In April 2017, the leadership of the Society of ChildrenÔÇÖs Book Writers and Illustrators received a troubling email. Signed anonymously by seven female members, the note accused Jay Asher, a successful YA novelist whoÔÇÖd recently had his book adapted for a Netflix series, of using SCBWI conferences to lure members into sexual affairs. Adding that he had threatened them into silence about their relationships and made them feel unsafe at Society events, they pleaded with leaders to address the issue.

According to a source familiar with the correspondence, Lin Oliver, the executive director of SCBWI, discussed the email with Asher and his agent (whom the women had ccÔÇÖd). Asher admitted having had affairs with multiple SCBWI members, and the three of them agreed on a solution: Asher would no longer attend the conferences as a guest speaker. His literary agent wrote Oliver a few days later to praise her handling of a delicate situation. When the women wrote back, saying that they werenÔÇÖt satisfied by this solution, the agent wrote Oliver again to say that Asher had no plans to attend any of the groupÔÇÖs future events in any capacity.

No one told this story to the press ÔÇö not the women, whoÔÇÖd asked Oliver to keep their emails confidential, not Oliver, and not Asher. Only now, in the thick of a bitter lawsuit, is Vulture able to report what happened back then ÔÇö a quiet agreement followed by a long silence. In short, the affair was handled the way these sorts of problems almost always had been: discreetly, for fear of damaging anyoneÔÇÖs reputation. It seemed destined to remain private, spoken of in whispers if at all, as so many such incidents were before anyone had uttered ÔÇ£Me Too.ÔÇØ But this week, after a year of public fallout in the wake of a seismic cultural shift, Asher is suing Oliver and the SCBWI.┬áOne of his accusations ÔÇö that Oliver mischaracterized the circumstances surrounding his departure from the organization ÔÇö may have some merit. ItÔÇÖs unlikely for a variety of good reasons that heÔÇÖll win his suit, but the actual sequence of events does shine a light on how differently such allegations were handled even two years ago. AsherÔÇÖs complaint is far from the only one of its kind, and some worry that a flurry of defamation suits may risk forcing victims back into that era of silence.

The roots of AsherÔÇÖs lawsuit can be found in the comments section of an article last February about the childrenÔÇÖs publishing industry finally reckoning with the sexual harassers in its ranks. Asher wasnÔÇÖt named in the piece itself, but he came up repeatedly in the comments. ÔÇ£I, too, experienced predatory behavior from Jay Asher,ÔÇØ wrote one anonymous commenter. ÔÇ£He uses SCBWI to find young, new writers.┬áThe intimidation stops NOW. We will no longer whisper.ÔÇØ

The accusations went beyond Asher. Oliver herself was attacked┬áby commenters for her inaction ÔÇö and for giving one of her ÔÇ£darlingsÔÇØ special treatment. The organization had a longstanding bias towards certain men, the commenters alleged; its conferences were ÔÇ£breeding grounds for predators.ÔÇØ Oliver replied in the thread that she had, in fact, taken action: Asher and another member accused in the thread had already been ÔÇ£expelledÔÇØ from the organization. She was trying to protect herself and her group, but her reaction may have imperiled them. Last week, Asher accused her of defamation.

In a complaint filed in California, the author alleges that Oliver and the SCBWI maliciously destroyed his reputation and knowingly lied about him. He includes the substance of that first anonymous email, but writes, ÔÇ£these allegations were false.ÔÇØ His suit claims that the accusers were jealous of his success, that Oliver told him the emails read like ÔÇ£sour grapes,ÔÇØ and that one of the women later told Oliver the accusations were false. In a statement sent by Sitrick, the crisis management firm that once represented Harvey Weinstein, Asher claimed he was the one whoÔÇÖd been harassed ÔÇö that the author of the anonymous email had been bothering him for a decade. (He said something similar in an interview with Buzzfeed last year: heÔÇÖd had multiple affairs with women and then been harassed by them.)

But the heart of his lawsuit focuses on ┬áa statement Oliver gave to the Associated Press the day after she jumped into the comment thread. In an email to the AP, sheÔÇÖd written that Asher had violated the SCBWI code of conduct, that the claims against him had been investigated, and that, ÔÇ£as a result,ÔÇØ he was no longer a member of the organization.

AsherÔÇÖs suit calls that statement a defamatory lie, which ÔÇ£painted him as a criminalÔÇØ and damaged his career, leading to decreased book sales, cancelled speaking engagements, and expulsion from the second season of his Netflix show. (His agent dropped him, too.) The complaint also takes issue with a statement SCBWI released two days later, announcing newly crafted anti-harassment policies and procedures that will ÔÇ£ensure that SCBWI is a safe space for everyoneÔÇØ ÔÇö a statement he felt defamed him personally. All in all, he claimed OliverÔÇÖs actions exposed him to ÔÇ£hatred, contempt, ridicule, and obloquy at the height of the #MeToo movement.ÔÇØ

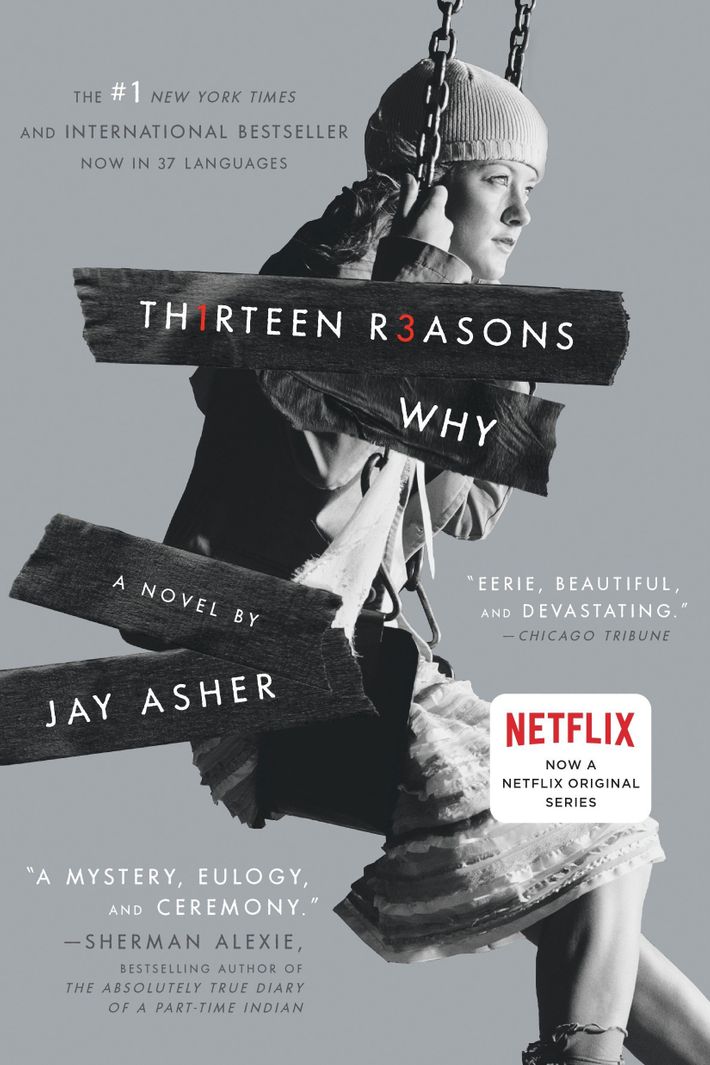

Reached for comment, OliverÔÇÖs lawyer declined to go into the details of the case, but he characterized the lawsuit as an attempt by Asher to repair his reputation ÔÇ£after it became public that his private actions were inconsistent with his public persona of being an advocate and ally of womenÔÇØ ÔÇö a reference, perhaps, to AsherÔÇÖs public support for #MeToo and to his novel, Thirteen Reasons Why, about a girl who is sexually assaulted and then commits suicide.

Asher is not the first man to sue for defamation in the wake of Harvey WeinsteinÔÇÖs reckoning. The era has been marked by an outpouring of womenÔÇÖs stories that had been buried for years, so it makes sense that the backlash, played out in suits like AsherÔÇÖs, would aim to force the stopper back in the bottle. In November 2017, the filmmaker Brett Ratner accused an employee who said heÔÇÖd raped her of libel. (He later dropped the case.) Last October, writer Stephen Elliott sued the creator of the Shitty Men In Media List for defamation. (His case is still pending.) The director of TimeÔÇÖs UpÔÇÖs Legal Defense Fund, Sharyn Tejani, told me that since #MeToo began, so many men have filed defamation suits that they are actively recruiting lawyers who can handle such cases. Tejani believes the defamation cases have had an unfortunate effect on the movement: ÔÇ£I think that people are afraid. They see it happening in the press, and theyÔÇÖre afraid that this might happen to them. It does chill people from speaking out.ÔÇØ

From the defendantÔÇÖs perspective, such suits can look like retroactive silencing mechanisms. ÔÇ£The clear message being sent is if you have the guts to speak out publicly about what happened to you in order to make sure that it doesnÔÇÖt happen to anyone else, then the ÔÇÿrewardÔÇÖ for your courage will be to be sued for defamation,ÔÇÖÔÇØ Robbie Kaplan, of Kaplan Hecker & Fink LLP, wrote to me in an email. Kaplan, who is representing Moira Donegan, the lead defendant in ElliottÔÇÖs suit, seemed confident, though, that these men would face an uphill battle. ÔÇ£The problem for Mr. Elliott and others like him is that there are strong protections in our country for free speech about matters of public concern, particularly in states like New York and California.ÔÇØ

AsherÔÇÖs case differs from ElliottÔÇÖs and others in one key respect: Instead of going after the women who accused him, heÔÇÖs suing the head of an organization he once belonged to, raising questions about how groups like these should handle accusations of serial harassment. Was Oliver serving her members best when she settled the matter discreetly back in 2017? Or did they have a right to know that heÔÇÖd left the organization, and why?

Rachel Arnow-Richman, a professor at the University of Denver who specializes in workplace law, said that the fear of defamation suits has historically enabled harassers: ÔÇ£What weÔÇÖve been seeing is stories of repeat harassers, where thereÔÇÖs reason to think that people knew about the behavior but it was swept under the rug.ÔÇØ Even when an employee is fired for harassment, itÔÇÖs not uncommon for the employer to keep this information a secret while the harasser lands a new job elsewhere. ÔÇ£Nobody wants a lawsuit and itÔÇÖs easier to stay quiet,ÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs an information-exchange problem that affects all of us.ÔÇØ

Nonetheless, defamation suits against employers or organizations are relatively rare for the simple reason that itÔÇÖs very difficult to win one in America. Several lawyers I spoke to were highly skeptical that AsherÔÇÖs suit would succeed.┬áÔÇ£I think thereÔÇÖs a very strong likelihood it could be dismissed right away,ÔÇØ said Bruce E. H. Johnson, who specializes in defamation law.

ItÔÇÖs particularly difficult to win such suits in California. The stateÔÇÖs so-called Anti-Slapp law places a very high burden of proof on the accuser, especially if the allegedly defamatory statements are about a matter of public concern. Among other things, Asher would have to prove that Oliver knowingly lied about his behavior toward the women, even though heÔÇÖs already admitted to the affairs, and their perceptions of harassment and intimidation canÔÇÖt be proven or disproven (never mind OliverÔÇÖs interpretation of their perceptions).

ÔÇ£If a woman or more than one woman complained about him, then the association is perfectly within its rights to remove him,ÔÇØ Johnson said. SCBWI also has the right to tell its members what happened, ÔÇ£and that right is only lost if the organization knowingly concocted false stories about him,ÔÇØ Johnson said. ┬áÔÇ£To all accounts, AsherÔÇÖs lawsuit looks foolish, and it looks retaliatory.ÔÇØ

Still, Asher could prevail if it turns out Oliver was lying when she told the AP that heÔÇÖd violated the code of conduct, been investigated, and left the organization as a result. The new evidence points to something different ÔÇö an informal private agreement. In a saga that revolves around whether a married man preyed on vulnerable women, the success of his lawsuit may ultimately hinge on more technical issues: What, precisely, was SCBWIÔÇÖs code of conduct at the time, and did he really violate it? Did Oliver really investigate the accusations? And did he leave on his own terms, or was he expelled?┬á(When the accusations against him came out, Asher said that he hadnÔÇÖt left the organization at all, which could technically have been true, though the source whoÔÇÖd seen the correspondence says he was effectively banned.)

If Oliver had handled the situation differently, itÔÇÖs possible that none of these questions would be in play at all. ÔÇ£There are probably a million ways that the organization could have written its statement that would make it much harder to make a defamation claim,ÔÇØ Arnow-Richman told me. ÔÇ£If the organization said factually: ÔÇÿWe received these complaints, we confirmed them with the victims, we donÔÇÖt know who said what and weÔÇÖre not in a position to figure out who did what. What we know is that the membership has expressed concerns and we think weÔÇÖd be better served by asking this person to leave and he has agreed.ÔÇÖ Then, they canÔÇÖt be liable for defamation.ÔÇØ

ItÔÇÖs possible that both Asher and Oliver may have given incomplete versions of how things played out between them. The details remain muddled, but itÔÇÖs clear that after receiving seven womenÔÇÖs complaints, Oliver and Asher and his agent sought to settle the situation quietly, appease the accusers, and move on. ThatÔÇÖs no longer tolerated in the current era. No single┬ádefamation suit is likely to change that fact in 2019 ÔÇö at least not for now.