Devonté Hynes is a real life Renaissance man. He sings, writes, produces, directs, and plays at least half a dozen instruments. He’s an avid reader whose music brims with references to historical figures and allusions to modern art. There’s a palpable social justice undercurrent bubbling beneath the surface. Over the last 15 years, Hynes’s restless creativity carried him from the raucous dance-punk and hardcore of the London trio Test Icicles to gorgeous, dejected folk and country in his early solo project Lightspeed Champion to the elegant, sometimes mournful soul of his current flagship Blood Orange. His knack for emotional candor in the latter project has led to great work writing and producing for other artists as well; the list of singers who have cut a song written by Hynes includes Solange, Carly Rae Jepsen, Sky Ferreira, and Haim. The guest list on his own albums gets more impressive with each release: 2013’s Cupid Deluxe wrangled Dave Longstreth of Dirty Projectors, the Queens rapper Despot, and former Chairlift singer Caroline Polachek. 2016’s Freetown Sound found space for Debbie Harry, Nelly Furtado, and Carly Rae.

On a certain level, Blood Orange is the document of Dev Hynes’s journeys as an Englishman in New York. Each record employs vocals from local legends and samples of metropolitan street noise. Recurring lyrical obsessions are blackness under fire (“June 12th,” “Sandra’s Smile,” “Augustine”), feelings of inadequacy (“Better Than Me,” “Always Let U Down”), and queerness (“Uncle ACE,” “Christopher and 6th”). Dev’s breathy falsetto and ’80s funk and dance music fixations are constants, but the performer’s sense of adventure keeps the Blood Orange project evolving. Freetown sampled Ta-Nehisi Coates and Paris Is Burning, turned a Charles Mingus song into mournful soul, and morphed rock/reggae singer Eddy Grant’s 1984 single “Come on Let Me Love You” into stately jazz. This week, Hynes unleashes Blood Orange album number four, the woozy, funky Negro Swan. The title references a lyric in the single “Charcoal Baby”: “No one wants to be the odd one out at times / No one wants to be the negro swan.” The album is full of songs about making the most out of a hard lot. Diddy contributes a hook about companionship in “Hope”; Janet Mock, the first trans woman of color to write and direct a television episode, provides narration, speaking about otherness in “Jewelry” and finding acceptance in “Family.”

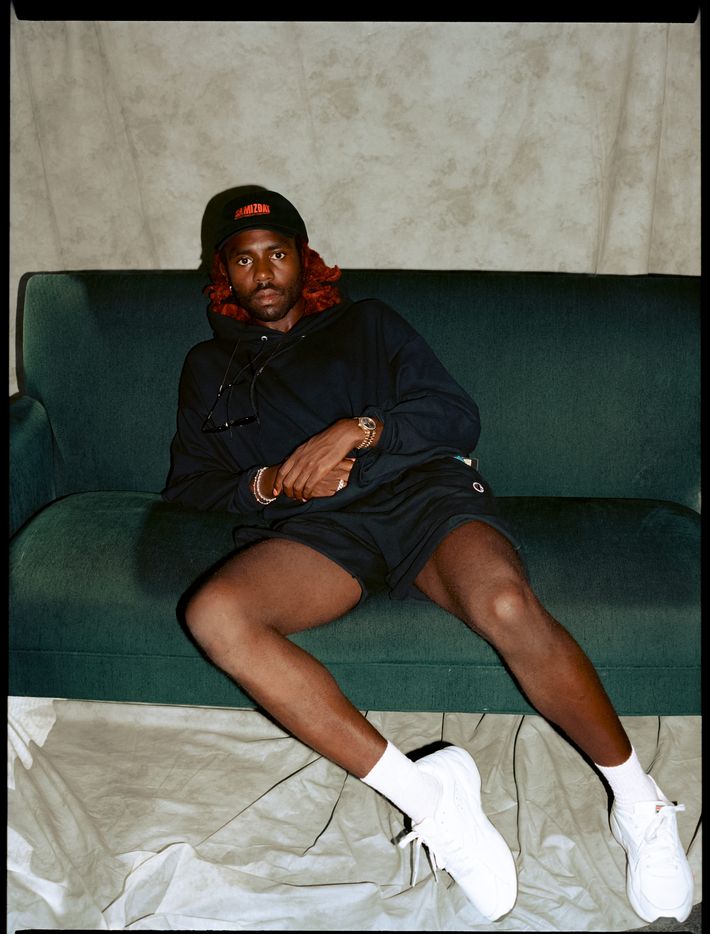

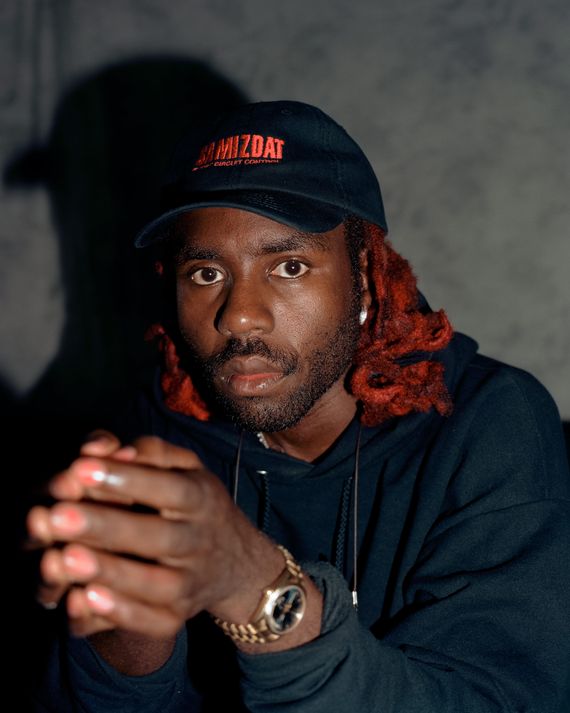

I met Dev Hynes at the Roxy in Tribeca this week to talk about his life, his career, and his new album. He’s full of ideas and melodies; he sometimes catches himself humming when it’s quiet. He looks relaxed in fuchsia-tipped dreads, a black Metropolitan Museum of Art tee, and a utility jacket I reckon this dreary, humid August is a touch too hot for. I soon realize it’s for carrying things when he produces a copy of The Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz from one of the pockets. “I’m someone who’s going to be studying until the very end,” he says of his vast range of interests. He worries about confusing people by moving in too many creative directions at once; there are two finished Blood Orange albums on ice right now, one created concurrently with Cupid Deluxe and another that came together alongside Negro Swan. We’re hearing Swan now because the artist feels it’s truer to his experience of the last few years. The new album was recorded in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. utilizing nothing but the available equipment on site at every studio, as a sort of self-imposed writing challenge. “I’m trying to get to the feeling,” he says of his mercurial recording process. “I’m just doing whatever I can to get there.”

I’ve always been curious how you got from the indie rock spectrum of Lightspeed Champion to the R&B and soul of Blood Orange. The overlap between those two projects was very short. The first Blood Orange album happened a year after the last Lightspeed one, right?

Yeah. They ran at the same time.

How did that work? Were you feeling like your creativity was splitting off in different directions?

I’m usually working on like five things at the same time. As much as everyone understands that everyone’s brain is always doing multiple things, people can’t actually take that. I never push everything I’m doing at the same time.

It’s weird for people to conceptualize you as an artist doing five things at one time.

Yeah. I think no one can handle that. Look at Kanye. The public literally can’t handle it. They can’t understand someone can make beats and design shoes.

He’s also given them a lot of reasons to have that reaction.

He’s definitely given them some additional situations. Yeah, second Lightspeed, first Blood Orange, exact same time. Palo Alto, Solange record, Blood Orange, exact same time. These things have kind of always happened. I also think the biggest difference between them is aesthetics. There are songs on the third Blood Orange, and even this one, that could have been on the first Lightspeed and the second Lightspeed. “Charcoal Baby” feels like a song from the second Lightspeed album.

How do you decide which project a song is best for?

Usually a feeling. I also write in such a weird way. I kind of write everything at once. I don’t mean at once, in, like, a moment. I mean everything is kind of like a big picture, and it’s being filled in. It’s rarely like, “Here’s a song.” It’s like … I have tracks 1–16, and I’m slowly working on all of them to fill up a picture. So there’s different ones of that. There’s another Blood Orange album that isn’t leftover tracks.

A whole different concept?

A whole other album that exists, and I don’t know when I’m going to put it out, or if I will. That’s happened before. There’s an album I made, same time as Cupid Deluxe. I think I just ended up putting it on a cassette and giving it to people. It existed as a whole other album.

What was the speed? What was the energy of that one?

That album makes sense as a link between Cupid and Freetown. It’s very frantic. Short tracks that jolt around, a little dialogue, almost like a mixtape feel. I was working on that, but Cupid felt … I guess if you were to look at them, it tends to be that the one that lyrically resonates the most, or the one that I view myself putting more of complete package together for is the one that I put out.

So you find yourself in a certain space, and one specific record feels like the one you should be pushing?

Yeah. I wrote this as … There was a period where I considered putting two records out at the same time.

There’s not enough of that. People put out double albums and long single albums, but it’s never two at once, like Bright Eyes with I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning and Digital Ash in a Digital Urn dropping the same day.

Iconic. The thing is, I think a lot of people work like that but just feel like they’re not allowed to.

It’s easier to understand what the artist is doing one piece at a time.

Yeah. I ended up focusing more on Negro Swan. I ended up visually focusing on it more and piecing it together and working on videos and imagery. I ended up living in that world more. If you want to look at it, Negro Swan is the diary of a couple of years. This other record I made was me “making a record.” Does that make sense?

You’re doing a lot of storytelling on this one, but the other one is a more deliberate “I’m writing pleasant songs” kind of a thing?

Yeah. It’s me working on beats and piecing shit together. Negro Swan is essentially, like … you need water to survive, but you’re not thinking about drinking water every second. It’s like the water of a couple of years. This other record is me being like, “Oh, maybe I’ll have a mojito.”

You write a lot of songs that end up being recorded by other artists. Do you write with specific voices in mind?

No, not really. There’s been only a couple of times through the years when I’ve done that. One moment would be on the last album. There’s a song called “Better Than Me” with Carly Rae Jepsen, who I love. That’s maybe one of the only times I ever thought of someone’s voice for a track. Usually it’s just whoever’s around. Just being in situations, hanging out with people, and playing stuff. If anyone has an idea, I’m always willing to hear the idea. If it works, it works. If it becomes their song, then it’s their song. I don’t really have a protectiveness over stuff. I’m not precious with music. I just want it to be the most interesting to me to listen to.

Sometimes that means handing it off to another voice?

Yeah. It could be a bassist. If there was a bassist in the room, and they wanted to try something on a song of mine, I’m like, “Try it.” You know? Like, “Wait and see what can happen.” That’s really how it tends to go down. I don’t necessarily think I’m the best person to finish a song, just because I started it. It can even be finished by a stranger in 30 years’ time. I don’t think I’m the protector of the idea. There’s a song on the new album called “Runnin’,” which has Georgia Anne Muldrow singing on it. Lyrically it was dark, but then she heard it and did what she did over top of it. Now it’s one of the most hopeful songs on the album. I never saw it going that way, but she took it there.

She has a very powerful presence.

I could never have taken it anywhere even close to that. That’s why I’m always into just … whoever’s around, just trying things. Life’s short. I just want to try shit and see what can happen.

You start the new album with “Orlando,” which is, to my ears, a song about a schoolyard scrap.

[laughs] That’s a pleasant way to put it.

Was growing up around London a positive experience? Was there trouble?

I think it was a bit of both. It was complicated, as some childhoods could be. I was beaten up a lot. Put into hospital and shit. I guess it sucked, when I think about it. I kept to myself a lot. There were people I was friends with … I tend to be friends with people through activities, which maybe is quite the common childhood thing. Skateboarding, or playing in school orchestra or whatever. Playing soccer. In fact, the only reason I started skateboarding was so that I didn’t have to take the bus. On the bus, people would spit on me and shit. So I started skating.

Was it just typical kid cruelty, or was there another angle to it?

If you want to be analytical of it, because I was a black kid wearing makeup, and painting my nails, and relaxing my hair and shit. People were just like …

Couldn’t handle it.

Mad confused. I was only — except for this one time where I was jumped by Kosovan immigrants, I was mainly beaten up by black kids. They were the kids that bullied me.

You have this line in “Orlando”: “All that I know was taught to me young.” I feel like you’re talking about being sort of indoctrinated into the cult of maleness and masculinity and the ways that men are expected to carry themselves. Is that what you were talking about?

Kind of. I never really know where I’m going in the song. I’m kind of just like going along, like a journal entry. I’m just putting these thoughts down. Throwing them onto paper. That song in particular, because it was half ad libs and half … That song was all one take, and it was the first take I did. I always knew I was going to do the … [hums a melody] Everything else, I just made up on the spot. I was trying to do what Marvin Gaye would do. There were certain lines that were written down, but I would ad lib them also. I’m almost looking at being this kid who … I never saw the restraints of what was proposed as a black male in East London when I was younger.

Is that why you ran into trouble?

That was exactly it. I’m looking back at that, and thinking about it in “Orlando.” Not even trying to understand it, but just thinking about it.

We teach children these very specific expressions of gender and attraction from birth. A lot of people rarely challenge them. It feels like you are interested in deprogramming that a little.

I guess so. [Pauses] It’s all very self-serving. If anyone can take anything [from a song], I would say that it’s cool. Usually, especially with this record, I think whatever people think is correct. I actually tried to make it that way. Whatever you take from it is actually right. Even if two people have different views, I think they’re both correct. I’m more just dissecting … I’ll have situations in my life, and I’ll look at it, and I dissect it, from my past and from there try and rewire something for it to make sense to me.

Because you didn’t understand it at the time?

Yeah. That’s kind of what the last two records are. Freetown was doing that more from a family aspect, but this one is more in terms of … myself as a child.

I’ve heard you say that the album is an examination of blackness and queerness and sadness. Talk to me about that.

Well, that was because I was being forced to give a press release. [Laughs.]

Had you not really thought about it that deeply, the theme?

Not at all. My dream is to just make something and people will hear it. That’s my dream. My dream is … Here’s an album, and people press play.

There’s still a truth to it. You’ve got the Janet Mock narrations. She’s talking about otherness. She’s talking about feeling like she has to perform normalcy for people.

Right. There’s definitely a truth. I guess I just hate telling people what something is, because I don’t want to … I guess my thing is, I don’t want to exclude anyone. There’s just so many things that do that in life. I never want someone to feel like it’s not for them, or they don’t understand it. I want them to get whatever it is they can get from it. I’ve felt like I’ve done that my whole life. I’ve taken whatever I can from things. Even things that I am excluded from. I’ve been like, “Fuck it.” And just taken what I can from it.

A lot of people feel like there’s art they’re supposed to pay attention to, and there’s art that they’re not supposed to pay attention to.

Yeah.

I don’t really get the striations. I guess that makes me weird also.

Right. Yeah. I’ve never got that. I just take what I can. Probably just because as a black person, people are straight-up consistently taking from black people. Whether it’s land or a kick drum. It’s being taken. I think I’ve always just been like, “Fuck it, I’m just going to take what I can.”

This year it feels like we may be, as a planet, advancing a little and regressing at the same time. There’s all this beautiful black art happening all over the place, but there’s also people calling the cops on us just for existing.

Yeah.

Are you hopeful about the future?

No.

Tell me more.

I should say I’m not hopeful about the future, but I’m optimistic.

I’m not entirely certain that things are the worst they’re going to get yet, but our problems right now could also be short term.

I just think things are always going to be bad. That doesn’t mean that we have to live in hell. It’s hard to explain that properly.

You make your own comforts. You find spaces and people, things that you can connect with, and it carries you through.

Everyone’s doing what they can. I don’t think anyone should sit around thinking … things get better. I always felt weird about that, actually. You remember that “It Gets Better” campaign? I always felt so strange about that. I get what people were saying, especially because it was [about] gay teen suicides. I understood it.

There’s value in the message, but it’s a little rosy, also.

Yeah.

It’s a bleak thing to say, “It Gets Better.” “The world is terrible right now, but stick with it.”

Right. I’ve never felt fully comfortable in that. I was a queer kid thinking of suicide. I don’t know — if someone said to me, “It gets better” — if it would have done anything. “It sucks now.” I don’t have a place I’m getting to with this.

I understand the experience. 20 years ago, I was in a dark place. I was feeling lonely. I told myself, “I’m going to put one foot in front of the other, and I’m going to keep going.” But if someone was like, “Hey, just keep going, buddy,” I’d have wanted to walk into traffic.

Yeah, exactly.

I get the value of it. I think it’s an important message for people to hear, but I wonder if it is more comforting to the people saying it or to the people hearing it.

Right. I think there’s a way you can say that things can get better, but know that you’re always going to face some shit.

What does queerness mean to you? How does it play out in your life?

To me personally, the idea of zero conforming and not thinking there’s a way to be. For myself, that’s what it is. It’s like, there’s no set guideline in life, with anything. It’s just, I take everything in, and I do what is the most natural for myself, my heart, and my brain. That’s what it is for me.

We get a rep in America as having tunnel vision about our specific experiences of race and gender. How do those experiences change for you as you pass between different countries? Are there places where you feel you have to be more or less mindful of things?

I’ve always been aware of my place here. I think it’s particular. For example, I lived here a decade, originally from London. Also, I’m 32, so there was an age where I lived without internet. Also, I live in New York. So it’s not just “I live in America.” I actually live in Manhattan. I think all of these things are so particular, and it affects how I live in black America in such a specific way. It’s almost like an outsider living inside. Not growing up in black America, but coming to it through my 20s. Even then, I’m looking at it through such a particular lens. I’ve traveled around, and I always feel that, coming from Europe … There’s always similarities, but the black experience is different. In England, the black experience is very different. Blackness is not … as deeply rooted in England. It only goes back 50 or so years, in terms of the idea of cultures breeding and creating life, and Brixton, and even my parents moving to London. It only goes back so far. I’ve always felt that … On top of that, you’re not taught anything. You have to learn it yourself.

There’s not a curriculum in schools?

I’m sure now it’s changed, but growing up, I had to go to the library.

We had very concerned black teachers making sure that we knew the history. My grandmother would take me to Apollo and make me watch hour after hour of documentaries.

That’s great. I didn’t have that. Especially where I grew up, that definitely wasn’t around. I always felt, maybe a few years later, like that sense led to me being bullied by black people. I think now it’s a little different, but growing up, it didn’t necessarily feel like that much of a community, where I was from.

Is it because of numbers? There are statistically less black people per white person in England, right?

Yeah. Especially where I was from. BNP and UKIP … British National Party in the U.K. would have seats in my area. Would win seats in my area. It was that vibe. You walked down the street, and you saw a British flag, and you crossed the street. That is what I grew up around. It’s very different now, which is probably why I’m really into going back to London more now. Where I was in growing up, I never got that sense of community. I felt very rejected. It was something I had to really wrestle with in life, because it was very confusing. It wasn’t until I moved to New York that I felt this kinship and relationship, which then helped me. I had insight to understand that upbringing and past. I never really blamed the kids that would beat me up. I didn’t hold any disdain for them because I think it was just a result of systemic situations.

So, you recorded Negro Swan all over the world. Is jumping into different studios a matter of bringing different energy out of yourself?

Yeah. It was all just experimenting. I was so curious what could happen. Like, those moments when I booked studios and didn’t bring anything, because I wanted to see what would happen.

That creates a logistical challenge, to see what you could make with what’s available?

Yeah. The last song on the album, called “Smoke,” is because I booked a room, and all they had was an acoustic guitar. So I wrote a song on acoustic. I can make stuff any way or any how, and it’s interesting to just play with that and see what can happen. I just travel the world with my hard drive and MacBook and just record in different ways, but then mix it so you can see what can go down.

You have Diddy on the record. He contacted you out of the blue?

That’s how we first started talking, yeah. He hit me up after Freetown came out, which is pretty crazy. He called me.

Procures your number and just rings you up.

Yeah. I think Om’Mas Keith gave it to him, but it was wild.

“Hope” is a departure for him. Usually, when you call Diddy for background vocals, you want to hear him cussing and yelling, like the Bad Boy records, but you got this really tender vocal. How did that come about?

I was working on the song with Valerie Teicher and … It actually came about because I started doing a fake Puff vocal. I started in the hook doing, [effects a mild Diddy impression] “I feel hope when you come around, yeah …” So there’s a version of me doing that. That was a real Puff kind of vibe. Then I was like, “Damn, should I just hit this nigga up and see what’s good?” So I texted him, and he was like, “Yeah, I’m with it.” Twenty hours later, it was done. It was kind of insane. I still freak out that that even went down.

I received the record without the features listed, and I was like, “Is this fucking Puffy?”

That’s sick. I love that. That’s my dream. That’s how I actually want all records to come out.

There are people doing that. The Travis Scott record didn’t list any of the features.

This is the first time I’ve ever listed features in my life.

There’s a moment in the middle of the album where a Project Pat vocal plays, and then you go into a Clark Sisters cover, which is, to me, very wild. Growing up in the church, you understood that those kinds of music were supposed to stay very far apart. What was the thought behind that sequence?

Every sequence on every one of my records is insanely thought out. If you think anything’s a mistake, it’s been thought about 50 times, at least.

You took us from the strip club to the church.

I viewed it as Saturday night and Sunday morning. That’s exactly how I viewed it. That’s why [“Chewing Gum”] cuts out with such extremity, and you have the crazy sounds and then it’s like the calm in church. Even at the end of that, it’s like you’re having that relaxation, and the end of the song, because I feel that Clark Sisters moment is so far from what you think would be on a Blood Orange record. Then, toward the end, I try and pull you back in with the 808 and the synthesizer and my voice being pushed to the front. That was intentionally pulling you back into my world, and then landing in “Dagenham Dream.” It’s all been thought out so much. It’s crazy.

We’re starting to see more use of gospel music in hip-hop and R&B. I don’t know if that’s because it’s just really good texturally, to use for samples, or if people feel pushed to return to spirituality …

Yeah. I’m not sure. Musicality. I feel like there’s periods, where every few years people decide that they want musicality. It bounces between extremes of just sounds, and then some people actually want music.

I think we’re in an everything-all-at-once kind of a moment. Travis has the biggest record out right now, and it’s thick and really lush. Then someone else will come out with a record that’ll be straight trap.

Slime Language.

Slime Language, yes! Do you like “Audemar?”

“Audemar” is the fucking jam.

It’s almost complete nonsense, and it is the hottest shit out right now.

It’s so fucking hot. Oh my God. I also love, what’s that song about clout? “Gain Clout.” That shit is fire.

Young Thug … it feels like he’s a displaced blues musician born into a rapper’s body.

I don’t even know how he fucking does it. I literally don’t know how he does it. I listen to songs like “Gain Clout,” and I don’t know how he’s made that. I’ve no idea how he’s made it. And “Audemar,” I don’t know how he …

Why is he thinking of this stuff. Why is he saying it?

It’s so fucking good.

It feels like it’s happening as it’s being recorded and that’s …

That’s the blues. I mean, that’s actually what the blues … Yeah. You’re totally right. You know who else, I think is actually a genius in that world is Uzi.

He’s definitely one of the up-and-coming greats.

I always wonder if people see it.

It feels like there’s no other time that he could have happened. I grew up listening to nu metal and rap, and it was considered a little weird. Now, this kid can rock a Marilyn Manson chain and sing pop-punk vocals, and it’s huge. I’m happy it exists.

It’s so sick.

It feels like he comes from a completely different melodic tree than rap.

Exactly. It’s always so interesting, people like that, because it always feels like the people that are fans of the world he occupies, I don’t know if they are seeing it. But then also people that could see it, I don’t know if they are willing to see it. I always feel that way about Carti, too. I feel like Die Lit is some of the most out-there thinking shit.

So, a lot of Blood Orange vocals hit like a choir, where there’s different tones and different genders delivering lines in unison. What’s the method there?

There’s always a feeling I’m trying to get to, and usually that’s the way to get to the feeling. There’s musicality involved, but it’s mainly feeling bits, to the point that when it comes time to figure out how to play this shit live, and I get a bunch of musicians in the room, I have to sit and dedicate time and work out what to fucking do. Because I am not thinking when I’m doing it. My friend, this guy called Mikey. Mikey Hart. Crazy, crazy, crazy talented musician. I got him to music direct for the live shows I’m about to do, because I usually do it, and my brain is just so occupied with shit now. My thing is that I do everything myself, but only because it’s a means to an end. I direct my videos because it’s easier for me to direct them. If there’s a place I feel like I can’t go, like the “Charcoal Baby” video, which I got Akinola Davies to do, then I will always get someone to go there. Mikey has been listening to the album, trying to work stuff out. And it’s funny because for example on track one, he’s worked out the culture and stuff, but none of the songs are really in key. They’re all in between keys, because I pitch and change things so much.

There’s a lot of that sort of woozy in-between key stuff on that record. It gives me a late summer, sweltering heat kind of feeling.

Cool. It’s like I’m trying to get to the feeling. I’m just doing whatever I can to get there. If it’s changing pitches and warping tracks so that they’re not even in time signatures or in keys, I will go as far as I can to that place.

Did you have a lot of training as a musician? You said you played in band.

I played cello in orchestra. Cello was the first thing, and then piano. My first music that I played was classical. After that was metal. It probably went classical, metal, jazz, and then from there onwards into whatever worlds.

Did you have to unlearn a lot? I know a lot of people who, when they get that training, have to talk themselves out of it to make music that isn’t, like, mathematically precise.

I think I was lucky, because I never finished anything. I never finished training on stuff. I always gained enough knowledge to know what I’m doing, but not enough to ever stop a creative process. In the years, I’ve gone back and studied more. I’d do classes at Juilliard and shit, but it’s always just to fill in some blanks so that could go into a different place.

So, you make records on your own, then there’s a process of figuring out how to play them afterward. I’ve seen you play twice in the last few years. It sounds like the record, in a good way.

That’s cool. It probably sounds better than the record. It’s hard for me. Live music, I have to really dedicate myself to it, because it’s the farthest thing from my brain, so I have to really just think Okay, now it’s a live show. What the fuck is this? How am I going to do it? Because I actively make my records so that you almost don’t think about my face. Then I have to stand in front of a bunch of people. Something about that really bothers me.

Your production, your artwork, and your choice of covers make me feel like New York in the ’80s and early ’90s is a major point of fascination for you. I’m also fascinated with that era, but it’s a grisly fascination, because a lot of the greats didn’t make it out of 1990. Everyone died.

Yeah. Exactly. Have you read this? [pulls a copy of the David Wojnarowicz book from his jacket pocket]

I haven’t. I feel like your art is a kind of emotional anthropology. You’re sorting through the past. You’re trying to learn through the experience of music. Am I wrong?

That’s pretty much it. I’m someone that’s going to be studying until the end. I’m always studying. For no reason. I think that comes out in the records.

Your album art, at least in the Blood Orange project, centers people in moments of peace, looking and feeling comforted. I think that’s what you’re also doing with your music. You try and create a space of peace for those people.

Yeah. Yeah. I’m also trying to create it for myself, but everyone’s welcome. You know? It’s important to me. For it to feel like a place. Like, an actual physical place.

Talk to me about Negro Swan, the name and the artwork. It has a beautiful cover.

Thank you. I think the title … Everyone’s view of it is correct. You know? I think it’s as … I think anyone can understand it. I think. It makes sense and you can pull from it any angle or direction and it’s right. I think that’s the first time I’ve ever named something like that where it’s like you can understand it very directly. Titles have tended to be somewhat abstract before that.

That’s probably why you don’t like to spell out themes, because if someone gains an understanding and it helps change their world, it’s like, “Who am I to keep them from that?”

That’s my whole thing. I just think it’s like … Yeah. No barriers. You know? That’s a 2018 quote.

That openness can be tricky for people, though. Everyone is 100 percent certain now that their understanding of the world is the truth. We have a lot of certainty where there shouldn’t necessarily be any.

You’re not allowed to make mistakes in 2018.

Certainly not. Do you feel pressure on your end? People don’t know who to trust right now. They’ll trust you as far as you say all the right things.

I think about it … I just don’t really care about it.

Is this why you’re not on Twitter anymore?

Yeah. I came back briefly. Then I was like, Fuck that. What am I thinking? I’d have to be psycho to even try and step into that world again. Yeah. I just don’t care about it. I would say that I care too much about conversations to be on Twitter.

It’s a place where you can talk to people, but they’re not necessarily willing to hear you out.

There’s no conversations. Everyone’s shouting. It’s like shouting in ink. You know? That’s not for me. I like to have real actual conversations with people. I just can’t. It’s a shame, though. I would love to be on Twitter.

It has a lot of problems they have no intention of fixing.

It’s never going to be fixed.