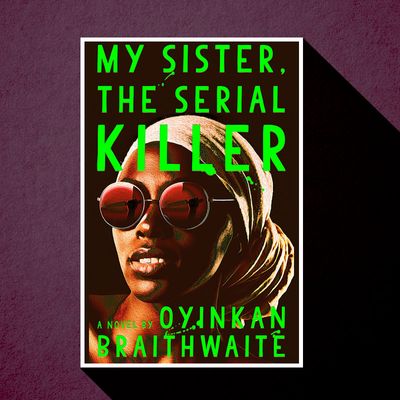

In Oyinkan Braithwaite’s noirish, critically acclaimed debut, My Sister, the Serial Killer, one sister kills men, and the other cleans up the blood and hauls away the bodies. The novel has been hailed as “an ideal book for the present moment” because of its portrayal of unlikable women joining forces to take down abusive men. But it’s a sly, slim read that resists easy political narratives. As the story moves swiftly toward its dark conclusion, Korede, the narrator, begins to suspect that the younger, more beautiful Ayoola, is killing just because she feels like it.

“Dark stuff comes naturally to me, but I didn’t want to bog people down in messages or morals,” Braithwaite explained in a recent call from Lagos. “I just wanted to tell a really good story, so I needed to keep it light. That’s where the comedy happened.” Midway through the story, Ayoola returns home from a trip to Dubai with one of her lovers, a new diamond comb tucked into her dreadlocks. “How was your trip?” Korede asks. “It was fine … except … he died.”

Here, Braithwaite walks us through how she conceptualized her serial killer.

My inspiration for Ayoola was the black widow spider. The first time I came across this idea of the black widow spider, I thought it was hilarious: the fact that the female will mate with the male, and if she happens to be hungry afterwards and the guy is still hanging around, she’ll eat him. I’ve been playing with the idea ever since. Years earlier, I wrote a poem about black widows. It was about two friends, one attractive, the other unattractive. The first would marry rich men, and then she would, at some point, poison them and gain all their wealth. Her best friend, the unattractive one, was the only one who knew this. And eventually, they are both after the same man. After that, I wrote a short comedy about two sisters who go on a series of dates with the same guy. They agree to may the best woman win, but they each keep sabotaging the other’s dates, and every time, it becomes more dangerous, until the guy actually dies in a fire. I also wrote a fantasy that had a tribe of black widows. I might go back to that one.

What really fascinated me about the black widow spider was that the males are not prey until the females are hungry, and if they’re not hungry, the males get away. They’re fine. That’s something I love about Ayoola — I don’t think her actions are always from a place of pain or revenge or self protection. Sometimes, she just does it because she can. There’s something freeing about that. She’s not this broken female who’s acting from a place of hurt. She has no sympathy for her victims, no remorse, no sense of consequence. She just does what she wants to do when she wants to do it. Out of every character in the novel, she’s the one having the best time.

I didn’t draw any inspiration from actual female serial killers, not real ones or ones from literature. Thinking back now, it’s interesting that I created a serial killer who is maybe a little bit sympathetic, because I used to have an issue with Dexter. I watched it, but part of the issue I had was, they’re making a likable serial killer and there has to be something wrong with that on a moral level. And then I went and did something similar. Ayoola does hideous things, but she’s also quite childlike. There’s an innocence to her. Because of that, it’s almost possible to still like her, despite the things she’s doing.

I’m not writing crime in the traditional sense. It wasn’t important to me to explore the murders, or to explore the victims, so much as it was to explore this dynamic between the two sisters. Both Ayoola and Korede are victims of their circumstance, and they’ve been feeding off each other’s quirks. Ayoola is childlike because Korede is always there to protect her, and Koreda feels she always has to protect her because Ayoola is childlike. They’re both playing their parts, and even though Korede hates the part she’s forced to play, she almost cannot do without it. I wanted to use the serial killing as a tool to explore how Ayoola uses her beauty to take these men by surprise. They don’t expect her to murder them, they don’t see it coming, and I wanted to explore why these men let their guards down. A lot of how we assess or judge people has to do with how a person looks and how a person carries themselves. If you carry yourself with a certain kind of confidence, people will buy what you’re selling, and this is something that Ayoola has realized.

I didn’t plot everything out when I started writing. I like to discover things as I go along. Because Ayoola is a serial killer, I knew she needed at least three victims. (I Googled that.) I didn’t want her to have too many, so it would still be somewhat believable that suspicion hadn’t been directed her way. For Ayoola’s weapon, I picked a knife. Fantastical as the story is, I tried to keep it a little bit grounded, and guns aren’t as easy for people to get in Nigeria. But knives, no one is really keeping an eye on them. I wanted the knife to be intricate and pretty. It’s not a kitchen knife. It’s something you’d pick up and look at and admire. I wanted to give it a history and its own personality to some extent.

I’m not sure if I think there’s something inherently feminist about a female serial killer, but I do believe strongly in a woman’s ability to do whatever it is she sets her mind to, and the characters in the book are strong women, maybe stronger even than the men. It’s important for women to know the power that they have, and I don’t mean necessarily the power based on the fact that they’re women, just that they have power, full stop. The same power that men have, and the same brains. A lot of the time we limit ourselves. Nobody really needs to do it for us. Korede limits herself because she believes certain things about her attractiveness and about her role as an older sibling, and she’s given herself certain limitations. Whereas Ayoola hasn’t given herself any, and Ayoola is the happier individual. There’s something to be said for that.

There’s this narrative that a woman will only commit a certain act if she’s been beaten into it, or if its a form of survival, or self defense, and I guess I wanted to see — what if it wasn’t like that? What if it had nothing to do with that? And there are still elements of that, but I liked the idea of looking at two women who have experienced the same sort of trauma, but they’ve responded to it in very different ways. Let’s not just assume that a woman isn’t capable of doing certain things, because perhaps she is, and perhaps we should watch out for her.