On July 13, the Whitney Museum will unveil “David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night.” It is an astonishingly relevant, urgently important retrospective. Miss it, and you miss transcendental levels of incredulity, indignation, vulnerability, lamentation, fighting back — ultimately, what it means to be human in a time of encroaching political darkness.

Today, David Wojnarowicz is known mostly as a martyr to the culture wars of the 1980s, another artist diagnosed with AIDS who fought along with so many to get the government to act, for a long time in vain, and who then, like so many others, died of the disease, a terrible tear in the fabric of art that was savagely exacted on gay men of that generation. Wojnarowicz came out of the same deeply downtown bohemianism of the early 1980s that fueled Jean-Michel Basquiat’s equally short, culture-altering arc through the art world: small cadres of like-minded underground characters and self-defined artists, desperate to act on the culture but denied the usual access to artistic power structures for reasons financial, psychological, racial, sexual. Wojnarowicz rose amid a gritty East Village aesthetic of graffiti, Expressionistic gestures, roughly assembled surfaces, funky found objects, one-night shows at clubs, and midnight guerrilla actions on the finer art. But in a way, Wojnarowicz’s tremendous, almost Rimbaud-like reputation suits, since he was an even better, more lucid freedom fighter than he was an artist.

At the Whitney, it’s all here, starting with Wojnarowicz’s own beginnings — growing up poor and on welfare in New Jersey; being abused, abandoned, kidnapped, and hustling on the streets of New York by the time he was 9; using heroin, cruising the piers and sex clubs, pouring blood onto gallery hallways, putting cottontails and ears on thousands of cockroaches and letting them loose in PS1, painting on pig skulls and tree trunks. In early 1988, he was diagnosed with AIDS and went through a supernova-like explosion into greatness, with his late paintings, photographs, collages, performances, and spoken pieces where — in a timorous, Robert Mitchum voice — he read piercing texts about “this killing machine called america,” “self-righteous walking swastikas claiming [AIDS] is god’s punishment … [a country] asking for a program to tattoo people with AIDS… isolate [them] in camps.” He wrote about how now “every painting or photograph or film I make, I make with the sense that it may be the last thing I do.” He charged that there’s “a Christian occupation in this country,” and imagined his friends putting his body and others of those who died of AIDS into a car and driving it “a hundred miles an hour to Washington, D.C., [to] blast through the gates of the White House … dump[ing] their lifeless form on the front steps.” William Burroughs said Wojnarowicz had “the voice of the traveler, the outcast, the thief.” Wojnarowicz’s feel for the existential crisis of being haunted by death and an alien society recalls Edvard Munch’s, and his fervently sermonic retaliatory prose comes as close as any American has to the impassioned accusations of James Baldwin.

The Whitney show poignantly documents how as soon as he spoke up, Wojnarowicz was caught in a triple hurricane. First, as a queer man, he lived in a society that openly wanted to “murder” him and found his desires disgusting, passing laws against his freedoms and attacking him at every turn. When diagnosed, he also contracted a diseased, pigheaded government that purposely refused to face the crisis — perhaps hoping instead that all gay men might die of it? — led by a celebrity president who for years declined to even say the word AIDS aloud. Finally, the full force of the U.S. government and various self-appointed Committee of Public Safety types singled out his art as being offensive and reprehensible and tried to stop funding for anyone who publicly attempted to show him. America saw Wojnarowicz’s work as a threat; America was right. The dying artist was fighting back with howling fury.

By the age of 37, when Wojnarowicz’s rage ended with his death in 1992, he had created a body of work and social protest so vehemently clear that he had not only remapped the nethermost reaches of Dante’s hell as an artist — pulling back the curtains of his own dying, his struggles against those who hated him and his kind — but had also given a living testament against the kinds of malignant evil and malicious vacuity that blaze out at the world again today. Wojnarowicz is a lighthouse of moral vision, courage, confidence, and resistance against willed ignorance, bigoted politics and policies that promote hate, nativism, resentment, denial, self-entitlement, and fear of the other. Sound familiar?

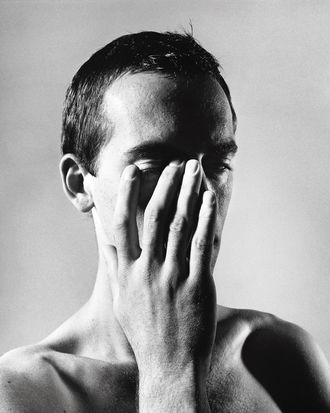

In 1989, the National Endowment for the Arts, under George H.W. Bush appointee John Frohnmayer, withdrew funding for Artists Space following the show “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” curated by Nan Goldin. The catalogue had an essay by Wojnarowicz that the government found offensive. The Reverend Donald Wildmon of the American Family Association published a pamphlet (i.e., a fund-raising brochure) with 14 homoerotic images lifted out of context from different Wojnarowicz artworks. One of the works cited was Untitled, from “Sex Series (For Marion Scemama),” 1989, seen on the previous page.

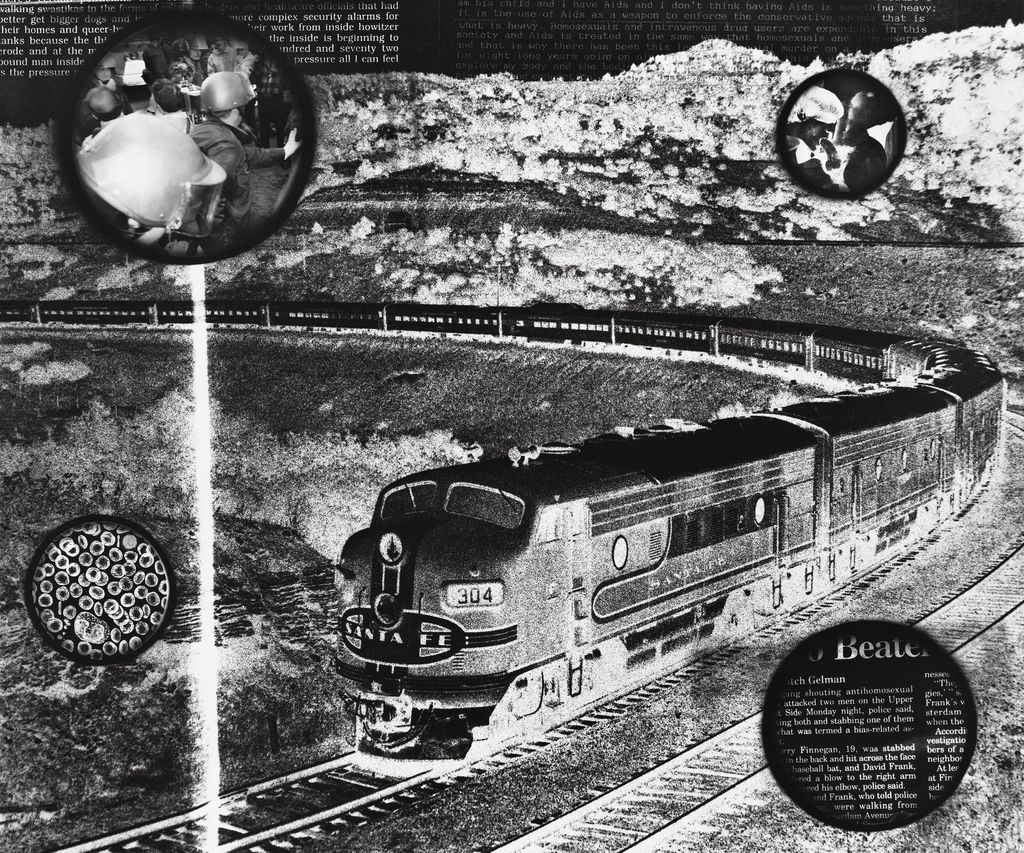

It’s at the Whitney. There’s none of the color, marks, or neo-Expressionist graffiti that mark much of his earlier work here. Everything has grown cold. A 16-by-20-inch photographic collage is reversed or polarized so that it radiates an X-ray fluorescence. What’s interesting is that those self-appointed Pharisees, whom Wojnarowicz later took on in a lawsuit for distorting his work, never mentioned this image’s background text — which is as hard to read as the offending fragmentary photograph. Focus on it, however, and what’s here is what should have terrified these sorts. Ultimately, Wojnarowicz won his court case, but his detractors were required to pay him only $1. It’s impossible to walk through the Whitney’s show in Trump’s America and not think over and over again to yourself, No justice; no peace.

Deconstructing the Art

The Text

In this text, he recalls watching TV and seeing a health-care official say that rather than give funding to people with AIDS, he wants to “spend it on a baby or innocent person with some defect or illness not of their own responsibility.” Such responses were common then; a Texas politician said, “If you want to stop AIDS, shoot the queers.” Wojnarowicz writes, “I reached in through the tv screen and ripped his face in half.”

The Cop

A photo of policemen harassing AIDS activists peacefully protesting the lack of AIDS-related drugs outside the Food and Drug Administration building.

The Sex

What got the zealots in a twist was this one small, hard-to-make-out, polarized image. If you look close, you see two men engaged in sexual activity. That was it. The pious hypocrites carefully combed his work for any such signs of immorality, blew them up, and accused his art of being mere pornography.

The Train

The large central image is of a modern Santa Fe locomotive pulling a long, curving train of passenger carriages through a Western-like landscape with mountains as background. Wojnarowicz saw this as representing the America in-between the coasts, the America that refused to see the deaths all over and that feared anything contaminating it from the outside. In this and many other ways, Wojnarowicz is a literal artist who wants you to know what his symbols and images represent. He wants you to be able to read his work the way people used to be able to decipher the sculptures on cathedral façades and know the Bible.

The Newspaper

A circular newspaper fragment about how a group of men beat and stabbed two men in New York City they thought were gay.

“David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night” is open July 13 to September 30 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

*This article appears in the July 9, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!