When Stanley Kubrick set about making 2001: A Space Odyssey in the 1960s, his goal wasnÔÇÖt just to make a movie set in space, a genre that, even then, already had a number of examples, ranging from gloriously terrible to pretty great. Instead, he sought to re-create the future: to reverse-engineer, using the best minds in design, science, and philosophy ÔÇö including and especially his own ÔÇö a likely, or at least possible, picture of what a human-inhabited outer space might look like, based off of aesthetic and technological trends on Earth. So fastidious and forward thinking was his work that a real NASA official called the London set of 2001 ÔÇ£NASA East.ÔÇØ

That his efforts coincided with the genuine peak of the space age, the release of his movie being followed a mere year later by an actual landing on the moon ÔÇö or a Kubrick-faked landing, if youÔÇÖre one of those guys ÔÇö is no coincidence. The 1960s were the first time in history that we could think not just imaginatively but scientifically about space travel, space habitation, and the metaphysical implications of space, and these developments kicked off a few boom years for artful space-fiction, with Rainer Werner FassbinderÔÇÖs World on a Wire and Andrei TarkovskyÔÇÖs Solaris following 2001 in quick succession. That sensibility would soon trickle into the mainstream, from Star Wars to Alien to Blade Runner, meaning that, by the release of the latter in 1982, weÔÇÖd had a full decade and a half of our greatest filmmakers lending a look, a feel, and, more than that, a vibe to space.

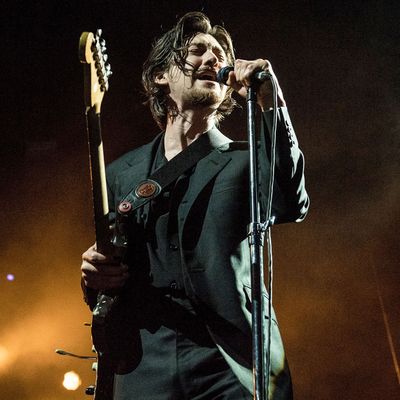

EERILY SOUNDTRACKED SMASH CUT to 35 years later, when Alex Turner, the lead singer of British band Arctic Monkeys, received a piano for his 30th birthday. Up to that point, Arctic Monkeys had released five albums of frenetic, danceable rock and roll, anchored by TurnerÔÇÖs clever lyrics and commanding yowl. While their most recent release, 2013ÔÇÖs AM, had incorporated a wide range of stylistic influences than ever before, this was still very much a guitar band making guitar rock.

So imagine fansÔÇÖ surprise and barely concealed dismay when it started to emerge that their first record in five years was: (1) called Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino, named for the spot on the moon where Neil Armstrong first walked in 1969; (2) took the form of, true to its title, a concept album about a hotel and casino on the moon; and (3) featured very few guitars, a scarce few songs that you could dance to, and a different version of the Alex Turner theyÔÇÖd come to know and love. A hairier version.

On the new album, Turner & Co. apply the tools of a 1970s soft-rock singer-songwriter wiseass, heavy on keys, crooning, and observational comedy, to answering one particular question: What if a lounge lizard did a residency in a casino on the moon? And the strangest thing about it is that, after listening to the record, you will inevitably find yourself thinking  Yeah. Sure. That question makes sense. There probably would be a taqueria on the roof. He would be hitchhiking around with a monogrammed suitcase. And people would be talking about documentaries a lot.

As Craig Jenkins wrote in his review, Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino resembles nothing from the last few decades of pop music more than Harry NilssonÔÇÖs John LennonÔÇôproduced blotto masterwork Pussy Cats, an album that sounds like two very talented and successful men having a very beautiful and boozy nervous breakdown. That album, and its release date ÔÇö 1974 ÔÇö provide the key to unlocking the unlikely artistic success of Tranquility Base of Hotel and Casino. By applying mid-ÔÇÖ70s style lounge music ÔÇö drunken, broken, wailing, masculine-ego-in-crisis lounge music ÔÇö to the subject of space, Turner has recognized that our conceptions of the final frontier are intrinsically tied to the years when the first, best space movies were being made ÔÇö years that coincided with this kind of music.

Key to grasping this is understanding that space itself has become a retro concept. Human feet havenÔÇÖt touched the surface of the moon since December 1972, and in 1975, the ÔÇ£handshake in spaceÔÇØ marked the end of the space race between the Americans and the Soviets. While outer space has continued to be an area of interest and attention for human minds in the 40 years since then, the burst of creativity and ingenuity that coincided with the height of the Cold War created a palette and a nomenclature that has been added to, but never significantly replaced, by the films that succeeded it. This isnÔÇÖt a dig at the movies that have come since, so much as it is a suggestion that the first examples of a genre tend to define that genreÔÇÖs scope, particularly when theyÔÇÖre based in a genuine historical moment. And, more crucially: WeÔÇÖve been in space since 1975, but we havenÔÇÖt been on the actual moon that whole time. The moon is very 1970s ÔÇö and so are lounge singers, especially the Nilssonian version of them, whacked out on whiskey and acid, screaming their voices hoarse, then sidling up to the piano, taking a deep breath, and singing the loveliest song youÔÇÖve ever heard.

On Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino, Turner takes on a bunch of modern subjects, from binge-watching television (ÔÇ£EverybodyÔÇÖs on a barge, floating down the endless stream of great TV,ÔÇØ from ÔÇ£Star TreatmentÔÇØ) to gentrification (ÔÇ£Cute new places keep on popping up since the exodus, itÔÇÖs all getting gentrified,ÔÇØ from ÔÇ£Four Out of FiveÔÇØ) to politics-as-pro-wrestling (ÔÇ£The leader of the free world reminds you of a wrestler wearing tight golden trunks,ÔÇØ from ÔÇ£Golden TrunksÔÇØ). But mostly, he paints the bizarrely compelling portrait of a man so out of his time that he ends up on the moon, where his piano-and-sunglasses-indoors routine fits in like it came with the place.

The 1960s and 1970s were a time where our culture was attempting to escape, fleeing from the threat of nuclear apocalypse, the expectations of conformity, and then the substance-addled burden of trying to then defy that conformity. We went to the moon, but we also took LSD, and thatÔÇÖs why thereÔÇÖs no more crystalline expression of the era than the Stargate sequence in 2001, which, by combining these two coping mechanisms, causes the film to collapse in on itself.

If Tranquility Base Hotel and Casino seems to be taking a similar approach, then it could be because thereÔÇÖs a comparable desire for escape in the air that Arctic Monkeys are responding to, a parallel notion of trauma and trip walking hand in long-nailed hand. Or maybe Alex Turner just got a piano for his birthday. Either way, space is still the place, the place being 1974. Come and stay with us ÔÇö itÔÇÖs such an easy flight.