There’s a truism that’s been making the rounds for a while now, an idea that TV ignores working-class families. There is a sea of TV series about families whose problems skim the surface of financial reality, stories about people who are oblivious to amorphous, inescapable class anxieties in the way that only comfortably middle- and upper-middle-class families can be oblivious. And in the midst of that expanse, much of the response to the Roseanne revival, which ends its tenth season next week, has made the show seem like a singular, stand-alone boulder that’s been plunked into TV’s otherwise comfortable, wealthy waters. That truism is based on truth. There are not enough television shows about working-class families and people with blue-collar jobs. There are not enough sitcoms that focus on retail employees, or young people with college educations and no way to pay for their own housing. There are not enough sitcoms about families with lower-level white-collar jobs who still can’t pay for health care.

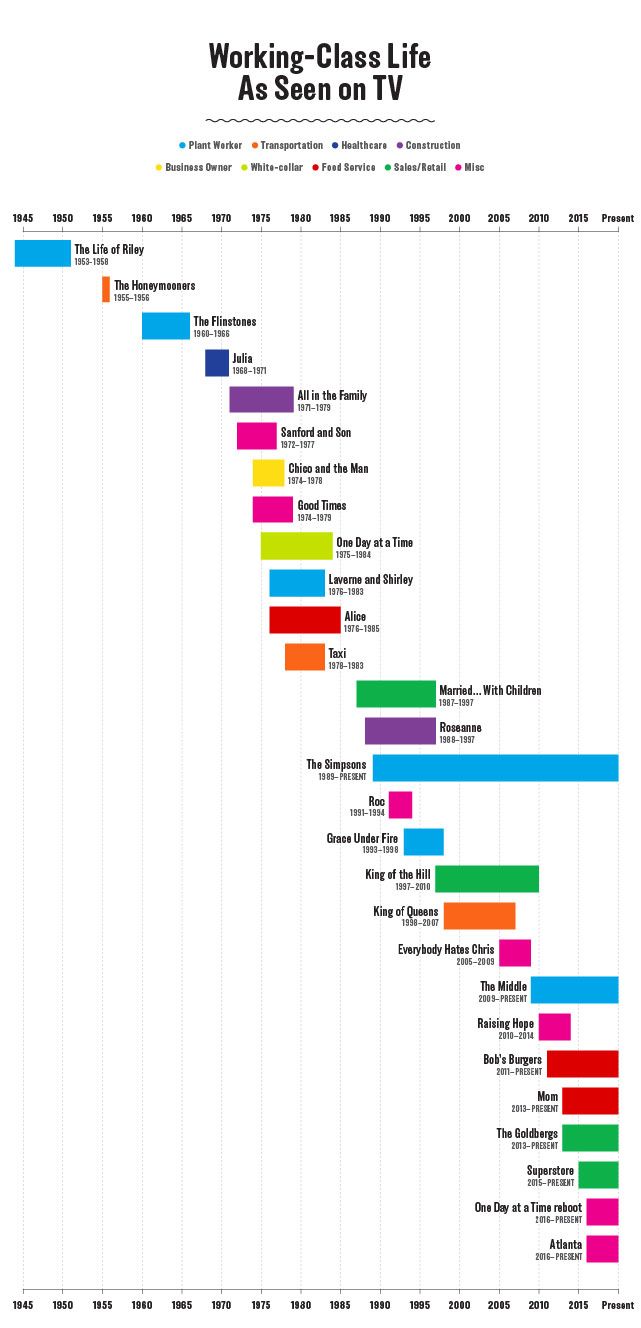

“Not enough” is not the same as “none,” though. Roseanne is part of a lineage of TV-sitcom families, stretching back through a Norman Lear–centric boom in the ’70s and reaching all the way to some of the earliest TV shows with characters imported from radio serials. And just as importantly, it joins a too-small but existing cohort of TV shows about what it’s like to live on the edge of not having enough, to drive a car with plastic wrap taped over where a windshield would be, and to sneak food into a movie theater in order to save money. Inspired by this timeline of families of color on television, this list of working-class TV sitcoms is an effort to sketch out a history of how TV has depicted working-poor and lower-middle-class families since the beginning of the medium.

This timeline is not exhaustive. It doesn’t include a number of sitcoms that only appeared for a handful of episodes, and it also ignores many series that are ostensibly about working-class characters but which avoid any meaningful grounding in financial realities or class-based anxieties. Thus, no According to Jim, or 2 Broke Girls, or even the one-season show actually titled Working Class. But the list is deliberately a little stretchy, in terms of both “sitcom” and how we think about the working-class individual; it’s a collection of shows that represent a range of what financial insecurity and class pressure look like in TV comedies. The list swerves outside of a strictly “blue collar” designation to include shows like Julia (a sitcom about a single, widowed mother who’s a nurse that was both groundbreaking and criticized for being unrealistically cheery), and Bob’s Burgers, a show about a restaurant owner, and also Atlanta, a series about hustle and striving that’s not precisely a sitcom, but is absolutely a vital representation of work and American life shaped by uncertain financial futures. (The list represents changes in depictions of the working class, but also in the genre stability of the comedy on TV.)

This list is a curated collection, so I’m not going to claim that it shows quantifiable, definitive trends. But it’s worth noting the relative dearth of big, buzzy shows that fit into this mold in the 1960s (Fred Flintstone works in a quarry, but The Flintstones is not a gritty, realistic depiction of the working-class grind) and the similar gap in the ’80s. It’s maybe even more interesting for what it suggests about the qualitative drift in what a popular working-class sitcom could look like. The Life of Riley takes its name from a phrase that means a life of comfort and ease, and although the show gives its titular Riley all kinds of minor financial obstacles and class anxieties, there’s never any sense that the wolf is really at the door. Riley would like his daughter to marry a “college man,” but his family will not starve. By the time the original Roseanne rolled around, though, the popular depiction of a working-class, blue-collar family included a mother coaching her son on how to give bill collectors the runaround.

One point to consider: how few of these sitcoms are about work, first and foremost. There are some exceptions: shows like Taxi, Chico and the Man, and Superstore make the workplace the primary setting and use co-workers as the stand-in family unit. Laverne and Shirley are roommates, and they also work together as bottle cappers at a brewery. But most workplace sitcoms are either decidedly middle- or upper-middle class (30 Rock, Parks and Rec, Murphy Brown, NewsRadio, Mary Tyler Moore), or they gesture at class while eliding money.

It’s probably unsurprising, given our national discomfort with open conversations about salaries and compensation, that the default fictional space for working out ideas of class and money and financial insecurity isn’t the workplace. It’s the home, where the pressure of uncertainty and the desire for security get filtered into stories like Ralph Kramden’s perpetual, ill-fated schemes to get rich on The Honeymooners, or Grace’s $80 rent increase leading to a chain of child-care rearrangements on Grace Under Fire. Work happens at work, but on TV at least, money and class are conflicts that usually take shape in the home.

Finally, while it would be amazing if the popularity of the Roseanne revival leads to a wave of new series that focus on working-class characters, it’d be even better if they did not all look like (or work like) the Conners. Very few of these series are about people without children. Very few of them are about families of color. Given trends in the duration of employment, working-class shows should probably have more stories about changing jobs. And in the history of working-class families depicted on television, most fictional families have looked like the Conners: white, blue-collar, heterosexual married couples with children. There’s little question that the future of the genre will continue to include them. The hope is that the working-class sitcom will start to make more space for everyone else, as well.