If you take him at his word, Drake is hip-hop’s James Bond: suave, rich, clever, vengeful, mercenary, and effective. He thinks things through to their logical conclusions before they get there. That lands him steps ahead of the competition. He knew that Meek Mill didn’t have a plan past Twitter rage in 2015; the swift, brutal two-hit combo of “Charged Up” and “Back to Back” netted the Toronto rapper a king’s ransom in tough-guy cachet. He needs that stuff because he doesn’t have street bona fides he can hang back from the comfort of a mansion and reminisce about for 20 years, like a lot of his elders do. He’s had to scratch and fight for the respect of the public. And respect isn’t some tangible commodity you can grab up and hoard, like an art collector. Actions and apprehensions affect the value of a person’s platform in real time, like stocks. Building a formidable profile is precarious; falling back to square one’s a cinch.

This year has been Drake’s most concerted — and for the most part, successful — push for unilateral love. He made everyone cry giving stacks of cash and misty-eyed hugs to families in need in the video for “God’s Plan.” Then “Nice for What” turned Lauryn Hill’s “Ex-Factor” into a bounce anthem and used the accompanying visuals to celebrate a baker’s dozen of talented black, white, and brown women in Hollywood. Both singles shot to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, and stayed there collectively for months. Guest appearances on songs by the southern rap acts Blocboy JB, the Migos, and Lil Baby rounded out the top ten. It was a rare convergence; not even Taylor Swift, a pop tactician successful enough for UPS and ESPN partnerships, hits the top ten more than two or three times in a year. It seemed perfectly plausible that Drake’s best work was on the horizon. Then he got greedy.

By all outward appearance, the cold war between the Clipse and Cash Money, one of rap’s longest and most confusing tiffs, started as a row over who wore the streetwear brand A Bathing Ape first in 2006. Skirmishes between both camps have broken out every year since. Drake came to Cash Money as an enthusiastic fan of the Clipse but quickly found himself inheriting static with one of his rap heroes. For years, Drake and Pusha-T ribbed each other for sport: Snaps on Push’s “Exodus 23:1” begat snaps on Drake’s “Tuscan Leather,” which begat snaps on Push’s “Suicide,” etc. When Pusha closed out May’s Daytona with “Infrared,” which rebuffed questions about his street cred in Drake’s “Two Birds, One Stone” with ghostwriter jokes and darts about the failing relationship between Birdman and Lil Wayne, the Toronto star jumped at the chance to go headhunting.

“Duppy Freestyle,” Drake’s prompt, rude “Infrared” response, took the exhausted, annoyed tone of someone killing a bug, or taking out the trash. But “Infrared” was a feint, an attack seemingly waged with the express purpose of drawing the opponent into a position where a much bloodier battle could take place. The blistering, personal meanness of “The Story of Adidon” and the shaky days that followed — where Drake defended his past use of blackface, dropped a Degrassi-themed video for the iffy single “I’m Upset,” and got tagged out of the fight by the Texas rap legend J. Prince — broke the perfect peace of the rapper’s landmark year. These weren’t the unfazed moves of a champion. This was someone flustered and buying time to plot.

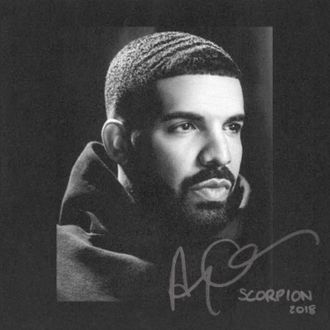

Scorpion is an album (his fifth) about losing, about coming to the realization that missteps, like chips and gouges in wood furniture, can be buffed and treated but never quite erased. “Survival” opens the project with memories of old rap battles and fistfights: “I’ve had real Philly niggas try to write my ending… / I’ve had scuffles with Bad Boys that wasn’t pretending.” Drake’s tired but not discouraged: “The crown is broken in pieces, but there’s more in my possession.” Over 25 songs, Scorpion attempts to address Drake’s flaws while massaging his bruised ego. A rapper less suited to this specific blend of regretful introspection and flamboyant passive-aggression might have a tougher time at it, but Drake, the maker of “Used To” (“Every time they talking, it’s behind your back / Gotta learn to line ‘em up and then attack”), “Madiba Riddim” (“I cannot tell who is my friend!”), and “4pm in Calabasas” (“I got people showing how much they truly resent me / They whole demeanor just spells envy, they trying to tempt me”) thrives under such circumstances. Across the jilted, scabrous side A and the sweeter, more reflective side B, Scorpion makes cases for Drake as the best and most hated hitmaker in rap and R&B.

Side A is a succession of angry, honest songs of spite and personal revelation. “Emotionless” uses the church-like melisma of early Mariah Carey to own up to allegations that Drake has a son he never talks about: “I wasn’t hiding my kid from the world, I was hiding the world from my kid.” “Sandra’s Rose” salutes the rapper’s mother, a former florist, and fires off a Hallmark-ready line about fate: “I’m the chosen one, flowers never pick themselves.” “Is There More” is a gutting “what’s it all about?” moment in the spirit of the great, sad Drake tracks like “Lose You”: “Is there more to life than digits and banking accounts? / Is there more to life than saying I figured it out?” Side A’s stunning highs are offset by frustrating boilerplate and borrowed flows. “Mob Ties” rips Young Thug off so effectively that his absence from the song’s credits is a shock. The rubbery beat and fun-house ad-libs of “Nonstop” sound like a Playboi Carti song on a Klonopin. When pressed about the matter, Drake once admitted that he treats other people’s flows the way dancehall artists do; he borrows sounds, and sometimes he stumbles on a bigger hit than the original. But in rap, a knockoff is a knockoff.

In many ways, side B is the full-fledged R&B project Drake has been threatening since the lull between Thank Me Later and Take Care, when he covered TLC and workshopped tracks with Mary J. Blige, Chris Brown, and Jamie Foxx. B’s full of songs that pine for partnerships that weren’t built to last; as such, it’s hungry but petty. “That’s How You Feel” is convinced that people go on vacation just to throw it in friends’ faces. “Jaded” accuses a young, unnamed star of glomming on for exposure, then balks at the idea that she dated someone less famous afterward. There’s more than a whiff of toxicity to all of this yearning for situations that ended badly and lovers that brought out your worst that’s not as easy to notice when there’s just half a dozen of them sprinkled across 20 tracks. As is the case with Rae Sremmurd’s 27-song triple album SR3MM, prying the raps off the R&B songs reveals how much both sides need each other.

The best of the mood music that comprises the second half of Scorpion leans into the performer’s strengths, which are a voice that sinks into shoegaze-y synths as subtly and effortlessly as his secret-weapon producer friend Noah “40” Shebib’s aqueous sounds fill any room they’re playing in. The best side B tracks double as good ambient music; strip the drums and vocals off “Jaded,” and the hissing, rolling two-note melody sounds like Stars of the Lid. “Finesse” evokes the dark organ drones of Tim Hecker’s Ravedeath, 1972. “Blue Tint” and “That’s How You Feel” sound like the otherworldly “pyoom” of a laser in a movie about intergalactic warfare. It’s a vibe established in the album’s prerelease trailer — which samples German electronic group Moderat’s song “The Mark,” featured prominently in the movie Annihilation — that could’ve been a weird new direction for OVO if it hadn’t been relegated to the non-singles in the album’s deep end.

But Scorpion is not an album about taking chances. It’s massive, but its scope is narrow. It ditches the global pulse of More Life and Views. There’s not a single foray into grime or dancehall or Afrobeats. Its obsessions are trap, boom bap, and old-school R&B. The big rap guest is Jay-Z. (This is a coup of its own when you consider the snark about fondue and fine art that has passed between the two in the last five years, but the decision tracks when you realize that, once, Jay lost a little respect in a dustup with another rapper and bounced back with 25 songs when really only 18 were needed.) There are vocals from Michael Jackson and Static Major and interpolations of Aaliyah and D’Angelo. Obsessions with singers from the past suit the reminiscences of failed relationships on side B rather well, but pair the mannered ’80s and ’90s soul fixations of the back half of the album with the apprehensive mix of nods to new rap and growling Drake-featuring-Drake bops on the front, and you get an artist at a crossroads.

Over the last decade, Drake, 40, Oliver El-Khatib, Boi-1da, T-Minus, PartyNextDoor, and all of the usual OVO suspects have created a sound that’s big and warm and special to a lot of people. The craft has been refined over the years, especially on Drake’s end. He’s a fighter who pushes himself to such an extent that playing to his old music feels like cuing up old Dragon Ball Z episodes and watching Goku stress over moves he can nail in a flash now. Drake’s powers have grown, but Scorpion is a retrenchment. He’s saving face, keeping up appearances he doesn’t have to, when this album’s blockbuster sales were set in stone months ago thanks to its singles’ streaming success. He’s fussing over people he told us he doesn’t have to answer to. He’s addressing personal matters he said were none of our business. Drake is bothered, but that’s usable energy.

The difference between the good and bad tracks on Scorpion is the difference between venting and ranting, between exorcising bad thoughts and stewing in them. “In My Feelings,” where Drake checks in on new and old friends to see if they’re still down, is the former. “God’s Plan,” where he celebrates the broskis and shades naysayers is the same. As are “Emotionless” and “March 14,” where the artist opens up about the shock of unexpected new fatherhood and laments re-creating his parents’ difficulties in getting along with the mother of his son. All the talk on side A about evil acts he thought about visiting on haters is bunk because he’d never do it. Like J. Prince said, it’s not in his character. There is nothing wrong with that. There’s too much shooting and stabbing in rap. Side B’s obsessions over who dumped him and why are the same concerns he had ten years ago. Seeking comfort in people who failed you is not growth. Both sides of Scorpion needed to drop three or four songs and get a grip. Is Drake turning into one of those 30-somethings who dates people seven to ten years their junior but can’t grasp that they want different things out of life? Is he stagnating, or is Drake’s idea of who needs a Drake, of what a Drake should be versus what he could be, too set in stone? Is there more?

*A version of this article appears in the July 9, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!