Spoilers below for True Detective season three.

“May memory restore again and again

The smallest color of the smallest day:

Time is the school in which we learn

Time is the fire in which we burn.”

That passage from the Delmore Schwartz poem, “Calmly We Walk Through This April’s Day,” figured prominently in Sunday’s third season finale of True Detective, and for good reason. While the most recent iteration of True Detective may technically be about a case of missing and murdered children, it was far more interested in exploring how memory restores (or erases) important details, and alters one’s understanding of the truth.

The HBO anthology series is one of several recent crime dramas, both fictional and non, that consider how faulty recollections can affect our understanding of a narrative. True Detective, the first season of The Sinner, Sharp Objects, and docuseries like Lorena to Leaving Neverland each pose the same question: “What has been forgotten or denied here, and what does that tell us about human nature?”

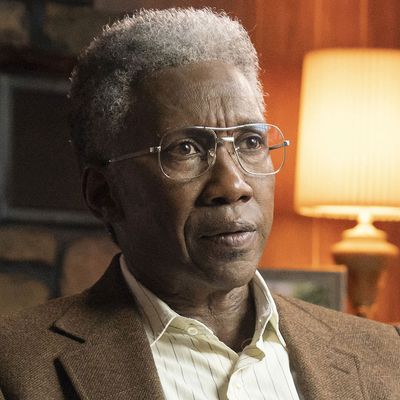

By the end of True Detective’s compelling third installment, it becomes clear that former Arkansas detectives Wayne Hays (Mahershala Ali) and Roland West (Stephen Dorff) have been looking at the unsolved 1980 death of Will Purcell and disappearance of Will’s sister, Julie Purcell, through a lens distorted by a string of misguided assumptions, as well as Wayne’s untrustworthy memory. The pursuit of the Purcell case unfolds over three timelines, including one set in 2015, when dementia has clouded Wayne’s brain and made his recollections about the 1980 investigation and the 1990 reinvestigation extra-foggy. Because Wayne acts as our primary window into this mystery, our sense of what happened to the Purcell kids is often as limited as his own.

Throughout the season, the directorial and editing choices convey the blurriness of Wayne’s memories, with moments from one timeline bleeding visually into another and visions appearing before him that may or may not be hallucinations. All of that calls into question the veracity of what Wayne thinks he knows. He’s a (mostly) honest man, but a terribly unreliable narrator. In the season finale, as the pieces of the Purcell puzzle finally fit together from our perspective, the visual timeline becomes even more frequently blurred: Just when it seems like we at last understand what happened to Will (whose death turns out to have been accidental), and Julie (who apparently died years after escaping captivity on the Hoyt estate), the episode suggests maybe we don’t.

During one of Wayne’s frequent hallucinatory conversations with his late wife, Amelia (Carmen Ejogo), she suggests that maybe Julie didn’t die at all and is instead living a happy life with her young daughter and husband, who once was the boy with an elementary-school crush on her. “What if,” Amelia asks, “there’s another story?” Ultimately True Detective never says whether Amelia’s theory is correct. When Wayne actually tracks down the woman who might be Julie, he has an episode and forgets why he’s driven to her house. The title of the finale, “Now Am Found,” which evokes the hymn “Amazing Grace,” could be a reference to Julie finally being found, or the notion that letting go of his quest for the truth, by choice or because of his illness, is the only way Wayne can find peace. Like so many modern crime stories, this one offers no solid resolution, but it does speak powerfully to the dance between denial, guilt, and forgetfulness that goes on when a person tries to sew up the loose ends of their past.

While it’s natural to connect this season of True Detective to previous ones, the show it most reminds me of is Sharp Objects. In that HBO limited series, Camille Preaker (Amy Adams) is not a detective, but she is a journalist investigating the murders of young girls in her Missouri hometown while also dealing with her own personal demons. Like Wayne’s issues, those demons are intertwined with the case she’s working. Camille doesn’t have dementia, but she is a raging alcoholic and an expert avoider of confronting family issues. The murky fluidity of her mental state is matched by the stream-of-conscious-style direction of Jean-Marc Vallée, which, as in True Detective, slides back and forth between Camille’s past and her present.

Sharp Objects is slightly less ambiguous than True Detective. By the time it’s over, we know how Camille’s sister Marian died years prior, and we know who’s responsible for the deaths of the girls in Wind Gap. It’s also clear that Camille knows all that, too. What we don’t know is how Camille will cope with what she’s learned. The mysteries may be resolved, but her work of adjusting, yet again, her grasp of her family’s dynamics — specifically those involving her mother, Adora (Patricia Clarkson) and her younger sister, Amma (Eliza Scanlen) — has only just begun. Her understanding of the story has changed again, one last time, as the credits roll.

The notion of memory informs other recent crime-dramas, including the first season of The Sinner, in which Jessica Biel plays a woman who kills a random stranger on a beach but can’t recall why she did it, and HBO’s The Night Of, which stars Riz Ahmed as an accused murderer who insists he’s innocent but, due to the use of drugs and alcohol, is unable to remember the moments that led to a woman winding up dead in his presence. While these two seasons of television tie up more neatly than Sharp Objects or the recent True Detective, they still present protagonists second-guessing their own realities, which highlights how suppressed memory and denial influences the way we interpret stories.

In a completely different way, Twin Peaks: The Return achieved something similar by activating the audience’s sense of nostalgia for the original series, then forcing them to consider the possibility of some other version of the Laura Palmer murder mystery. In the last two episodes in particular, co-creators David Lynch and Mark Frost trafficked in alternate history, resurrecting footage from the original Twin Peaks pilot but reframing it without the body of Laura (Sheryl Lee), wrapped in plastic, and having Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) take a woman who looks exactly like Laura to the Palmer family home, only to find other people living there. This is Lynch and Frost’s way of asking the same question that was posed by Amelia in the True Detective finale: “What if there’s another story?”

A number of docuseries and true-crime shows have posed this question, too. Even though True Detective can be viewed as an indictment of the type of true crime that re-litigates seemingly unsolved murders, it shares something in common philosophically with nonfiction-based television that revisits high-profile incidents with the perspective born out of hindsight. Both seasons of American Crime Story retraced significant cases from the 1990s — the O.J. Simpson trial and the murder of Gianni Versace — but did so in a way that compelled us to reexamine them with sharper eyes and more nuanced analysis of key figures involved.

Lorena, the Amazon docuseries about Lorena Bobbitt, John Wayne Bobbitt, and the former’s famous removal of the latter’s penis in response to years of abuse, does the same thing. Twenty-five years later, a situation that once sparked more crass jokes than conversations about domestic abuse now tells a different, much deeper story about society’s warped relationship with masculinity and its propensity to disregard women who seem too “angry.”

When it debuts on HBO this weekend, I’m certain that Leaving Neverland, the already controversial docuseries about two men who say they were sexually abused by Michael Jackson throughout their childhoods, will also force many people to reconsider their feelings about the King of Pop. While it’s not the first time that underage sex-abuse allegations have been raised about the singer, it is the first time that these particular victims and their families have spoken at such great length about how Jackson groomed them. The two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, talk at length about how their love for Jackson was so deep and their shame so profound that it took years for them to fully process that they had been abused. (The Jackson family has denounced the allegations, and the late singer’s estate has sued HBO for $100 million.) It’s the kind of documentary that not only colors anew whatever perspective you held about Michael Jackson’s alleged pedophilia, but also forces a personal assessment of our relationships with his music — relationships that, for many of us, were born when we were around the same age as the boys who say they became victims.

What both Lorena and Leaving Neverland do, essentially, is turn us into Wayne Hays. As we watch, we’re the ones looking back at past criminal cases and trying to figure out what really happened. We’re the ones realizing we overlooked or forgot important details. We’re the ones comprehending that when it comes to abuse, be it spousal or child, the truth is sometimes terribly complicated and depressingly straightforward all in one breath.

Though it’s largely a product of coincidence, it’s interesting that these memory-driven crime shows are gaining so much cultural traction at a time when discussion of politics and current events — including real-life criminal quagmires, like the one involving Jussie Smollett — tend to devolve into arguments in which people on opposite sides contend they know “the real truth.” All of the series I’ve mentioned here imply that to figure out what the real truth is, you have to keep your mind open, acknowledge false assumptions, and realize that memories don’t always reflect actual reality.

True Detective and other memory-driven fare aren’t necessarily trying to teach us a lesson. But if there is one to take away, it’s embedded in that Delmore Schwartz poem: Time can be a school in which we learn to cast the past in unbiased light and revisit it with the enlightened perspective that years can be generous enough to provide, if we’re willing to accept it.