To describe the Metropolitan Opera’s season-opening production of Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila as gaudy, cheesy, and silly is a compliment, not a complaint. The director, Darko Tresnjak, embraces the work’s orientalist camp and labors mightily to save it from self-importance. The staging steers clear of biblical Gaza or any attempts at political timeliness and heads straight for the exotic sci-fi aesthetic of the 1950s and ’60s. Samson has a superpowerful mullet, Dalila a sunken den, lit in shades of mauve and teal.

Set designer Alexander Dodge veils the stage not with a curtain but with a mesh screen hanging from a rounded arch. Once that goes up, perforated screens and circular openings proliferate: high-tech allusions to traditional Arab latticework and Moorish arches, placing the action in a never-never Middle East. The opera is lopsided, as a friend pointed out, because being a Philistine is so much more fun, especially in Tresnjak’s production. They get the spiky crowns and blood-orange robes, orgies, some Arabian snake-charmer music, an idol the size of a Saddam Hussein statue, and a dance troupe with spray-on-gilt and the best buttocks in Gaza. The Jews get solemnity, resentment, and baggy white garb.

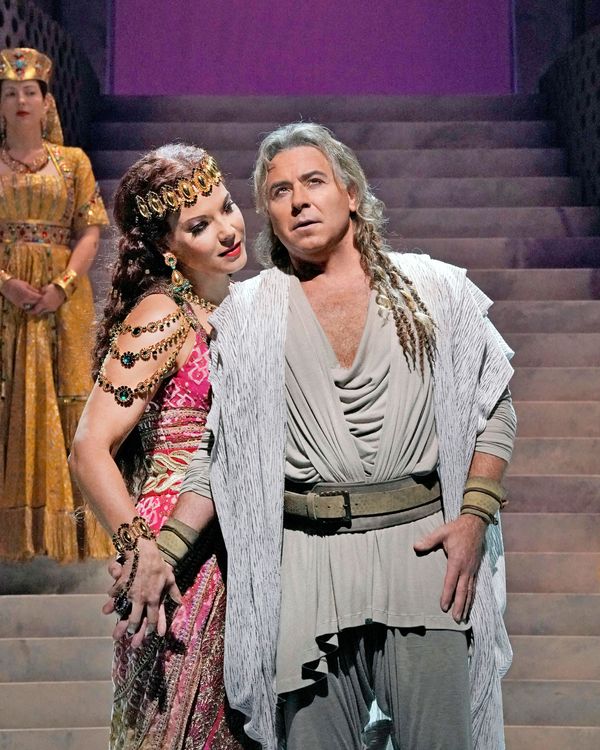

This story of clashing peoples demands big sets, big voices, a crowd of singers, a corps of dancers, and unlimited quantities of glitter. The Met supplied them all without apparently breaking a sweat. The company’s new music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, doesn’t report to the podium until a new La Traviata in December, so opening-night duties fell to Sir Mark Elder, who led a vigorous and supple performance. The orchestra and chorus shone with reliable brilliance. And yet all this machinery depends on the two stars, Roberto Alagna and Elīna Garanča, who carry the opera’s payload of romance.

Alagna’s Samson is a mopey kind of Avenger, davening through the first act, mooning over Delilah in the second, and moaning about his downfall in the third. He is at his best in Act Two, when his still-seductive voice intertwines with Garanča’s Dalila. He takes only occasional breaks for spasms of pious regret, which he signals with awkward twists of his torso or by resting his brow against a piece of scenery. Alagna was never an especially versatile singer, and here sad Samson, lovestruck Samson, and wrathful Samson all sound pretty much the same. But then if you’re looking for deep characterization, you’re at the wrong opera, anyway. Alagna gets through it by doing what he has been doing, often superbly, for 30 years: laying down his voice in a smooth, sweet line of lemon crème. On opening night, the squeeze bottle ran dry towards the end of the opera, and his last utterance sounded more like a cough than a righteous roar, but for most of the evening he was at ease making tones of unflappable tenderness.

Garanča tries harder to be a tough Dalila, the Philistine Mata Hari who beds, shears, and lords it over her musclebound dupe of a lover. But she puts her pagan scheming aside long enough to caress the central love scene with her seamless, high-gloss mezzo-soprano. Spectacle drops away, and the stage is cleared of extras, dancers, priests, and guards, leaving just a tenor and a mezzo who, for reasons unknown, feel that neither can live without the other. And for those ten minutes of vocal beauty, that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.