As one of the three actors who played the protagonist in Moonlight, Ashton Sanders didn’t get nearly as much acclaim or exposure as some of his talented co-stars, but I always felt like his was the most haunted, captivating, and demanding performance in Barry Jenkins’s film: He gave the teenage Chiron the vulnerability of a man awkwardly confronting his sexuality, and the submerged tension that eventually led to his blowup. And he did it with remarkable grace; you couldn’t keep your eyes off him.

That grace is center stage in Native Son, Rashid Johnson’s visually striking and stylized film of Richard Wright’s classic novel of class, race, and guilt, which just premiered at Sundance. As Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old bicycle messenger in Chicago who finds a job driving for a wealthy white businessman and his family, Sanders turns his character’s inner conflicts into action and gesture. He moves like a dancer — shoulders swaying, head nodding, hands trembling. This is a star in the making, but he seems determined to get there in a most unusual way.

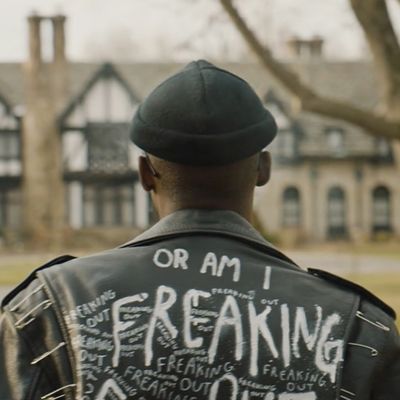

Sanders’s performance is not a naturalistic one by any stretch of the imagination. Nor is the film, for that matter. He may be iconoclastic in taste and dress — with his green hair, spiked collars, and studded jackets — but Bigger keeps being pulled back into what he calls “stereotypical Negro shit.” He likes classical music and metal, but his passengers seem to think he’ll want to put on hip-hop. His career options are limited — he can deal drugs, commit robberies, or become, effectively, a servant — and in his gestures we sense a man struggling to carve out a space for himself in the world. Every time he moves, he looks like he’s pushing, or carrying a weight; the very air around him seems heavy. Compare Bigger’s exertions to the zig-zagging freedom of Margaret Qualley’s Mary, the rebellious daughter of the wealthy family for whom he starts working. She seems wild, restless, capable of anything. The world is hers for the taking.

All this focus on movement certainly seems intentional. This is Johnson’s first feature — he’s a well-known conceptual artist — and he brings to the material a compositional and rhythmic savvy that feels confident and fresh, though it may frustrate those looking for a sturdier, more traditional adaptation. Written by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, Native Son meets Richard Wright’s original about halfway. The film is set in something resembling the present-day (though the time period is deliberately unclear) and it updates some of the novel’s broadest elements, but keeps many of its particulars intact. When Bigger is introduced to the ancient coal furnace that he must maintain as part of his duties — a key element in the book — it’s hard not to feel like you’ve either stepped back in time, or into a David Lynch movie.

Anyone who’s been exposed to Native Son at some point in the past — either in a high-school literature class or on their own — will remember the key, horrific event that sets much of its narrative in motion. And yet I hesitate to give it away here, not just because my audience at Sundance seemed unfamiliar with it, but also because by moving that grisly narrative development closer to the back half of their story, Parks and Johnson turn it into something of a reveal — not so much a denouement, but a climax nonetheless.

The result is a film that varies in tone, but purposefully so. Native Son seems suspended in time. By allowing for some anachronisms to live in their adaptation, Lori-Parks and Johnson seem to draw attention to the story’s universality — to the idea that the forces that ran the world in Wright’s time still run it to this day. But ultimately, this is Sanders’s show. His performance breathes new life into one of American literature’s most heartbreaking and controversial characters.