Kanye West is hip-hop’s Erik Killmonger. The villain from the Black Panther film and comics is magnetic, articulate, and frequently successful. He seeks and finds power because he’s driven and talented, but also because he craves the approval of a country that doesn’t seem to want him, even though he holds that country directly responsible for tragedy in his family. In Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther adaptation, the character is a pro-black cad whose ideas about revolution tend to elevate him at the expense of the safety of his subjects and the honor of women in his power circle. All of this sounds like a tight synopsis of the last five years of Kanye. The rapper-producer-designer is a thought leader frequently acknowledged for risky statements and prickly politics but also challenged for solipsism and chauvinism.

Since the summer of Yeezus and the confrontational press meets that followed, West’s ideas about black liberation have often been centered around blockages hindering his own personal gain as a maker of sneakers and outerwear with dreams of designing furniture and more. (Yeezus is, spiritually, every bit of the smug, walled-off Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous record people complained that Watch the Throne was. Say what you will about the Jay album, but at least its social consciousness stretched beyond the fingertips of the people who created it.) His budding friendships with politicians and pundits whose policies jeopardize the health and prosperity of people of color present a shocking turn for an artist who once warned that, “The prettiest people do the ugliest things / For the road to riches and diamond rings.”

That lyric from the poem that became The College Dropout single “All Falls Down” was prophetic. Kanye West’s music has grown incrementally darker and lustier ever since. Songs like My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy’s “Hell of a Life” — a carnal daydream that is equal parts Black Sabbath and Heavy Metal — used to be outliers in his catalogue, but across Yeezus and The Life of Pablo, they became the meat of the work. On Yeezus, West’s philanderer’s dreams seemed animated by cold feet, or at least first-time dad jitters. But by The Life of Pablo, the stakes were much higher: “30 Hours” described a morning routine that involved checking gossip blogs to see which of his antics from the night before had been recorded, and “No More Parties in LA” treated a freeway speed limit like a dare. The album’s dire religiosity seemed like a cry for help. The pages of TMZ headlines that followed are harrowing proof he meant business.

Two years after Pablo, Kanye’s new Ye album offers fresh insight into the artist’s rocky travels. If the lyrics are to be believed, the months he took off press and public appearances last year don’t seem to have won him much peace. Track one opens with a monologue pondering if not death, then suicide, depending on the answer to the question of who is hearing West say, “I thought about killing you.” These songs gush about psychedelics, prescription drugs, and extramarital affairs, then they fret over what Kim Kardashian-West will make of all of it. “I think Prince and Mike is trying to warn me,” a song appropriately titled “Yikes” theorizes. “They know I got demons all on me.” “Ghost Town” includes a pledge not to “bet it all on a pack of fentanyl.” Delivering the line over a beat that jams organ swells from Vanilla Fudge’s “Take Me for a Little While” together with vocals from Shirley Ann Lee’s wistful gospel tune “Someday” is a dizzying trick. The producer’s expert handle on sounds and samples lends the message extra gravity.

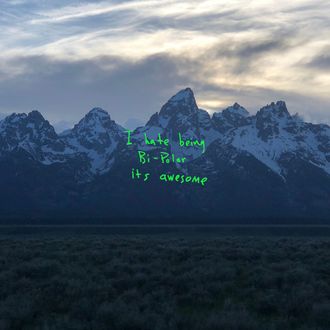

This is pretty music on the surface, but beguilingly so. Ye is sweet but haunting in the way that Elliott Smith songs are rich in melody but also chillingly stark. This is the quietest album in the entire Kanye West catalogue. Emptiness is a fascinating new direction for an artist known to jam a dozen voices into a single record. “Wouldn’t Leave” makes the most of twinkling bass and keys and sanctified shouts on loan from Reverend W.A. Donaldson’s “Baptizing Scene.” The club jam “All Mine” sounds like a reggae riddim scrubbed of half its contents. “No Mistakes” sweeps from a booming Charlie Wilson chorus to a section of spectral bass and diced Slick Rick lines that effect the same sense of late-night mischief as old Black Moon records. It’s no wonder the listening party for the record took place on breathtaking ranch lands in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Ye does a keener job of conjuring the thick quietude and wide-open spaces of the American wilderness than the guy who disappeared to Montana and came back this winter with an album called Man of the Woods.

What the new music doesn’t do so well is process the strife that birthed it. In an interview at the Wyoming party with Atlanta radio host Big Boy, West said that Ye was going to be an overtly political album until he “completely redid” it in the wake of his damaging TMZ appearance last month. If lyrics were torched in order to address that stuff, then “Wouldn’t Leave” is the only track that excels at the work. The first verse describes the TMZ gaffe as more than just a crisis of public opinion but rather a moment where husband and wife panicked and briefly considered a separation. The chorus line — “I know you wouldn’t leave” — is a strange anchor for a “stay with me” song in the same way “No Mistakes” is an offbeat “girl I still love you” song. Sandwiched between the massive choruses of the latter is a lengthy, passive-aggressive shot at Drake (“Too close to snipe you / Truth’s told, I like you”) where you might expect words for Kim. The messaging is questionable. It feels like these words were written before West got the chance to really turn the last month’s events over in his head, but he ultimately skirted catastrophe in leaning into his natural knack for apology.

Ye’s most affecting moments find West realizing he might be tarnishing his gift and legacy but also straining to hit the brakes. “Yikes” advises listeners struggling with mental-health matters to seek help because “shit could get menacing” but spends its verses delightfully cataloguing past self-destructive behavior. “Ghost Town” is a tearful trip back to the well of soulful penitence that spawned “Runaway.” (The new song floats where it should soar for sounding more freestyled than written.) Kanye is an effective vessel for this kind of song because, to quote Miles Davis, “he’s got that church thing up in what he does.” West owes much to sample whizzes like J. Dilla and RZA in that his true gift is making old soul and gospel records sing where words fail him. As was the case with Yeezus and The Life of Pablo, Ye seeks redemption via altar call. But the raps here are much too sweet on CIA-grade psychotropic drugs and sex with women other than Kim for the apologies on the back end of the record to carry as much weight. Forgiveness is love on loan; you pay it back by righting your wrongs. Ye talks the game. Is Kanye living it?

At the end of Coogler’s Panther, Erik Killmonger is mortally wounded in battle with his nemesis T’Challa and famously refuses the Wakandan king’s merciful offer of absolution. “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships,” he says, scowling in the dying light of the African sunset. “They knew death was better than bondage.” Kanye West is a man with a hundred obligations whose idea of freedom is sliding responsibility off the table, whose concept of free speech is that he gets to say whatever he likes without consequence. America keeps serving sharp rejoinders to both notions, and Kanye keeps finding ways to win everyone back. Ye is different because this time, he’s not sorry for the infractions people are maddest about; what’s an apology tour without the apology?

You want to believe in brash, charismatic people because we are all uplifted by their successes. You watch yourself around them because their failures carry the same pull. Kanye West was once the everyman’s rapper, a poet of the downtrodden. He hasn’t been that artist in years; it’s funny that it took this long for him to make a self-titled album because the primary subject of his music has been himself for the better part of the decade. This doesn’t rob his music of value, and the quality of Ye, just in terms of the chunky, delicious sounds of the synths suggests there’s hope left for the man who created it. But the flawed ideas and rushed execution are proof that it needed to bake longer. Ye is a bit of a success and a bit of a failure. Like a collapsed, undercooked cake, it’s temptingly sweet but also disconcertingly mishandled. “The most beautiful thoughts are always beside the darkest.”