Sharp Objects would be nothing without Wind Gap, Missouri. Location is a crucial part of HBO’s moody, visually arresting mini-series, so before director and executive producer Jean-Marc Vallée and cinematographers Yves Bélanger and Ronald Plante could work their magic in bringing Gillian Flynn’s novel to life, location manager Gregory Alpert had to work his to find the ideal setting.

The first thing Alpert did to get a handle on Wind Gap was travel to Missouri’s Bootheel region, the southernmost part of the state where Wind Gap was located in Flynn’s novel. Alpert’s mission was twofold: to find an isolated Victorian mansion to be the home of Adora (Patricia Clarkson), Amma (Eliza Scanlen), and Alan Crellin (Henry Czerny), and to scout communities that could serve as Wind Gap itself.

In the end, the 91-day shoot would span three different states: two days in St. Louis, 15 days in Georgia, 10 days in Northern California, and 66 days in 16 different communities across Southern California — from Santa Ana in Orange County to Lancaster, about 70 miles north of Los Angeles.

“Big Little Lies was all glamour and the women lived in an idyllic setting and a different world,” said Alpert, who also worked with Vallée that Emmy-winning series. “Here, we were stepping into this very dark, somber story. It was a whole different vibe because of the story we were telling. The darkness made this one more difficult.”

In an interview with Vulture, Alpert shared how he found the Crellin family mansion, what production did (or didn’t) build along the way, and why Vallée wanted Wind Gap to feel like a “ghost town.”

The Crellin Estate

Vallée had very specific marching orders for the mansion: “I want a house that if someone was screaming, you would never hear them,” Alpert recalled the director telling him.

At first, Alpert looked for houses in the Los Angeles area and found one in Altadena. “But we needed something more grand, so I started looking up and down the state for small towns that feel like Wind Gap.” Then he received an email from the Mendocino County Film Commission with a thumbnail photo of a house, taken with a long lens, that also appeared to have a small body of water in front of it.

The $6.2 million home in Redwood Valley, California (about 125 miles northeast of San Francisco), had just sold in the fall of 2016. Alpert spoke with the new owner, who purchased the home as a retirement property and gave the crew permission to see it, though no one would be allowed inside.

“Once I drove off the county road, the driveway itself is about a mile long,” Alpert said. “As I was driving up and the house exposed itself to me, I had one of those epiphany moments that, unfortunately, are few and far between. Oh my God! That’s the Crellin estate! I just fell in love with it. I did this quick 30-second video where I stood in front of it and did a 360-panorama and when I finally showed it to Jean-Marc, he went, ‘Boom! That’s it!’”

Alpert next had to convince the ranch manager, who had been in charge of the property for over 30 years, to allow additions and improvements to be made. At the time, the house was yellow and producers wanted to give it a more traditional Victorian color. Production tracked down the original painter, who had repainted it ten years earlier but had since retired, and hired him to change it to the blue-green color seen on the show. The main gate and fence to enter the property were added, as well as some landscaping.

“We were up against the clock and we didn’t want to bring out giant cranes,” Alpert said. “You had to put scaffolding precariously placed on some of the tiles. By tracking down the original painter, it gave comfort to the homeowner. We gave him two choices of traditional colors and he picked one with the understanding that we would leave the color.”

Meanwhile, production designer John Paino and his team built the entire interior of the house at Occidental Stages in Los Angeles, including a part of the patio to make transition shots seamless. “The house, although nice, didn’t have any of the grandeur that our set did,” Alpert said. “Any time you see Amy or Patricia walk in and out of a door, that was the extent of it. We were never inside the house.”

Downtown Wind Gap

When Alpert first started his search for Wind Gap, he had nine Georgia communities on his list. By the time Vallée was ready to tour for possible locations, Alpert had narrowed it to three finalists, all about an hour’s drive from Atlanta. The first stop that Alpert, Vallée, Paino, and executive producer Gregg Fienberg made on their road trip was Alpert’s first choice. But Vallée didn’t like it. “He thought it was too cutesy,” Alpert recalled, laughing. “Then we stopped and had lunch in Senoia, where they shoot The Walking Dead.”

On their way to see the pig farm that would become Preaker Farms, they drove through Barnesville, a town about 60 miles south of Atlanta. “What about this town?” Vallée asked. Alpert told him he had scouted it, but didn’t think it worked. (“John and I thought Barnesville was kind of cutesy.”) The director insisted on taking a quick drive through it anyway. After their visit to the pig farm, they drove to the last town on Alpert’s list, but Vallée wouldn’t even get out of the car. “No, forget that. Barnesville is the town,” he told them.

“John and I looked at each other and we said, ‘So be it. This is the town,’” Alpert recalled. “Jean-Marc really liked that town.”

Next, Alpert met with Barnesville officials, who were supportive and enthusiastic about the project. The last time any production had filmed there was the 1970s, and officials were willing to shut down the town for two weeks. Local businesses were compensated for being inconvenienced. “Jean-Marc wanted it to be ghost town,” Alpert said. “He didn’t want to see anyone, no cars, nothing. Throughout the series, there are a number of times no one is there. But everyone was so great — the local merchants, everybody. That’s why Jean-Marc is the genius he is.”

Production changed almost every storefront and all references to Barnesville became Wind Gap. One local store, owned by the same people who own the pig farm — an actual working farm near Barnesville — became the exterior of the police station. The exterior of the local bar was built in an abandoned building across the street from a Dairy Queen. The exterior of the Nash family home and the Mini-Mart station were also located in Barnesville.

“There were some issues, like a train that comes through town a couple of times a day and blocks the main drag,” Alpert said. “It just sits there for hours on end, so there are things we were warned about that came to fruition. Also, because there’s so much unscripted stuff that Jean-Marc does, like driving around town at night with Amy Adams in the car for hours on end, we’d have police officers and the fire department holding traffic and preventing people from getting into town so it could look like the ghost town.”

The alley window where Natalie is discovered borders the storefront that became the police station. In the book, Natalie is found in a gap between two buildings, but production struggled with where to put her in the TV show. “For the longest, we just didn’t know,” Alpert said. “At one point, we thought maybe we’d put her under a rail car that’s there. Jean-Marc wanted to feel that the killer was very brazen and put the body on display. We had just finished lunch and were walking down the alley to go to another location and Jean-Marc saw the window and said, ‘What about here?’”

The scene was filmed with actress Jessica Treska and a mannequin. “Even [Jessica’s] mother couldn’t tell who was the mannequin when we were shooting, so that was really troubling and freaky,” Alpert said. “When the older woman falls down to the ground and shrieks, you don’t really hear the woman scream because Jean-Marc wanted the reaction to be more from the inside of other people’s heads. That woman did that sickening sound all day long, take after take. It was just this horrific shrill. It made the hairs on my arms stand up.”

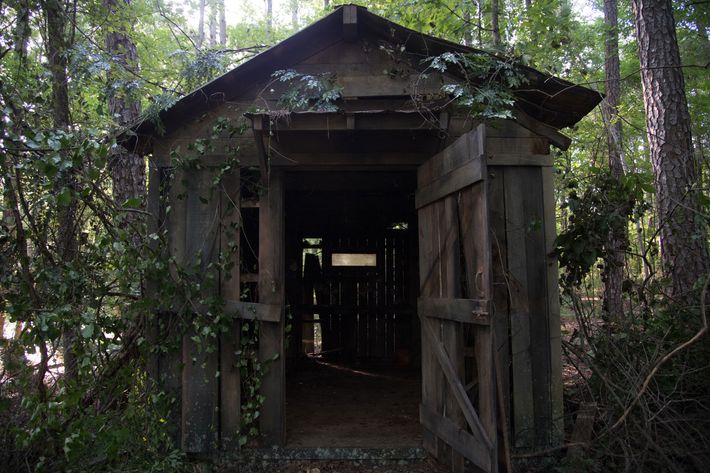

The Woods

Filming also took place on a private property outside Barnesville, including the hunting shed where the girls hung out, the wooded area where the girls spend time, the “End Zone” where Wing Gap teenagers throw parties, and the creek where Ann Nash’s body was found. “It’s a singular piece of property, but we made them feel like they were all in completely different areas,” Alpert said.

For the scene in the first episode, “Vanish,” where young Camille (played by Sophia Lillis) dips in a pond, production worked with the fire department to fill a dried-up duck pond on another property outside of Barnesville. “These are the little things that turn out to be difficult because Jean-Marc wanted her to be in a body of water encircled by trees,” Alpert said. “Typically, if you go to lake, or a pond, trees don’t go close to the shore. We took a hole that had been dug many years back as a duck pond, cleared it out, and filled it.”

Two local artists were commissioned to paint the town’s retro postcard-style murals, including the one with the waving woman that says, “Welcome to Wind Gap Missouri.” Production restored all references to Barnesville across the town when filming was completed, but the town council voted to leave the mural with the woman intact. “It just gave the place that ghost-town feeling, like the whole place had just been forgotten,” Alpert said.