Tom Wolfe, one of the great observers of the American scene — not least in his unique and peerless work at New York Magazine — died yesterday at 88, the Times has confirmed.

As a journalist and novelist, Tom Wolfe could, like no one else, take one particular broad subject — class and status — and slice it thin for examination and diagnosis, like a pathologist with a microtome. (Many people still don’t think America has a class system. He knew better.) He seemed to love nothing more in print than to identify precisely the striated signifiers that communicate prestige, and do it in prose that danced and skipped along irresistibly as he did it. Wolfe had been an American Studies student at Yale, and — to use a favored expression of his — Santa Barranza! did he study America.

He got to begin that journalistic study at the best possible perch. In 1962, Wolfe was hired by the old New York Herald Tribune just as its editors and contributors were attempting to save their dying paper. Part of the push was to produce a serious daily that was far more stylishly written than the New York Times. (It was an achievable task: Most of the Times’ prose of that era was pretty joyless.) Two Trib writers — Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin — were pulled toward the Sunday-magazine section of the paper, which was being reimagined and renamed New York under the editors Jim Bellows and Sheldon Zalaznick, and (after Zalaznick was promoted a few weeks into the job) they were soon joined by a Time-Life alumnus named Clay Felker. Wolfe wrote for Felker frequently and hilariously, starting with a 1,500-word column each week, about New York rudeness, about the clothes he saw in the supermarkets of the Long Island suburbs, about the loopiness of landlord-tenant battles. He was doing similar, longer work on the side for Esquire, including the profile of a group of car customizers that became the title essay of his first book.

The term everyone throws around for this kind of writing is “the New Journalism.” It’s a misleading one, because it wasn’t new. Joseph Mitchell, John Hersey — heck, Nellie Bly, 80 years earlier — all had done similarly immersive reporting. But there was something new about this, in its energy and its connection to the moment, and in the tonal shift that came with a new generation’s interests and habits. Wolfe and Breslin and Gay Talese and Joan Didion and Nora Ephron were onto something, in the pages of New York and Esquire and a few other outlets: that vivid scenes and acute social observation and awareness of the journalist’s presence could tell the truth in ways that had infrequently taken place outside the world of fiction. Virtually every journalist working today, to varying degrees, has absorbed that lesson. Nobody — and Santa Barranza! I mean nobody — writes or even punctuates like Tom Wolfe, but a lot of us try to look at things the way Tom Wolfe did.

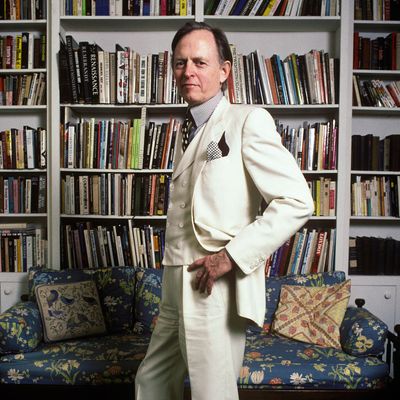

He became known as a man-about-town for his elaborately hand-tailored clothes, including, of course, those white suits — such a perfect metaphor for the detached journalistic observer in a sooty, grimy city. (What does wearing a white suit require? That you stand aside and take notes, that you look but not touch.) His on-page manner depended on ridiculously long sentences, sometimes depending on the heavy use of … ellipses … and more ellipses … and complex punctuation like :::::. He was probably the first postmodernist on a major metro daily, co-opting some of the prolix habits of high 19th-century style — repurposed with winks and detached irony. (Look at a few of the weak Wolfe parodies that are out there, and you’ll see just how hard it is to write that way without being silly.) And in 1965, he and Felker, in the Tribune, happened upon an idea that was irresistible.

The New Yorker was turning 40, occasioning a certain amount of “greatest magazine that ever was” praise. Despite that, and despite the presence of a few of those New Journalism proto-pioneers, it was going through what was arguably one of the duller stretches in its history. Wolfe decided to try (in a move that Spy and Gawker, among others, would later make a raison d’être) putting into print what most journalists would say only at the bar after hours.

The manuscript he produced was so long that it had to run in two parts. “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of The Ruler of 43d Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!” was the first half, published on April 11, 1965, and it was vicious, hilarious, punishing, gleeful. Its basic stance was, as Wolfe himself said, to paint a portrait of “a room full of very proper people who had gone to sleep standing up, talking to themselves.” Yes, it was a little bit mean. It was also deadly accurate, and, probably inevitably, became the most-talked-about story in newsrooms across the city. (Old trick: Write about the press, and everyone in the press will write about you.) William Shawn, the magazine’s tiny-mummy-in-chief, was horrified, to such an extent that he attempted to get the Trib to discard the second installment instead of publishing it. (He did not succeed.) Dozens of the magazine’s writers, even J.D. Salinger, signed a letter of protest to the owner of the Trib. It’s been suggested here and there that Shawn really did take the criticism to heart, also that the majestic “In Cold Blood,” the robust story by Truman Capote of two thrill-killers that he published a few months later, was perhaps a silent answer to Wolfe’s wake-up call. How dare you call us sleepy? Here’s the best true-crime story you’ll ever read. And Capote’s subsequent book was often called a “nonfiction novel,” a tacit admission that the novelistic techniques of New Journalism were indeed part of The New Yorker.

When the Trib (and its short-lived successor paper, the World Journal Tribune) died for good in 1967, Felker and his colleague Milton Glaser began planning to relaunch their magazine on its own, and began raising funds and building buzz. They were able to do so partly on the strength of their three marquee writers: Gloria Steinem, Jimmy Breslin, and Wolfe. When the magazine reappeared as a glossy in the first week of April 1968, the three of them appeared in the first issue, Wolfe with an essay called “How to Tell If You’re Wonk or Honk,” about New York accents. His eye for class and social distinction had found its perfect outlet.

Over the next couple of years, Wolfe began to write longer, at a slower frequency, as the magazine found its way and figured out its collective voice. And if there was a story that coalesced it all, it was Wolfe’s “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” published in June 1970, about a fundraiser at Leonard Bernstein’s apartment for the Black Panthers. It had everything a journalist could ask for: celebrity, a near-comical clash of cultures, elements of racial conflict, extreme timeliness, and rich people acting a little absurd. You can read it here, and should. It’ll be taught as long as there are journalism schools. As will “The Me Decade,” the story that named the 1970s. It’s an extremely unusual piece of magazine writing, going off into thickets about the sociology of Max Weber, but it’s under control all the way, and you will not find a better summary of the baby-boomer solipsism that (one could argue, and Wolfe does indeed suggest) was beginning to eat America alive.

Wolfe (and Felker and Glaser) left New York at the beginning of 1977, after the magazine was sold, and from then on his magazine work was mostly at Harper’s and Rolling Stone. At the latter, he began a project telling the true story of the American space program and the early test-pilot and astronaut corps. The Right Stuff, published serially in Rolling Stone and in book form in 1979, is by far the longest of all of Wolfe’s journalistic projects, and probably his best. In many ways, it is really a fast-moving history of alpha males in postwar America: about the Cold War, faith in technology to fix things, men behaving badly, men behaving honorably, the role of science, the role of the press, and far more.

It is a masterpiece. (You should also watch the movie, which tanked on release but is much better than people remember.) It nearly broke him, too: Its publication was first announced the year after the first 1969 moon landing, and it took him ten years to get it done.

It’s a novelistic book, so it is not especially surprising that Wolfe subsequently got into the business of writing fiction. And, as he rather assertively pointed out in a notorious essay for Harper’s, and then a follow-up some years later, he believed in reported fiction, shot through with field research and Whartonian social observation. His first novel was written serially for Rolling Stone — it’s been said that his editors white-knuckled it through every installment’s press deadline — but it was worth the wait to them. Bonfire of the Vanities was and is the novel of New York in the Greed Decade.

Wolfe spent most of the remainder of his life as a novelist, with only occasional bits of pure journalistic writing. His final book, Back to Blood, was published in 2012. My colleague Boris Kachka wrote about him, superbly, on that occasion. But New York did coax Wolfe himself out of semiretirement last year to write about the photographer Marie Cosindas, an old friend who had just died at 93. Cosindas had spent much of her career producing unusual color photographs, in an extremely painterly style. “When she died last month,” Wolfe wrote, “she was one of America’s leading art photographers — or was it leading classical painters? You could choose either one, or both, and not be wrong.” The reporter-novelist understood: It’s all one thing, balled up, craftsmanship and art-making and just plain paying attention. The great eye took it all in.