Mild spoilers for Roma below.

No one has an eye for curious ephemera quite like children watching TV. While glued to the screen, they’ll fixate on whatever seems most purely interesting to them, not caring about whether it’s regarded as worthy of their attention by more-discerning adults. What’s more, children will then hold on to their fixations well into adulthood and, if they come to wield some power in mass media, there’s always a chance they’ll revive these fetishized figures and items. Netflix has weaponized this nostalgia, conjuring up series and films that revive passing fancies of past generations, be they She-Ra or Stretch Armstrong. There’s an argument to be made that we should put Alfonso Cuarón’s Netflix-distributed film Roma in this category.

The film is an elegy for a bygone world, the Mexico of Cuarón’s own childhood; a kind of reboot of a whole country’s milieu. This vision is filled with things the auteur remembers from that primordial past, from the look of the streets to the presence of films that influenced him in his youth. But perhaps the most remarkable instance of unearthed cultural memory in the movie is the bizarre presence of a man familiar to Mexicans of a certain age, although it’s likely that they haven’t thought about him in a long time. He shone bright as the 1960s turned into the ’70s, then perished in a spectacular demise that still today is mired in mystery and controversy. I’m speaking about the man known as Professor Zovek.

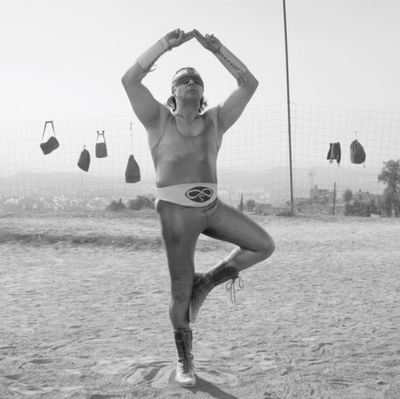

We see him twice in Roma, where he is played by professional wrestler Latin Lover. First, Zovek is visible on a television set in a restaurant, pulling a small car using only a strap attached to his teeth on famed variety show Siempre en Domingo (“Always on Sunday”). He’d be easy to miss if it weren’t for his unnerving second appearance: He arrives unannounced, clad in spandex, at a training camp for a right-wing paramilitary group and delivers the lads of the squadron a lesson about the power of the mind over the body.

There, he declares that he will perform a near-impossible feat. “Only the Lamas, martial-arts masters, and a few great athletes have been able to master it,” he says before having a volunteer blindfold him. He then raises his arms above his head and stands on one leg. The baffled crowd thinks this to be a joke until Zovek tells them to try closing their eyes and doing the same. None can keep their balance. It is, in a way, the film in microcosm: Acts that seem small and mundane from the outside can require tremendous effort and internal fortitude. After seeing the film, I had a sneaking suspicion that this extremely specific character might have some grounding in reality. Sure enough, I was right.

That said, it’s extremely hard to find any authoritative information about Zovek, who cultivated an air of mystery during his brief period of national stardom. Even if you do Spanish-language Google searches, you’ll only come across a single 1,400-word article about the man, a few shoddily produced YouTube tributes, and a clip from an episode of the Latin American edition of Drunk History (which, apparently, is a thing that exists). And that’s a cornucopia compared to the English offerings.

Nevertheless, a few key facts are indisputable. A fantastically gifted escape artist, he was referred to as “the Mexican Houdini,” though he also shared kinship with Bruce Lee insofar as he was physically trained to the point of almost being superhuman. He was only famous from roughly 1968 until his death in 1972 and left behind relatively little in the way of durable mass-media depictions. All we have are two highly obscure movies, Blue Demon y Zovek en la invasión de los muertos (“Blue Demon and Zovek in the Invasion of the Dead”) and El increíble Profesor Zovek (“The Incredible Professor Zovek”), the latter of which is unavailable in English. He eludes our grasp.

According to that single article, published by Mexican news outlet La Jornada in 1998, Zovek was born Francisco Xavier Chapa del Bosque into a well-to-do family in the northern city of Torreón in 1940. His early years were filled with pain and aspiration. He was a sickly boy, unable to walk due to polio, but he was obsessed with mythological stories of strength, particularly those of Hercules and Samson. He apparently had an uncle who tried experimental cures on the lad, leading to him one day walking in front of his awed family. The legend is that a relative exclaimed that it was a miracle and the boy responded, “What miracle? My own will made this happen.”

Young Francisco got into martial arts and wrestling and, by age 18, was apparently strong enough to perform public feats of strength — not yet under the Zovek name — such as pulling cars and trucks with ropes attached to his teeth. In 1966, for reasons I can’t seem to suss out, he began performing under the name Agent X-1, then in the late ’60s transitioned to calling himself Zovek (pronounced with the emphasis on the -ek). He would do stunts on television shows or at live events, drawing out crowds of increasing sizes. He once reportedly broke a world record by doing 8,350 sit-ups in under five hours on the variety program Domingos Espectaculares (“Spectacular Sundays”). By 1969, he was packing people into the Palacio de los Deportes stadium just so they could watch him burst from a straitjacket.

But Zovek’s true home was on one particular variety show: the aforementioned Siempre en Domingo. Zovek was a regular there, and his shtick is still imprinted on those who saw it as kids. “He was combining the mind and the body,” remembers cartoonist Felipe Galindo, better known by his pen name, Feggo. “He’d strap himself in chains and they’d hang him upside down. He would lift heavy stuff, like a car with people inside. He’d pull cars or heavy objects with” — you guessed it — “his teeth.” Zovek would surround himself with bikini-clad female assistants, all of them wearing BDSM hoods with the letters of his stage name on them. “Before he’d do his tricks, he’d say, ‘I need vibrations,’ and he’d lift the hoods of the women and kiss two or three of them,” Feggo says with a laugh. “In school, we used to make fun — if you saw a girl you liked, you’d say, ‘I need vibrations!’”

It helped that mass media was highly centralized in this period. There was only one major TV network, Televisa, by the time Zovek became a star, and the government leaned on it to show programming that would appeal to the masses without riling them up. Zovek was a perfect fit: entertaining but wholly unrevolutionary. “In the late ’60s or early ’70s, if you were on Televisa, you were everything in Mexico,” says Carlos Gutierrez, the executive director of an organization that promotes Latin American film called Cinema Tropical. “He was just part of the pantheon of Mexican popular culture.” As the decade turned, Zovek capitalized on his success by getting lead roles in the two aforementioned movies, both directed by René Cardona. They were incomprehensible schlock and classic examples of the so-called “Mexploitation” genre of zero-budget flicks about larger-than-life cultural figures — usually pro wrestlers — suplexing evil and the supernatural.

However, Zovek was tragically unable to enjoy those fruits of his labor. While filming the two movies, he died in public under circumstances that have never been conclusively explained. On March 10, 1972, Zovek was slated to be lowered from a helicopter down to the ground at a live gig in the central Mexican city of Cuautitlán. But as he descended his rope ladder, the pilot, Javier Merino Arroyo, pulled the helicopter upward and began turning. That threw Zovek off the rope and he slammed into the ground. He was taken to a hospital, where he died from fractures throughout his body. By the time of his death, there were rumors that Zovek was in cahoots with the government, training right-wing paramilitary groups, a notion that Cuarón presents as fact. As such, people whispered that the pilot had killed the performer as a political act of assassination. The pilot, for his part, always maintained that he thought Zovek was already off the rope when he levitated and turned.

Whatever the case, Zovek was gone and the first of the two films was renamed El increíble Profesor Zovek in his honor. His legacy continued somewhat in the form of his son, who performed escape acts under the name Zovek Chapa for a while. But for the most part, his brief period of stardom has faded away and he’s become a half-remembered curio. Cuarón’s decision to include Zovek in Roma and specifically to depict him as a reactionary operative is thus an act not only of specifically situating the film in a brief moment in time, but also of infusing entertainment with politics. “In a Mexican context, there’s a need for real heroes,” says associate professor of Mexican American and Latino/a Studies at the University of Texas, Austin Laura Gutierrez. “Zovek had these superhero qualities, but was also flesh and bone.” Cuarón has, among all of Roma’s other achievements, created something that’s desperately needed in our present age of superhero cinema: a reminder that we should never be entirely comfortable with our magical champions.