Like a nightingale caught up in a footrace with a bioengineered cheetah ÔÇö having forgotten its wings and its voice in a befuddled attempt at high-tech speed ÔÇö contemporary theater can often feel like itÔÇÖs limping in the footsteps of its younger, flashier siblings, film and TV, struggling to keep up. Big producers point their money cannons at more and more eye-popping material, these days often plucked from the movies to begin with, and so we end up with Broadway-bound sparkling red windmills and giant animatronic gorillas: a glut of pseudo-cinematic spectacle ÔÇö often image-rich and imagination-poor ÔÇö that makes it especially poignant when a play like Rinne GroffÔÇÖs Fire in Dreamland comes along.

Now at the Public under the generally graceful direction of Marissa Wolf, Fire in Dreamland is a play about a film, but really itÔÇÖs a play about the untrammeled power of the imagination: to beguile and seduce, to construct worlds and provide purpose, to sustain, to deceive, and to revive. Though Groff is interested in intermingling forms ÔÇö her transitions are all jump cuts, signaled by the loud clack of a slate board wielded by one of the playÔÇÖs three actors ÔÇö her storyÔÇÖs central fascination with the act of its own telling seems to me to be what roots Fire in Dreamland as a piece of theater. ItÔÇÖs a play in which the greatest events are all narrated to us, passionately described rather than recreated. Though its subject matter might have made for a compellingly meta short film, and though its rhythm ÔÇö which often hops or meanders rather than drives ÔÇö at times makes it feel novella-like rather than grippingly dramatic, it still aspires, to paraphrase one of its characters, to whisper its story into our ears. That implies a unique fusion of physical presence and activated mindÔÇÖs eye that only a play requires, and that only a play can provide.

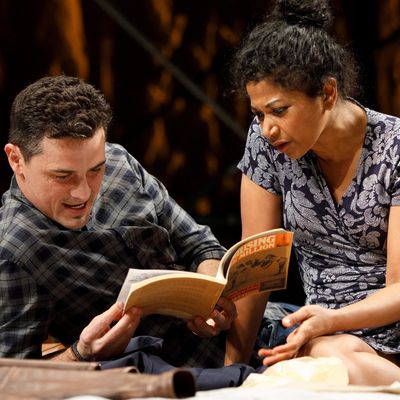

The players here are the disenchanted Kate (an effusive, hardworking Rebecca Naomi Jones), the charismatic Jaap (the square-jawed Enver Gjokaj, with a Dutch accent and an artisteÔÇÖs disdain for practicalities), and the nervously skeptical Lance (Kyle Beltran, armed with slate board, in excellent comic form). Jaap (itÔÇÖs pronounced ÔÇ£YahpÔÇØ) is trying to make a film about the catastrophic fire that destroyed Coney IslandÔÇÖs Dreamland amusement park in 1911. A few months after Superstorm Sandy, he meets Kate ÔÇö a smart, lost young woman with more degrees than direction ÔÇö down on the still-battered beach near the site of his movieÔÇÖs story. Kate hates her job administering corporate-sponsored ÔÇ£goodÔÇØ works (they just launched a ÔÇ£Privatized Playground Initiative,ÔÇØ she tells Jaap despondently), and sheÔÇÖs still mourning her social-worker father and struggling with his deathbed appeal that she do something with her life that has ÔÇ£meaningful impact on the world.ÔÇØ SheÔÇÖs desperate for something to believe in, and, man of vision that he is, Jaap is in the market for believers. ÔÇ£So right from the start,ÔÇØ to steal KateÔÇÖs opening remarks to us as she tries to describe the initial shots of JaapÔÇÖs film, ÔÇ£you pretty much know that everything is probably going to go very wrong.ÔÇØ

The film is JaapÔÇÖs, but the play is KateÔÇÖs, tracing her arc from disillusion to delusion and finally to newfound wakefulness and purpose. When we first meet her, Kate badly needs a dream, and Fire in Dreamland is partly about the dangers of throwing in with a master dreamer, the kind of soaring fantasist-slash-egoist who needs earthly disciples but will inevitably spurn earthly concerns. ÔÇ£I would rather have five minutes of unfinished, life-change amazing [film] than any bullshit, budgeting, piece of shit,ÔÇØ Jaap snaps at Kate during a gloves-off scene when the pair, long since committed both artistically and romantically, can no longer avoid facing how frayed the cloth of their dream has become. Kate, longing to bring to actual, tangible life the incredible scenario that Jaap has whispered in her ear ÔÇö and that weÔÇÖve had tantalizingly conjured for us in narrative form by Jones ÔÇö has thrown herself headlong into the thankless role of producing, and loving, a genius. But for all his energy and magnetism, not to mention his charmingly clueless American idioms, this ÔÇ£geniusÔÇØ is also a guy in search of a green card and a dropout of the New York City School of Film ÔÇö yes, the one with ÔÇ£the posters on the subway.ÔÇØ HeÔÇÖs got no phone (he borrows one), no money (he borrows that too), and no patience for anything that compromises the glory of his vision. He would have made a great preacher, but a directorÔÇÖs got to be half evangelist and half Clydesdale, and Jaap is a master of avoiding the work required to turn fantasy into reality.

The turns of Fire in Dreamland arenÔÇÖt shocking, but as per KateÔÇÖs ÔÇ£everything is probably going to go very wrongÔÇØ setup, they arenÔÇÖt necessarily meant to be. We can see JaapÔÇÖs charming duplicitousness ÔÇö which is monomaniacal but not malicious ÔÇö coming from a mile away, just like we can see whatÔÇÖs cooking when Kate spends too long in the bathroom and emerges nervous. Being slightly ahead of the story in instances like this feels understandable: After all, the play is suspended somewhere between KateÔÇÖs present and her past, and so some of it has the rosy tint of enchantment unfolding in real time, and some of it has the steely glare of 20/20 hindsight. But every so often the narrative thread slackens, and a point that feels evident is played for revelatory effect, as when Kate and Lance ÔÇö the mousy film student who, also beguiled by Jaap, comprises his entire crew ÔÇö have a eureka moment about connecting their project to the real ÔÇ£people on Coney Island right now [who are] making a comeback from something devastating in their lives.ÔÇØ Groff and Jones try to play this scene as a major turning point for Kate, whoÔÇÖs slowly emerging from JaapÔÇÖs shadow to rediscover her own creative autonomy. But thereÔÇÖs a disappointingly duh feeling to KateÔÇÖs realization, especially when she and Jaap have already drawn the obvious comparison between Superstorm Sandy and of the devastation of the 1911 fire in the playÔÇÖs opening scenes ÔÇö and when Fire in DreamlandÔÇÖs own marketing materials have made sure that we, its audience, have that parallel firmly planted in our minds before even entering the theater.

If Fire in Dreamland falters a bit in its tale  which remains compelling overall thanks to Groffs humor and sensitivity and the productions game trio of actors  it does so by never quite grabbing us fully by the throat. It has us firmly and kindly by the hand, and it leads us on a largely lovely journey, but theres pain and shock and betrayal along that path, at least for the characters, and in Wolfs rendering were kept largely insulated from these gut feelings. Jones, for example, is wonderful to watch as she takes us through one of the plays longest spells of narration, a spirited roller-coaster of a speech in which she describes the main thrust of Jaaps film: the proliferation of the fire and the horrific fate of Dreamlands trained animal population, especially Black Prince, a magnificent black lion whose tragic, spectacular death Jaap envisions as his masterpieces conclusion. In these moments of telling, of whispering into our ears and making us see, Jones and Wolf do their best work, but in rawer moments, that work can feel stiffer, less vividly alive. At the plays climax, after Jaap throws a cruelly calculated insult at the diligent, passionate Kate, she literally roars in response (Its the same roar as  the lion in the Fire in Dreamland film, Groff notes in the stage directions). A moment like this is a gift for an actor, but Wolf and Jones play it safe. Jones sounds like an actor who knows how to use her diaphragm to preserve her voice, not like a woman whose life is coming apart at the seams. It should be a dangerous moment of both despair and defiance, yet not enough is risked, and nothing breaks.

Still, Fire in Dreamland is an emotionally generous play thatÔÇÖs refreshing in its deep belief in the power of one of the oldest and purest forms of theater. Susan HilfertyÔÇÖs set, which fills the Anspacher theater with a minimal playing space of boardwalk-like wood and construction scaffolding, is simple enough, though I can imagine future productions of GroffÔÇÖs play in which the stage is even emptier, even more of a canvas for the imagination. ÔÇ£Think,ÔÇØ Groff and her characters are telling us, ÔÇ£when we talk of horses ÔÇö or lions, or mermaids ÔÇö that you see them.ÔÇØ We can, and we do.