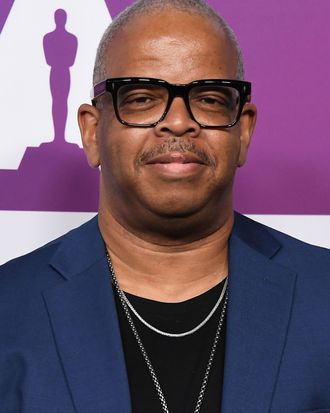

BlacKkKlansman not only earned Spike Lee his first Academy Award nomination for Best Director, but also the first nomination for his longtime collaborator Terence Blanchard. The jazz trumpeter, 56, has scored each one of Spike’s films since 1991’s Jungle Fever and he’s already earned his sixth Grammy for his song “Blut Und Boden (Blood and Soil),” which plays over the scene in which John David Washington’s Ron Stallworth is trying to prevent a Klan bombing. The Oscar nomination came as a surprise for the New Orleans–born Blanchard, not only because it’s his first in a distinguished career but also because he forgot which day the nominees were being announced. He only realized what had happened after he heard his daughter and wife screaming in joy from another room in his apartment.

As he wraps his head around the honor, which he calls a “culmination” of his nearly 30 years working with Lee, Blanchard caught up with Vulture to discuss meeting John David Washington and the real Ron Stallworth, hate in America, #OscarsSoWhite, and the weight of putting music to David Duke’s words and footage from the 2017 Charlottesville tragedy.

What do you remember about when Spike Lee first mentioned this project?

When he first told me what it was about, I said, “Man, you need to stop drinking. A black man infiltrates the Klan. Who came up with that story?” When I finally realized it was true, I said, ‘Okay, we gotta do this.’ [For the music,] he didn’t tell me what it needed. He just said, “R&B band,” and I told him, “Electric guitar.” I didn’t tell him why, but I wanted to use one because of Jimi Hendrix. I heard him play the national anthem at Woodstock when I was a kid. I thought it was very patriotic, actually,

Did John David’s look inspire that at all?

Oh, definitely. That very first scene, when he walks up, pats his Afro … Oh my God, the leather jackets and the bell-bottoms. That was my teenage years. It was as clear as if it was yesterday.

Did you have a sense of how important the movie was going to be?

I knew it was a powerful story but I didn’t know how much it would resonate. It made sense that people would respond this way because going to that film, they didn’t know what to expect. What caught them off guard is to think that all of that bigotry and hate that was back then. It’s a wake-up call when we get to that montage, to Heather Heyer’s picture. It’s startling for a lot of people to realize we haven’t gone as far away from this as we think.

The last song, “Photo Opps,” plays over the montage. What was it like composing that?

You want to write something that says, “We all know better,” you know what I mean? “This is not who we are as a people.” All religious backgrounds I’ve encountered speak about love and compassion, and the things we saw in that montage are the antithesis to that. I wanted to write something that was going to pull those heartstrings The song is actually taken from The Inside Man but readapted for that scene. It’s always been one of Spike’s favorites, so it just made sense.

What kind of responsibility do you feel to Heyer’s memory, having one of your songs play over that footage?

Well, you just be honest about how you feel. I was heartbroken to see that young woman lose her life over something so stupid. And to see it done in such a cowardly fashion. It’s one of those things where your heart just feels like it’s ripped open. I never met her. I didn’t know anything about her prior to that, but I knew she didn’t deserve that. Nobody deserves that. And that’s what you use as inspiration. Musically, I wanted us to heal from that, go through the grieving process to get to the other side.

What did it feel like having your music playing underneath hateful dialogue, like when David Duke is speaking or Trump says the “both sides” stuff about Charlottesville?

Well, it’s not something that you want to deal with but the reality of it is, it’s not something I’m not used to. I’m 56 years old and being from the South, I’ve been hearing it all my life. I didn’t want to glorify it but the music to me, in those scenes, is that intangible thing that speaks to the humanity within all of us.

Did you have to restrain yourself from making it sound too angry?

The performances by the actors were great enough. I didn’t feel like trying to push that envelope. One of the things about Spike is that when you watch what he does, he’s a humanitarian. That’s what he tries to deal with, so that’s how I try to approach the scores, constantly trying to allow people to deal with the fact that we know what’s right and what’s wrong.

It seems like a lot of composers or filmmakers could fall into that trap of making it too on-the-nose.

Yeah, there’s no need for that. It’s not our first rodeo with this. The approach for the music is to be exactly that: “Come on, we know what this is, we know where we should go.” It’s time for us to step up and be active. And yes, people are disheartened because 3.5 million votes wasn’t enough [in 2016]. A lot of people were complacent and now we’re feeling the effects of all of that. So what this film is speaking to is how we need to get off the sidelines.

Do you have a favorite moment from the film that coincides with the music that you wrote?

Not really, because the entire story is the most amazing thing for me. A rookie cop, African-American guy in Colorado Springs who just happened to open the paper and see an ad for the Ku Klux Klan. And he was such a rookie, man, he used his real name! [Laughs.] Which would be cute if it weren’t for the fact that he could’ve could’ve lost his life.

And the thing that’s really wild about it, when you meet Ron, he’s a gentle soul. This is what makes this guy special. He’s an ordinary guy who did an extraordinary thing and I’m very grateful for what he did for the country.

Did you get to talk to him about the true version of events?

I mean, when I’ve talked to him, I didn’t want to bother him. One of the things he said was, “Listen, man. I was young and dumb.” I don’t totally buy all of that. I mean, he may be young and inexperienced, but young and dumb? Not by any stretch. He knew what he was doing by making that phone call. By getting to the point where he wound up talking to David Duke, that must’ve been a miraculous feeling.

Obviously, you’ve worked with Denzel Washington a few times. What is it like getting to work on this with his son?

Oh, man. It made my back hurt.

Why’s that?

It makes me feel old! My knees start creaking and stuff. It’s like, “Wait a minute, man. I remember when you were born!” He’s a talented young actor. You gotta give him credit for being his own man.

I was watching him in Ballers and I go, “Man, there’s something weird about this kid.” Then I go, “Wait, what’s that sound coming from his voice? I know that sound.” Then I’m like, “Oh man, that’s John David? Get out!” I’d never met him but I remember Denzel used to talk about them all the time when he was a kid, when he was in school and playing football. Then when I saw him I’m like, “Oh my God. Look at this grown man.” It blew me away.

What has it been like to be an Oscar nominee so far?

You really don’t know what to expect. Everybody kept talking about this luncheon [for nominees] and I’m like, “What’s so great about this luncheon, man?” Then I get there and it was an awesome experience to be among your colleagues, see all these great folks who are very brilliant in what they do, and to see yourself amongst them. It’s humbling.

Did you get starstruck by anyone?

When you walk by Glenn Close, it’s kind of hard not to be like, “Goddamn! That’s Glenn Close!” And then in the picture, I’m standing next to Regina King, who I’ve respected for a long time. Then you have Mahershala Ali come over to the table and just say hi to me.

Did you talk to him about Green Book?

Yeah, I did, because [Kris Bowers] who I worked with for a hot second, he’s the one who scored it. Then we talked about basketball. He’s from Oakland, so he was throwing the Golden State stuff in Spike’s and my face.

Talking about Ali and King, there was that whole thing about #OscarsSoWhite and this year seems like a bit of a correction to that. What are your thoughts on that?

I know that they’ve been making an effort to do that. Hopefully this a sea-change moment. It’s interesting to be there standing next to Regina. I said, “Is this your first nomination?” She goes, “Yes,” and she asked me the same thing because we both thought each other had been nominated before and we haven’t.

And it’s the same thing for Spike.

Yeah. And I’m the second African-American to be nominated for a score since Herbie Hancock in 1986. Hopefully we’re moving in the right direction.