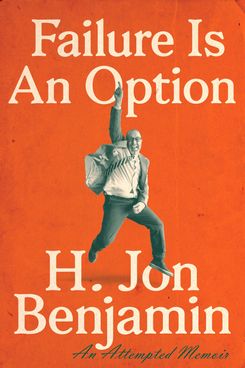

The following is an excerpt from H. Jon BenjaminÔÇÖs new memoir, Failure Is an Option, out today. These days Benjamin is best known for voicing the titular characters on FXXÔÇÖs Archer and FoxÔÇÖs BobÔÇÖs Burgers, but not everything heÔÇÖs worked on has been a success. Below, Benjamin looks back on the spectacular disaster that was Midnight Pajama Jam, the perfect example of how one project ÔÇöwhether itÔÇÖs a late-night talk show for kids, a weekly UCB show, or a recorded DVD ÔÇö can fail on every level.

Not everything in my career has been successful. But sometimes failed endeavors hold the best memories. In comedy, as with everything, there is so much out there, unheeded, left aside, millions of moments just drawn and forgotten. Every piece of comedy, a standÔÇæup set, a homemade sketch, a cartoon drawing, or a notebook of ideas ÔÇö all that which lives on some abandoned corner of the internet or in some cardboard box, it will probably never be seen. ItÔÇÖs what makes it special. ItÔÇÖs a piece of personal history.

Back in the early 2000s, I was in a bit of a rut. I had just had a kid (the shit eater), and I was essentially out of work, except for a few acting roles here and there. At this point, with AmyÔÇÖs help, I came up with a concept for a TV show: a lateÔÇænight talk show for kids called Midnight Pajama Jam. The goal would be to air the show around eight thirty or nine, around the time young kids go to bed, and make it like their version of The Tonight Show, except with absurdist guests.

An artist friend made two puppets, a purple octopus and an eagle, and I tapped comedian Jon Glaser to play the sidekicks ÔÇö except instead of any puppeteering, he would just hold the two puppets up on his fingers and do the voices for both, unconcealed to the audience. The eagle, named Lumpy, had a gravelly tough voice and said ÔÇ£RaaaaaaaahrÔÇØ a lot, and on the index finger of the other hand was the octopus named Scott Fellers, who had an effete accent, like Gore Vidal if he were an interior decorator.

The dynamic was that Lumpy and Scott Fellers disliked each other very much and would openly bicker all the time. As far as guests, we would come up with characters, a mix of random oddballs who would do traditional interview segments, but improvised based on an outline of some particular comedy conceit. It was a bit Pee-weeÔÇÖs PlayhouseÔÇôish, in that it completely ripped off Pee-weeÔÇÖs Playhouse.

We first set out to do a live test of the show in a small theater in Midtown in the afternoon to cater to an audience of mostly kids. We had a house band and three guests. One of the guests was a character called Pit Stain. He was a fictional ÔÇ£neighborÔÇØ who would drop by the show uninvited and tell mundane stories, with his hands always raised behind the back of his head, exposing the namesake pit stains. Next was a segment called ÔÇ£Vanity Plate,ÔÇØ in which two guests who ostensibly had the same vanity plates on their respective cars come on. The plates read hotÔÇæstf; the man had it because he thought he was attractive, and the woman had it because she owned a bakery.

Everything in the show went fairly smooth until we presented a guest called Wyatt Trash, which was a bit where the actor Matt Walsh, dressed in overalls, sang a song with a Southern twang, with lyrics that went as follows . . .

IÔÇÖm Wyatt Trash, IÔÇÖll kick

your ass I fucked your best

friendÔÇÖs wife

Eat a can of beans, drive to New

Orleans, Now IÔÇÖll try and suck my

own dick.

Then, he dove on the floor, and, awkwardly and with great effort, tried to contort his body to give himself oral sex. I donÔÇÖt know how we felt that this was okay, but it was, in retrospect, a glaring oversight, bordering on child abuse.

The upside was that most or all of the kids were too young to decipher what was happening and just laughed hard at a man writhing wildly on a floor without context. The problem was that the parents were not children and understood very clearly the context. So it was a bit of a moral conundrum. In hindsight, it was a show that adults and kids could enjoy together, as long as the kids didnÔÇÖt understand autoÔÇæfellatio.

As we developed the show, we phased out the kid angle and adapted it to be more strictly for adults but kept the puppets and the loose, wacky concept. This involved losing the full band and replacing it with my friend Gary behind a keyboard in a CÔÇæ3PO mask, whoÔÇÖd mimic playing John WilliamsÔÇÖs theme from Star Wars as the CD was played over the sound system. We would still bring out fake guests with different comedy concepts and kept the improvisational nature of the show.

The odd thing about a failed venture is that, while youÔÇÖre working on it, you have no idea itÔÇÖs failing. I think we all thought at the time that we were on the cusp of something. At the onset, the show was exciting to do, despite audiences that topped off at about ten. When there are more people in the cast than in the audience, it makes for an odd dynamic.

We initially performed the show at midnight at the original UCB Theatre in New York City. The first show there had about eight people in the audience, and our guest musical act was the Trachtenburg Family Slideshow Players, who were a real family musical group (mother, father, and daughter) who wrote songs based on slides they found at estate sales, which they projected behind them when they sang. The daughter, who played drums, was around eight. Gary, our CÔÇæ3POÔÇæmasked bandleader, had taken acid that first night and got it in his head that the mother and the father were holding the daughter captive and making her play drums against her will, so during their performance, he tried to stop them by sticking his head through the curtain and trying to get the daughterÔÇÖs attention so he could free her from playing. Fortunately, he never ran out and grabbed her. I guess even on acid, he was respectful of boundaries.

When we started to do the show weekly, we performed it at the UCB Theatre in Chelsea, right around the time it moved there from its original location. That theater had about one hundred seats and had taken over the space from a small repertory theater. The most interesting shows were the ones where the audience (for our show) was split between a smattering of friends and then a few older couples who thought theyÔÇÖd be seeing a show staged by the previous repertory theater and never checked that the theater had changed to an improv comedy venue. IÔÇÖm not certain which I enjoyed more: the disdain from childrenÔÇÖs parents or the disdain from confused old folks wondering why they were seeing Wyatt Trash and not Hedda Gabler. Although there were parallel Freudian themes.

As we kept doing the show, our audience didnÔÇÖt exactly swell. It more just smoldered. Typically, with this kind of project, you see some returns for your efforts, as word of mouth would start to spread and audiences would start growing in size. And IÔÇÖm not saying there wasnÔÇÖt incremental progress, but on the whole, most shows were not well attended. But this wasnÔÇÖt exactly unfamiliar territory. Once, when I was in a sketch troupe in Boston called Cross Comedy, we came to New York City to do a run at a small theater in a Midtown black box theater, and the first showÔÇÖs audience consisted solely of my aunt. Literally, only my very Jewish aunt Marion, sitting at a frontÔÇærow table basically touching the stage. The rest of the room was empty.

We noticed this only moments before the show because we were all in the green room, and then one of the members of the group went to check out the crowd and returned to say, ÔÇ£You all will want to see this.ÔÇØ When we discovered the empty theater but for the older woman in the front, and I recognized that older woman as my aunt Marion, I begged them to consider canceling, but we were rehearsing for an industry show (to present to television executives) so the rest of the group insisted on doing it. The comedian Dave Attell was the warmÔÇæup act, and he had to go out and do ten minutes of standÔÇæup exclusively for my aunt, who, by the time we started our show, was eating a Reuben sandwich with a glass of red wine at her table.

After the show, she said stolidly, in her very Jewish voice, ÔÇ£I liked the comedian.ÔÇØ So not only did we just perÔÇæ form only for my aunt, but she ended up not even liking it. So yes: IÔÇÖd had some experience with dismally attended shows.

Sometimes, in comedy or any other endeavor selfÔÇæ promoted and selfÔÇæsustained, just sticking around is half the battle. So many unbelievably funny people dropped out of doing comedy, simply because itÔÇÖs a zeroÔÇæsum game at a certain point. I just happened to be lazy enough to not get out of it. Basically, I hung around long enough.

But Midnight Pajama Jam was wearing out its welcome, so Jon Glaser and I did the natural thing and decided to gather enough money to make a DVD despite strong public disinterest. It was like the Producers scheme except everybody, including us, would lose money. I got donations from friends and family, and we staged a show taped at a small theater called the Marquis in downtown NYC. The show went well. We had Matt Walsh back as Wyatt Trash. The comedy duo Slovin and Allen came on portraying two fundamentalist pastors who travel the country warning kids of the evils of pornography from the back of a van. Also, Eugene Mirman came on dressed in period costume as a ÔÇ£gayhunter,ÔÇØ in the spirit of Van Helsing, but instead of vampires, he hunted gay people. Also, comedian Sam Seder, who happened to have really huge and muscular calves in real life, held up a curtain, with his back to the audience, and set a spotlight toward the bottom of it and, as music came on, raised the curtain to reveal his oiledÔÇædown calves, like some fetish striptease. If nothing else, we finally captured the essence of a show that we had worked on for the better part of three years. It was a bit of a mess, but it was a creative, ambitious mess. And the taping gave us hope that we could sell the show to television so we could get a bigger audience on board. That would pay back our small investors (my sister, Jodi) and put us in a position to achieve bigger goals.

We couldnÔÇÖt wait to get to editing the footage we had.

In fact, our editor Bill Buckendorf called the next day and told me to come over to his apartment as soon as I could. Apparently, he was as excited as I was to get this show together. Bill did all the videos for Midnight Pajama Jam. He lived in the East Village on St. MarkÔÇÖs in a sixÔÇæ story walkÔÇæup, so I was never excited to go over there to edit, but knowing we had done a good show overshadowed my hatred of climbing six flights of stairs.

I got there and sat down at his desk in his small bedÔÇæ room, where he edited. He looked a bit sheepish, as if something was wrong. I asked if he was all right. He gestured to the monitor and said that I ÔÇ£should see for myself.ÔÇØ He played down the raw footage of the showÔÇÖs opening and there was no sound, so I told him to turn it up.

He said, ÔÇ£It is up. ThereÔÇÖs no sound.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£On the whole thing?ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£No, not the whole thing.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Oh, thank God.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£The sound kicks in at the very end.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£At the very end of all the footage?!ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Yeah.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£FUCK!ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£I think the sound guy forgot to press record until the very end of the show.ÔÇØ

After all this, our record of the Midnight Pajama Jam show is basically a silent movie until I come out to say good night to the audience. I suppose it was a poetic climax to a show that maybe was never meant to be, and a testament to the idea that some of the best memories are the times leading up to the grandest failures. IÔÇÖm sure thatÔÇÖs how the guys at Enron felt, but, in our case, all we did along the way was lose money. We were poor but happy. Well, not exactly happy.

From FAILURE IS AN OPTION by H. Jon Benjamin, published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright ┬® 2018 by Hosenfef, Inc.