at a party when the novelist James T. Farrell asked her whether Leon Trotsky deserved a fair hearing, and soon found her yes had landed her name on a list of members of a committee for her defense. She was going to have her name removed until she found out that others, like Freda Kirchway, editor of the Nation, were doing the same. She left it on to be contrarian. This put her in the company of the Trotskyites who were restarting Partisan Review, free of its former Stalinist ties (and funding), among them McCarthyÔÇÖs sometime boyfriend Philip Rahv. The break with Stalinism also kept the magazine on the side of the modernist avant-garde, and from within its inner circle McCarthy was ideally placed to do it all. She wrote short stories that resounded across the country: ÔÇ£The Man in the Brooks Brothers ShirtÔÇØ was the ÔÇ£Cat PersonÔÇØ of its day ÔÇö Dean quotes George Plimpton on the shockwaves it sent through his boarding school campus in New Hampshire ÔÇö and became the heart of her novel in stories The Company She Keeps. She would write a megaÔÇôbest seller in The Group ÔÇö a book that would create its own genre, the collective portrait as chronicle ÔÇö but also works of art criticism, on Venice and Florence, and political commentary, on Vietnam and Watergate. Strangely (to me anyway), of all DeanÔÇÖs subjects, McCarthy is currently the most neglected, despite the Library of America editions of her novels issued last year. It may be hard to do at the moment because she was such a creature of her time, a novelist as annalist and a polemicist fighting it out on the (Cold War) ground. Is this also true of Kael? Her selected writings now appear under the title The Age of Movies. Is that era over, now that weÔÇÖre living in the age of prestige TV recaps?

The generation that followed McCarthy ÔÇö represented in DeanÔÇÖs account by Joan Didion, Susan Sontag, Renata Adler, Nora Ephron, and Janet Malcolm ÔÇö operated in her shadow and under her influence as well as that of her friend Hannah Arendt. Adler was for a time engaged to McCarthyÔÇÖs son Reuel Wilson, and Sontag may have been told once at a party by McCarthy that she was ÔÇ£the new me,ÔÇØ though nobody remembers whether that actually happened. On the spectrum from Ivory Tower to Pop, Sontag worked from the pulpit and Ephron at street level. Their efforts as filmmakers ÔÇö SontagÔÇÖs experimental and financially draining; EphronÔÇÖs accessible and massively lucrative ÔÇö couldnÔÇÖt be more different, or farther away from Parker on the screenwriting assembly line. Between them Malcolm cuts a curiously single-minded path, beginning in middle age as a photography critic for The New Yorker (a second start after a first foray in the pages of The New Republic under her maiden name Janet Winn) and then becoming a reporter whose great subject was subjectivity itself ÔÇö the hazards of journalism for both reporter and source.

The most fascinating pair in Sharp to scrutinize side by side is still with us ÔÇö Didion and Adler. Each has been a triple threat: reporter, critic, novelist. Both are members of the Silent Generation, born in the 1930s, children during the War, educated under Eisenhower, not yet adults at the time of McCarthyism and already mature by the arrival of the hippies. Though both have ended up as liberals, each began with conservative leanings. Didion was a National Review contributor and professed Goldwater voter. Adler wrote a sympathetic profile of G. Gordon Liddy and was at one point a registered Republican, as a form of quiet protest within her milieu at The New Yorker. Didion has written more novels (five), but Adler wrote better ones, better in part because more obviously personal even though a long-standing knock against Didion, made most famously by Barbara Grizzuti Harrison in 1980, has been that her real subject is always herself. This was never entirely fair, although DidionÔÇÖs way of fusing herself with her subject matter ÔÇö as she does in ÔÇ£The White Album,ÔÇØ disclosing a personal breakdown as if it were a symptom of the general malaise of the late 1960s ÔÇö yielded some unforgettable writing.

The great difference between Didion and Adler is that where Didion tended to see decline, atomization, and disorder in the culture (and in herself), Adler saw negotiation, transaction, and progress: a highly demanding theater of revolution rather than an actually violent one.

As a result, DidionÔÇÖs essays on the 1960s are now more thrilling to read but AdlerÔÇÖs are, without being any more or less factual, truer. TheyÔÇÖre also more astonishing. Here she is writing about her generationÔÇÖs experience in the introduction to her 1970 collection Toward a Radical Middle: ÔÇ£through the accident of our span of years, not too simple in the quality of our experience to know that things get better (The WarÔÇÖs end) and worse (the succeeding years) and better again (the great movement of non-violence sweeping out of the South to move the country briefly forward a bit) and of course, worse. But when a term like violence undergoes, in less than 30 years, a declension from Auschwitz to the Democratic convention in Chicago, from A-bombing even to napalm, the System has improved.

Terribly, and with stumbling, but improved.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs breathtaking to see napalm cited as a sign of progress, but the virtue of AdlerÔÇÖs youthful anti-apocalyptic vision was its embrace of the long view.

One difference between Didion and Adler is that Didion was, until she passed 80, consistently prolific. The books kept coming until her subject became the tragic disintegration of her family, the loss of her husband and daughter. There was time off to make money in Hollywood ÔÇö the biggest payday came for the screenplay she and her husband John Gregory Dunne wrote for the 1976 remake of A Star Is Born ÔÇö but it never derailed her literary output. Adler grew quieter over the decades and seemed mostly silent after her memoir about The New Yorker, Gone, and the controversies that attended it. But last year, to little fanfare, she published a long piece of bracing and beautifully turned reportage on the migrant crisis in Germany in LaphamÔÇÖs Quarterly. Informed by her own familyÔÇÖs experience as refugees from Germany in the 1930s, Adler embeds at a shelter for migrants (German: Asyl) in the Bavarian suburb of M├╝nsing. She observes the migrants as they take German lessons, do chores around the shelter, and form friendships. Some of them vanish from the scene without warning. Many have painful, even tragic, interactions with the state bureaucracy. Never shying away from the mundane, which in the lives of her subjects is shaped and constantly pierced by wretched forces of history, the essay oscillates between hopeful and heartbreaking tones, with the balance tipped toward the latter, and it concludes with a startling confession:

When I was young, in the 1960s, I wrote an essay deploring the ÔÇ£apocalyptic sensibility,ÔÇØ which foresaw, in every essentially political disagreement, the end of the world. I still deplore it. But I now have something very like that sense. It has been obvious for decades, at least since the year 2000, that Western civilization, perhaps mankind itself, is in jeopardy from various problems and directions. People tend to adopt one or more of these problems as political causes: pollution, energy consumption, inequality, nuclear war, racism, terrorism, global warming. As though any or all of them were within our capacity to resolve and bore the prospect of human extinction. In Germany, it began to seem that another, highly imminent serious threat, intended as a humane solution, has become the attempt to absorb distant, often hostile, foreign multitudes into what had been fairly homogenous and stable cultures.

The essayÔÇÖs final scene is an encounter with an elderly German man, a farmer, Adler meets at a bus stop. She asks him about the influx of migrants and he calmly begins quoting from the Book of Revelation, implying that the apocalypse has already arrived. The threat of course isnÔÇÖt the migrants themselves but the xenophobic right-wing politics that have returned, bringing the threat with them of the sort of state violence that made refugees of AdlerÔÇÖs family at the time of the Nazis. HereÔÇÖs hoping, along with Adler, that her younger self was right.