This piece was originally published on August 31, 2017. We’re re-publishing it in light of XXXTentacion’s death.

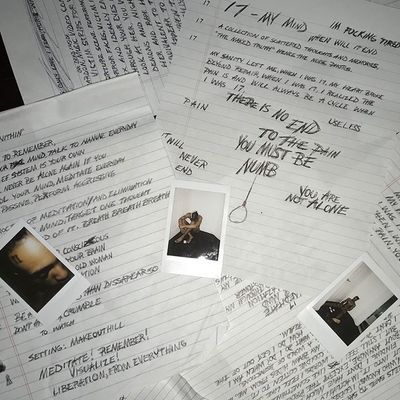

There’s a song near the end of rising South Florida rapper XXXTentacion’s just-released 17 called “Carry On,” where the 11-track mini-album — a ramshackle mix of half-conceived folk musings and confessional depression raps — drops both its amateurish singer-songwriter contrivances and conventional hip-hop rhyme patterns in favor of raw emotion: “Trapped in a concept, falsely accused, was used and misled / Bitch, I’m hoping you fucking rest in peace.” It’s more than just your average jilted breakup rap. The person XXXTentacion is talking about is an ex-girlfriend who accused the rapper, born Jahseh Onfroy, of punching, kicking, strangling, and imprisoning her while she was pregnant, charges he will stand trial for this fall. In spite of those allegations, and an interview on BMX star Adam22’s “No Jumper” show in which he detailed beating a gay juvenile detention center cellmate half to death and smearing the blood on his face because he caught the kid glaring, the rapper was recently selected for XXL’s 2017 Freshman List, which celebrates young hip-hop talent poised for superstardom. (Past honorees include J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar, and Chance the Rapper.) 17 is presently on pace to bow out shockingly close to the top of this week’s Billboard 200 chart.

While he sat in prison for the domestic-battery charge last year, XXXTentacion — that’s “ex, ex, ex, tentación” — gained a following as his breakneck trap brawler “Look at Me!” took clubs and concerts by siege. Elsewhere, Florida rapper Kodak Black logged hits in “Skrt” and “Tunnel Vision,” which laced sublime tracks with stark dispatches from his life in and out of jail on robbery and drug-possession charges. (His “No Flockin’” introduced the rhyme flow Bronx star Cardi B used for her smash hit “Bodak Yellow.”) This year Kodak awaits trial for a 2016 sexual-assault charge. A second similar incident from February has yet to reach the courts. Kodak’s latest, Project Baby 2, a bleak collection of musings on love and hopelessness, is No. 2 in the country this week. While X and Kodak shine on the album chart, Texas teen rapper Tay-K has crept halfway up the Hot 100 with “The Race.” It bluntly recounts the time the 17-year-old rapper and murder suspect clipped his ankle monitor and tried to outrun the cops: “Fuck a beat, I was trying to beat a case / But I ain’t beat the case, bitch, I did the race.”

A court case used to be an imposing obstacle for an artist’s growth, a setback artists fought for their lives to overcome, but in 2017, assault and battery cases don’t seem as damaging. In the same way that selling drugs sharpened Jay-Z and Snoop Dogg’s bona fides in the ’90s and getting shot nine times transformed 50 Cent from neighborhood rabble-rouser into a spokesperson for the streets in the aughts, proof of a young rapper’s reckless abandon now grows his legend and emboldens his authenticity. Would Tay-K’s song, or incarcerated New York rhymer Bobby Shmurda’s shoot-em-up anthem “Hot Nigga,” connect if every word didn’t feel lived? Would XXXTentacion’s mix of speaker-busting punk-rap and sad-sack campfire songs ring true if he seemed at all concerned for his own well-being?

Rap fans have a peculiar outlook on heroism because hip-hop culture exists as a monument to black inner-city craftiness in the face of crumbling infrastructure, tightening gang presence, and hyperactive policing. Injustice begat mistrust, which tripped off a thousand cat-and-mouse games between law enforcement and inner-city entrepreneurs, ranging from simple music and movie bootlegging and loose-cigarette and unlicensed-alcohol sales all the way up the chain to coke and crack manufacturing and distribution. Good and evil seemed porous and nebulous to a generation that grew up in the shadow of government neglect and police misconduct. Police could be seen harassing unarmed citizens; kingpins handed out turkeys at Thanksgiving.

Gangsta rap made folk heroes out of men and women who risked their safety to bend the rules and prosper as outlaws. The greats presented crime as a political act, a means of leveling a playing field that always operated on a severe tilt. They gave voice to the struggles of the disadvantaged and illuminated a way out for the daring. Harsh nationwide response — presidential rebukes, steamrolling CDs, obscenity trials — steeled fans of the music to criticism to a degree we’ve never quite recovered from. To love rap is to crusade for its honor, to suspend disbelief and enjoy it free of moralizing. This complex makes it tough to challenge the stuff even now; many a valuable talk on rap misogyny and homophobia has been derailed by passing the blame up the chain of command to America at large, instead of reckoning with the role of artists and fans in coddling social ills they, admittedly, didn’t invent. Comedian Eric Andre caught hell on Twitter this month for asking why people who hate racism entertain music that promotes sexism. It’s not a crazy question, but the timing never works. There’s always a bigger concern eating up attention.

While we hem and haw about how to even talk about rappers with open murder, battery, and sexual-assault cases, their success seems to render the conversation moot. Music fans’ mantra about compartmentalizing craft and crafter — “You gotta separate the art from the artist” — offers catchy, consequence-free support and promotion of artists who deserve more scrutiny. It has allowed decades of talented but abusive men to be celebrated as geniuses while the troublesome aspects of their lives languished in the back pages of history. It is not a noble thought process; it is apathy disguised as passing concern. The furthest the dialogue about XXXTentacion got was a handful of thinkers and long reads asking if he should be famous or not. While those gears turned, the powder keg personality set out on a volatile tour. At one stop, an opener got beat up in the crowd. Another saw X punch a fan in the face unprovoked. At a third, the rapper got knocked out cold and carried off in the middle of his own set. The whole tour was called off before I could check it out in NYC.

A consequence of centering a movement in unchecked male aggression is that it eventually becomes impossible to control, and to my eyes and ears, rap has been quietly spiraling toward a disaster for a while now. I distinctly remember the moment it became appropriate to mosh at a rap show, because it seemed to happen all at once. I caught a Diplomats show in Times Square in 2010 and watched one of a then-emergent A$AP Mob dive off the stage, accidentally spear the glasses off the guy standing next to me, and then offer to step outside if the kid was upset enough to fight. The same year I saw Odd Future turn the Studio at Webster Hall into pandemonium during their first show in the city. The next year, I caught a headline set by A$AP Rocky at CMJ’s Fader Fort that ended abruptly with a stage manager getting jumped and sent to the hospital for stitches.

Rap shows and rock shows have always run a little rowdy, but it wasn’t until recently that you could ever mistake the energy of one for the other. Rap shows got buck, but you watched where your hands and feet went so you didn’t get snuffed for stepping on kicks or breaching certain personal space boundaries. At a lot of rock shows, that kind of reckless jostling was the point. Nowadays, rappers pause shows to encourage fans to brace themselves for moshing. This isn’t to say that “rap is the new rock” because the two scenes have shared players for years. The Beastie Boys were a hardcore band before they landed on beats and rhymes, and the trio returned to those roots throughout their career. The early ’90s saw Chuck D pop up on a Sonic Youth song and KRS-One on an R.E.M. one. Living Colour, Faith No More, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers were heralds of a rap-rock revolution at the end of the ’80s that Rage Against the Machine, Limp Bizkit, and Korn would warp through the late ’90s and beyond.

The last bit should be a point of concern in examining the current rap landscape. Nu metal operated on a few core misunderstandings of rap in the same way a few key figures circling the rap mainstream are misguided in lionizing rock stars. The worst of it mistook rap for an art of baseless defiance and aggression, rather than a pointed shank forged out of disenfranchisement. In the space of a single year, Limp Bizkit devolved from scuzzy empowerment anthems to gibberish about sticking cookies up assholes. Even Rage, the most eloquent and pointedly political act on the scene by a country mile, saw its message grossly reduced to simple brutality in crowds screaming along to “Killing in the Name”: “FUCK YOU, I WON’T DO WHAT YOU TELL ME!” The whole scene folded in a frenzy of grabbing hands and flying fists, as Woodstock ’99 burned down, killing the ’90s as dead as Altamont did the ’60s.

As powerful and vibrant of a culture as hip-hop is, we’re always just one horrific event away from stifling nightlife reform. The repercussions for violence at a rap show trickle down to everyone, as New York showgoers can attest after a May 2016 shooting inside an Irving Plaza gig featuring Brooklyn rapper Troy Ave led to tightened security measures at shows and heavily armed guards at Governors Ball this summer. The more of a threat of violence that a rap show presents to a venue, the less of them they’re likely to book. It doesn’t matter how hot your single is if you’re seen as a security risk.

We owe it to the women who say they’ve been hurt by these artists to stop offering them space in interviews to trash their accusers before everyone gets their day in court. We owe it to the (increasingly) young fans of these guys — who place their safety in the hands of both artist and venue at every concert — to ensure that the performer onstage isn’t acting against the best interests of his audience (as the Houston rapper Travis Scott does when he goads fans to jump off venue balconies and ignore festival partitioning at his shows). The current climate of simply shoveling more money and clout at rappers with dangerous tendencies and hoping they’ll straighten themselves out is untenable. Labels need to do more training. Fans need to do more soul-searching. We need to ask more questions. Inaction is an action. History is watching.