Once again, Vulture is speaking to the screenwriters behind the awards season’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult to crack. For this installment, First Reformed writer and director Paul Schrader unpacks an intimate scene between Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) and a young widow named Mary (Amanda Seyfried) who he’s been counseling. After her husband’s suicide, Mary seeks solace from her depression, a feeling Toller knows well. She suggests they try something she used to do with her husband: laying on top of one another, looking deeply into the other’s eyes. Schrader’s script goes beyond a staring game for lovers: Toller and Mary float up into the cosmos and across the wonders of the world. Schrader explained how he pulled off lifting his script from the trappings of reality into Toller’s spiritual crisis.

If a scene can’t be cracked, I work around it, or keep rethinking it in my head till I know it works. By the time I put pen to paper, I know the scene is going to work. I don’t think there is a “toughest scene I wrote.” That said, there was a scene in First Reformed that required a bit of imagination: the levitation scene.

I knew that at the end of the film, the story had to transcend the material world, and touch the world of the spirit. It’s a world that’s running alongside of us, that we feel we can almost reach over and touch. I knew that the main character had to get into that space. Before that could happen, we had to remind the viewer that this world exists, that there’s a spiritual reality right underneath us, or right next to us. I began to think, how can I convey that to the viewer? I was watching and looking at a lot of slow cinema in preproduction, so I thought to myself, What would Tarkovsky do? Well, Tarkovsky would have them levitate. Because that’s what he did.

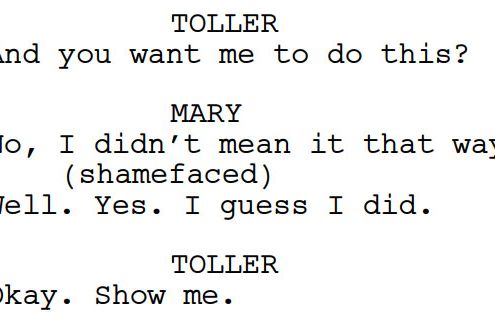

So now the question became: How could I get them to levitate in a way that wasn’t overtly romantic or sexual? I came up with this idea of Mary being in despair, and darkness, and coming over frightened, and talking about something that she and her husband used to do, a magical mystery tour. That became a way to put Mary and Toller in extreme proximity without having the trappings of a love story.

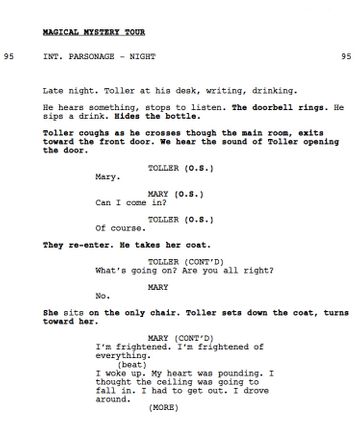

This particular script, like Taxi Driver, is written in chapters. There aren’t scene numbers, just chapters. This is called “Magical Mystery Tour.” That’s how I wrote the very first script of Taxi Driver: The chapters were called “Travis Gets a Job,” “Travis Meets Betsy,” like that. I went back to that format for this script.

The scene starts with Toller writing in his journal. When Mary knocks, he gets up and he answers the door. I had made it a rule of the film that the camera doesn’t move. So because we can’t pan, he just walks out of frame. Those kind of rules can free you because you do things you wouldn’t do otherwise. So now you have a tableau in this odd room, with no furniture in it, except a chair. It’s already kind of surreal. Then we wait, and then he walks back in. I put it in the script that he exits frame and comes back in, so I would not be tempted to waste time shooting a scene at the doorway, which I knew I didn’t want to use. One of the problems that happens sometimes is that you shoot scenes that you don’t want to use, and sooner or later, you start using them. You have to just commit yourself not to shoot it at all.

This scene gives Mary a chance to say the kind of things that Toller’s been saying, about how the curtain falls, how the blackness descends. Obviously, he knows what she’s talking about. There’s also a whole passive-aggressive romancing going on here: She came to see him because she was driving around and in despair, but also because she wanted to see him.

I trimmed this little bit of Mary’s dialogue. In the editing room, I felt that we were getting a little lost in information that wasn’t important. The real information that was important to the scene was the sense of hunger and emptiness in them. And all of a sudden, you’re talking about practical things, like antidepressants, and what’s the name of the child? I put that information in later, in a different place in the movie. A few scenes later Toller asks her, “Are we talking pink or blue?” That just felt like a nicer way of saying it.

Every young person, every young lover, has played this game, the staring game. Everyone plays with just the idea of it: How much physical contact is possible in a single moment? How much of your bodies can you line up, and actually be in contact with another person? There’s a little bit of a game in that, which keeps it from being purely lustful. It makes it all the more touching.

The first name for it was “80 Percent Solution,” because 80 percent of their bodies would be touching. Later I thought that “Magical Mystery Tour” was a better title, and I put that in. Then I realized, Why should I have two titles? “Magical Mystery Tour” is better. It’s something that people have a romantic association with, from the song.

Amanda is very good at those reticent agreements. Her face just sort of lights up. That’s a unique skill she has.

When I first started writing the script, I went back and watched all the films of this ilk that I had liked, or hadn’t seen yet. A lot of slow cinema: Tarkovsky, Bresson, Dreyer, and other filmmakers. It’s like being in a bookstore, or an art museum, you’re just sort of wandering around, trying to pick up influences, and you don’t quite know how the influences are going to hit you. I had all these movies in my head. I remembered the levitation scenes in Mirror, and Sacrifice, and just fell into that plot.

I held on that profile shot of the two of them for so long. You begin to see something in that shot that you wouldn’t see otherwise: the different silhouette line on a man’s face than on a woman’s face. The nose, the lips, the jaw, how they differ in sexual characteristics. Normally, you wouldn’t start thinking about that, but if you hold the shot long enough, people’s minds start realizing.

In that profile shot, her hair falls over her face. Because Amanda was actually pregnant, I wasn’t comfortable doing anything with him lying on top of her. When they actually started flying, that’s a stand-in. To cut between Amanda and the stand-in, I had to have the hairdresser ready to get her hair to fall into her face that way, or you wouldn’t have recognized that it was a different girl.

Once their breasts are conjoined, and once they inhabit this same space, then they rise up, in this particular moment. Whether they are physically rising or not is immaterial, but they are rising onscreen.

Rather than just end it there, like Tarkovsky would have, I tried to take it to the next level. They’re going through this Edenic world, this beautiful world, the world that God created. There’s all this beauty and glory, and they are in a mystical moment. As they travel, it’s just like in one of those films where an angel takes a person back to another time: They get to go see the beautiful world that is occurring all around them.

The despair has so corrupted Toller’s mind that he’s going to take this Edenic, blissful moment, and he’s going to transform it into the darkness that is inside of him. As the camera focuses more and more on Reverend Toller, the music becomes more and more discordant, and you realize that his mind is distorting this beautiful world.

It becomes like the three panels of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights. The first panel is Eden, the middle panel is the present day, and the last panel is the underworld. On this journey Mary and Toller take, they move from Eden to our world to the underworld. When it’s over, you realize that the course is set for this man. He has committed himself to this kind of darkness, and from that moment on, he starts moving in toward his suicidal calling.

Below, read the final scripted version of the scene:

Now see how the scene plays out in the finished film: