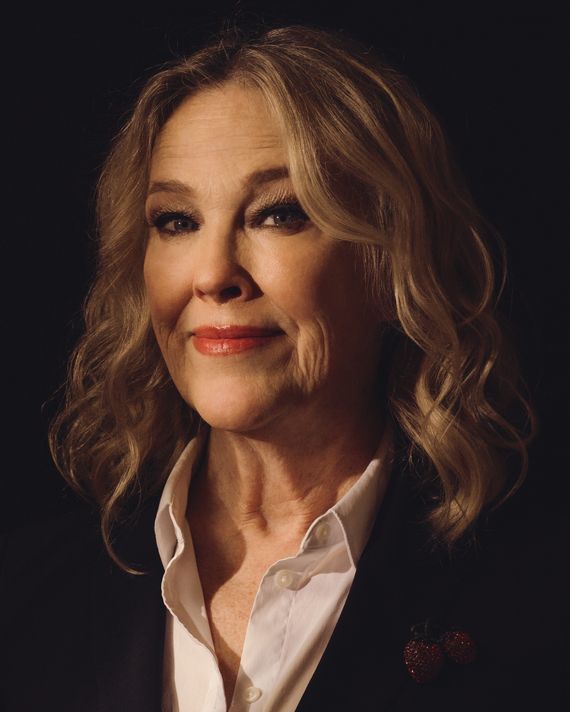

Despite an impressively long career, Catherine O’Hara maintains a Canadian humility in person — first off, complimenting my hair. She’s something of a secret hair expert: She honed her skills styling herself and her fellow cast members during the early years of Second City on the Toronto stage in the ’70s, and later on SCTV, to help generate a variety of characters. From there, her character work has been featured in multiple movies with Christopher Guest and Eugene Levy (Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show, A Mighty Wind, and For Your Consideration), Beetlejuice, Home Alone, and lately the television show Schitt’s Creek, in which she plays the worldly accented Moira Rose. “There are actresses who want to stick to one certain way, and there are actors like me who want to do a bunch of different characters,” she says. “Don’t fence me in! Don’t lock me down! I want to do different things! I don’t know who I am!”

Everything about Moira Rose on Schitt’s Creek is eccentric: the wigs, the clothes, the word choices, the diction. Is she based on anyone you knew personally?

The exterior always helps make me feel like someone else. For Moira, I get my hair done, I get my makeup, I get those clothes on. They make me stand differently and walk differently. I explain the voice as souvenirs from all my world travel. I’ve taken a bit of all the people I’ve met in the world and I’m sharing it with you. [Does Moira’s voice.] “Aren’t you lucky?” I was thinking of somebody I know who words things in a very particular way, and in an indecipherable accent. But broadly, you know, Madonna spoke English for a while. I think there was a part where Kathleen Turner was on a talk show and she sounded Brazilian. And you know what? Madonna is great at reinventing herself and going, “What do you mean? I’ve always been this way.”

You’ve said that you were reluctant to do the show at first. What made you change your mind?

Well, part of it’s laziness and not knowing how long the job is going to happen. But mainly, my training is in Second City, and I’m spoiled because I’ve been allowed to create my own characters and do my own writing and improvise and just create in such a free way. I was just used to playing a lot of different characters and having something new to do every day. That was my only real trepidation about doing a series. I’ve had friends who’ve been put in lockdown. Somebody talked them into committing to a series, and then treated them as if nothing they’d ever done had come from them, and now these people were going to tell them how to be.

So other people’s experiences were top-down, and not as collaborative?

Maybe [this was] only fear-based, and not reality-based for me. You just never know. I was trying to think of somebody I wanted to play in case the show went for any length of time, and it was great that Daniel and Eugene [Levy] made her an actress, because that gives her possibilities. Then I talked to Eugene about the way I want to speak. And then, “Could I wear different wigs?” And they said, “Yeah, in fact, we’ll give you a wall of wigs!” They made it so attractive on every level, and I’m so glad something guided me to do this, or tricked me.

You’ve said that some people like to build characters around a part of themselves, and others like to hide behind characters, and I was wondering if you felt pulled toward one pole more than the other?

I don’t think you can help but draw from yourself, especially if you’re doing improv. It’s all you have, that hard drive that’s still in there that you can draw from. At the same time you can start with, How would I look at this? How would I react to that? And then, you can consciously shift it. And once you start getting into the way a character seems to think, then it gets easier to improvise and be them. I don’t think any of us probably started out with any strong ideas of who we would become on this show. Even though you may have months to think about it, when you actually do this with other people, you have to be affected by each other. You’re not working alone there; you’re ever evolving with the help of each other.

What is the most personal character that you feel like you’ve played?

Oy. I don’t know. [Laughs.] I think that the one I resisted playing the most because it was just “a nice person” — and I’m not saying that’s me — but I was in an HBO movie called Temple Grandin.

With Claire Danes, right?

Yeah, I love her. She was so good. She kept apologizing to me off camera, that she wasn’t giving me anything because she couldn’t totally engage, because she’s playing an autistic person, Temple Grandin. She would apologize to me that she wasn’t totally connecting with me, I should say, on every level. I’d say, “Are you kidding? You’re Temple Grandin. What more would I want?” Working with her made it easy to just be there with her and want to take care of her.

But when I read it I was like, “Ah, it’s just a nice lady.” When you think of the great memorable characters, I don’t think that, generally speaking, they’re just regular nice people. Even someone in your life who you might think is just a nice person, they’re way more complex than not. Every human being is. But to read the thing on paper — and I often read things wrong or incorrectly the first time — I think it just doesn’t grab you right away. You have to sit with it and relax and forget about trying to show off. Not that I go into any job thinking that consciously, but I’m sure unconsciously you need to let go of wanting to show off and just be. That’s the trick in life, too. Just be.

Do you think there are character types that you did a lot of?

I was afraid I would lean on being a bitchy wife [with Moira] because I often did that. When in doubt, I played either insane or bitchy at Second City Theater. And I didn’t want to do that with Eugene, and I’m so happy either of us didn’t go the way of not loving each other. I think we’re a great loving couple in this.

I think there’s a bit of the sameness in a lot of the characters I do. I think there’s a lot of … insecure delusional. And I say this a lot, but I love playing people who have no real sense of the impression they’re making on anyone else. But the more I say it, the more I realize that’s all of us, and the internet, social networking, is a desperate attempt to try to control what others think of you. But look, we’re all trying to do that all the time. Anyone who reads your Twitter account as a follower — what the hell is that? I’ve never been consciously aware that I was hiding myself, but I also have never thought, I’m so interesting as myself. I’ll have thoughts where I think, Oh, that’s a good thought! That’s a good idea! I’ll share this! But generally speaking, who does think that way? Really?

Well, they’re all on social media.

But are they youthful maybe, and they haven’t actually found themselves? They’re going to look back on these words like bad hairdos from their youth. Like, Wow, I actually said it to the world? Whatever I did in youth, that’s pretty private! Whoever was there at the time saw how stupid I was. But wow, there’s no hiding what you do now! Anything you put out there is there forever.

A lot of people try to control the image they’re putting out there.

Good luck. Aren’t you going to have to show up in person at one point?

Some people try to avoid that, which is interesting.

My kids are 24 and 21. When I wanted them to get off their games, they’d go, “We can make really big money!” and they’d talk about [this] guy who plays games on the internet. And then I saw him on Colbert and there was no conversation. He actually showed clips from his work!

How much is social critique part of what you’re conveying?

Oh, that’s what Second City stage is. It’s all, “What did I see on the streetcar on the way to work today? Oh, I overheard a bit of conversation.” You hear them say something in a way you’d never heard anyone speak, and you go, “Oh, I’ve got to put that into something.” So you’re kind of gathering all these little bits of information. And it’s all laughing at ourselves. Not just others, but ourselves. Just behavior that human beings can’t help. We are ridiculous and great and lovely and sweet and innocent and scary.

How did you go about doing impressions of celebrities like Brooke Shields on SCTV?

Well, we all wrote for each other. Someone in that case would be writing “Farm Film Blow-Up” and would go, “Know who would be fun to have on?” — as if they were booking a guest — “Meryl Streep!” “Hmm, okay, I’ll try it!” “What about Brooke Shields?” “Oh my God, I’m in my 30s! What?” But we had amazing hair and makeup. And there was no internet then so it was, “Can you get me any tape?” My big fat VHS tape, I’d start recording things on TV, in the worst quality. But you’d record people on talk shows, and I’d seen Brooke Shields when she came out on Johnny Carson and did a tripping bit. Brooke Shields, God bless her, tried to do a bit. But because she’s a young, gorgeous girl who would stun men, nobody would give her the benefit of being funny. They all went, “Are you okay? Are you okay?” “No, I was doing a bit!” Nobody would believe her — except me! I believed her! No, seriously. I thought, Okay, they just won’t let a beautiful girl do that bit!

A lot of my impersonations were impersonations of Marty’s [Short] impersonations, because he did Katharine Hepburn and Liz Taylor. [Laughs.] You know when you see a great impersonator and you didn’t realize that the person they’re doing did that until you saw the impersonator do it? They let you inside the head of what they discover in somebody, to be able to impersonate them. Frank Caliendo from Mad TV did Bush in a way I’d never heard anyone do Bush, and Will Ferrell went a whole other way, but equally great.

When we were doing SCTV and someone would say, “What about this person? You want to play them in a scene? You want to do her?” If I didn’t like them, I wouldn’t play them. It takes too much of my time and energy.

Do you think that people have a right to be mad about impressions that are done of them?

It depends how they’re done. When you’re aware of the work that often goes into it, I think it’s a compliment that we might spend that much time thinking about and studying somebody, and trying to accurately portray them. But I think if you do a quick, grotesque version, then, yeah, they have a right to be PO’d or offended or just hurt. But depends how big they are. If they get it from all sides, then it’s part of the job.

You gotta see Anthony Atamanuik on Colbert; he talks about how he developed the impersonation of Trump, and it’s really good. It’s like a trailer from a master class on how to impersonate someone. He talks about his center of gravity, or lack of center of gravity, and he becomes him right before your eyes. He doesn’t even need that wig. No wig, no makeup, nothing. He becomes Trump before your eyes. It’s really, solidly good. He’s the best Trump ever.

SCTV was a fairly male-dominated space. Was it difficult getting your ideas heard during brainstorming or the writers’ process?

Yes. At the very beginning I’d whisper my ideas to Dave Thomas and he’d say them out loud, but he wouldn’t say, “Catherine said …” He’d say the idea out loud, and if it didn’t get a laugh I’d stay quiet. That’s what an insecure weasel I was. If it didn’t get a laugh I wouldn’t say anything, but if it got a laugh I’d go, “I said that! I told him to say that!” [Laughs.] It was like I had to go through the test kitchen of Dave Thomas!

That’s funny.

The sexism was still a holdover at that time. That generation of guys had been raised by an older generation, and depending on who raised them, they looked at women a certain way. But because they also did character work and not stand-up, I think they weren’t just working from their own ideas, so they were open-minded. I love those guys, and no one was ever cruel. It was just a case of numbers, and that was a product of the times. There would never be more than two women in a cast of Second City stage. Just this last year I asked Andrew [Alexander], “Tell me, have you ever had more women in a cast than men?” and he said, “All the time.” “Oh, thank God; that’s so great! What about anybody besides white people?” “Oh yeah, a lot.” “Anyone besides straight white people?” “Oh yeah, a lot!” So finally it’s opened up — like the world — but at that time it was two women.

You and Andrea Martin?

Yeah, but I worked with different women. When I first got in I understudied Gilda Radner, and then I understudied Rosemary Radcliffe, who’d been in the cast with her. Then I worked with Andrea. I worked with Robin Duke. At one point when Andrew Alexander gave the cast a holiday, they put an all-women show together, so it was Robin, Andrea, and Mary Charlotte Wilcox, and some other women. That was fun — all women. If one of the guys was writing a scene that was basically about men, they’d say, “And then the women come in!” as if we shared one hip. Can we be different women coming in at the same time? But again, it was the times. It was when’s women’s liberation was just happening. It’s changed.

Did you feel there was limit placed on the kinds of characters you could do creatively because of gender?

Yeah, of course. We’re drawing on life. We were parodying the world; we could only parody women who were allowed to do things in the world, women who were allowed to achieve certain things and have a public life. I think the reason comedy’s changed is because the world has changed. There are more women being allowed to reach for and achieve their potential now than then. It still hasn’t changed enough.

You weren’t credited as a writer in the beginning of SCTV. What happened?

That’s of the times. We weren’t paid as writers [in season one]. It made no sense. Andrew Alexander just said, “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. That’s the way things worked at the time.” He’s made up for it; we’re on equal ground now. And he was always creatively supportive of all of us. But yeah, money-wise, I don’t know how many workplaces still don’t pay women the same as men for the same job or better.

How did that change?

At the beginning I was so excited to be doing the TV show that it was like, “Wow, we get to create our own show?” and it was really thrilling. And I was never that money-conscious. At Second City Theater, I stupidly or naïvely thought, Wow, I get to do this? And I’m getting paid? So I never had a “Yes, I’ve earned this” vibe about me, or a consciousness. So when we did the TV show, same thing: “Wow! We’re getting to do a TV show!” I don’t think I was aware right away that we weren’t being paid. I think John Candy revealed it. John wasn’t paid either! John Candy and Andrea and I. John Candy made it known that Andrea and he and I were not being paid the same as the other guys, and John was a great fighter. He had great self-respect. So I’m sure I was encouraged by him. I can’t remember the details, but I loved him and he was a great ally in work and in all things. So I’m sure I was buoyed by his confidence. I’m sure I talked to [Alexander] and said, “What the hell?”

I realized all my training in negotiating was from SCTV because I realized, “Oh, when they say I’m not worth the same as someone else, it means they don’t want to pay me. It doesn’t mean that they don’t believe I’m not worth the same. They just want to try to get away with …” you know? And always ask for more than you’re willing to, so you come down to what you actually were happy to get. It’s not to take it personally is the big lesson.

For the Christopher Guest movies, is the script an outline?

Yeah, it’s a story outline. And actually the final result is exactly what that outline was. The whole thing is inspiration: Each actor is allowed to just fly. There’s no real discussion, unless you’re playing husband and wife. You might discuss it a bit if you have to. Like, in Best in Show, we did have to discuss dog training and dog showing. Eugene and I saw each other the first day of makeup. He had not told me he was going to look like that; I had not told him he was going to look like that! It’s so much funnier when you go, “Oh, that’s who I’m married to!” And whatever you might have thought of in a vague or specific way has to adjust.

Then you improvise it. Chris would just let us go, and on the second or third take, he says, “Okay, just go back to where you talk about where you met.” That doesn’t mean the dialogue has to be the same, he asks to go back because he knows he’s missing a beat that’s in the outline, or he wants to give it more focus. And then, “Do I go completely new now?” and “Oh, I came up with a joke, should I try to get it in?” “How fresh am I now in this take?” It’s really scary and fun to do.

Are you generally trying something new on the fly with each take?

Oh yeah, you have to be affected by everyone, and they’re all working on the fly. I learned that when you’re doing those kinds of movies, you learn you’re not alone, as you aren’t in life. You have others to build your characters, and you can help them build theirs by the way you treat them, by some incident from the past that you improvised and you shared with them. And you go, “Yeah, you’re right, I did.” The basic rules of improv are, “Yes, and,” and “No, but.” So you go, “Remember that time you tried to kiss me when we were in school?” You don’t say, “No I didn’t.” You go, “I don’t remember, but I do remember being naked with you later!” Or, “Yes, I remember, but I believe you asked me to!” You just always come back with something to offer, so we’re all building each other.

Was For Your Consideration also improvised?

Every one of them! They wrote that I would get a face-lift, that I’d be so sucked into the awards game, as you’re seeing right now. They talked about pulling it up [with tape] and I said, “No, I won’t do that,” because I knew even when I was in my 20s and 30s doing comedy, if I ever got pulled back, your face has to come back at the end of the day. And of course I’m not in my 30s when I was doing that. When was For Your Consideration?

2006.

Yeah, so I knew my older skin would have to come back at the end of the day. So I did just facial-muscle exercises, and then hold it as long as I could and do this weird eye thing I’ve seen happen to women who had inferior work done. [Laughs.] And the only really false thing was a set of teeth that we had made because I’ve seen on women that have a lot of work, what it does is, they lift their nose or bring their lip down so they have a much longer space than normal there, and my teeth were covered, so they made me longer teeth that would show. Big, white, straight teeth — which I don’t have. And then Kate Shorter, our makeup artist, gave me a great glossy, waxy, acid-washed face.

How did you practice that? Was it tiring?

You just lift. The more you do it, the more it stays! There are muscles behind your skin and face, and my mother did it her whole life. My mother never had a face-lift or any kind of cosmetic surgery. Her eyebrows were up here, God bless her, when she died at 81, with no wrinkles above. Her cheeks were up here! I’m not kidding. I wish I could show you pictures. When she was in her 20s, her eyebrows were down here. In her 80s, up here. And she would just hold her face like this. She had enough vanity that she’d look in the mirror, ask, “What’s the best way to look?” and she did it and it worked. She lifted her face naturally.

Was there ever a fork in the road where you imagine your career could have gone down a different route?

I’d have these meetings set up with studio heads and producers and directors, and I met them like they were interesting, or not very interesting, people. It was like a date, you know? I remember having lunch with Milos Forman. I worked with him on Heartburn. I was very intimidated on that set. I was with Jack Nicholson, Meryl Streep, Stockard Channing, Richard Maser, and Milos Forman. We were supposed to be three couples who were best friends. Okay — What was I doing there? That was all I thought at the time. I wanted to hurl the first day of rehearsal out of nervousness. Just sit there, just be quiet, just listen. And that’s Mike Nichols, God bless him, just picking out some little creature that he thought, Ooh, this’ll be fun to throw this into the mix. He did that with a lot of people, and a lot of smart people blossomed with that opportunity. He picked me to be in that group, and it was crazy.

Anyway, we finished the movie, and then a month or two after that Milos Forman asked to have lunch with me. I don’t even know what he had in mind, or if that could’ve led to another thing. I’m not even saying it could have been, but at the very least it was an opportunity to ask him about his life in Prague and where he’d lived. His childhood was amazing, with the little I’ve learned since. Why didn’t I take that opportunity to learn about his life? Instead I was like, Uh, what does it mean? Does he like me? Is this a date or is he thinking of hiring me and now I’m being judged? I was so ignorant, really, and insecure. So more than I could tell you about a movie I blew off, it would be opportunities like that. Because I claim to observe people and learn, and I didn’t in those moments because I was afraid I was being judged or assessed. And what a beautiful, interesting man that I could have learned something from, or even worked with again. I was just kind of ignorant. Oh, he told me stories and I swear to you, my response to some of his stories about his life were like, “Yeah right!” [Laughs.] That’s the saddest admission.

What was your experience doing a big, popular film like Home Alone? Did that affect how you were able to live your life or subsequent jobs?

Well, I’ll tell you right away, it was not a big film when I signed on. It was just a good script with some good people, John Hughes, Chris Columbus. Going in, I never had a sense of whether something’s going to be big or not, and I don’t think I’ve ever put too much thought into it because you can’t control that. It was not until I negotiated for the second movie was I aware that I was maybe part of a big project! [Laughs.] That was the most money I have ever been offered up front. That’s when I negotiated not to be there for all 12 weeks of the shoot. You could take more money, and be available for the whole shoot. Because we’re shooting interiors and exteriors in Chicago, and it was winter, so if you agree to be part of the whole shoot, then you’d be available for a cover shoot, which means if they have a scene scheduled to be outside and suddenly there’s horrible weather, or there’s no snow, they’ll shoot one of the interior scenes that was scheduled for another day. So on the first Home Alone, I was available to them for the whole shoot, and I was in Chicago the whole 12 weeks. If I went out for the day either shopping or sightseeing — and this was before cell phones — then I’d have to call in every once in a while to the first or second AD and be like, “Do you need me? I’m kind of a homebody, so for the second one, I didn’t want to have to be there for the whole shoot because I knew I wasn’t in every scene. So I took less money, which was still an insane amount of money, and they condensed my work. So that’s the only spot where I took advantage of the fact that it was a big movie. But that’s because it was a sequel, and the first film was so, so loved and still is. Wow.

A lot of mid-budget studio films have disappeared.

There’s no middle class in acting salaries in film anymore. In television, I guess there’s still money. I now get offered movies for $1,500 a week! They’re independent movies. There’s either big budget with Tom Cruise and Sandra Bullock and Jennifer Lawrence. You’re either the top one percent or you’re making it for the sake of art, with no money. So I guess it’s like the rest of the economy. [Laughs.] Someone like me, when I was just starting out in film, got really decent money. At least I was excited about it. And I was just starting out! The films I get offered now are little independent movies, and they’re way less money than I got when I was getting my first jobs in film.

It’s not just actors. My husband is a production designer and that world has changed as well. He used to go in, do an interview, and he had the job. He can still do that because people know his work, but even production designers who have done tons of beautiful work have to create these “look books” where they’re basically creating the look of the movie before their first interview. Sorry, I don’t mean to complain on his behalf either. It’s just recognizing that things have changed.

I know it was a blip, but I was curious to hear what you initially hoped to accomplish at SNL?

To do the same kind of work I’d done with SCTV. But we were so under the radar at SCTV, and I loved all the people at SNL. Like everyone, I thought it was the coolest show on TV. It was an opportunity to do it on a big stage and do it live. I thought, It’s going to be the greatest combination of Second City Theater and SCTV. But it was when SCTV was down. We were down many times between seasons. Andrew Alexander would fight his way into another deal, and he’d call us and say, “Okay! Now we’re on this network! Now we’re half-hour! Now we’re 45 minutes! Now we’re 90 minutes!” So it was on a downtime, and I got a call with the offer [for SNL]. It was in the summer before they were going on the air for that next season, and then Andrew called and said, “I made a deal with the same network, NBC, for 90-minute shows!” So I went to Dick Ebersol, the producer at the time, and said, “Sorry, I have to go back to my family!” It was that. There was BS in some book about me being scared. That’s not true. I don’t want to say this out loud, but it was boring what I saw, not scary. They spray-painted “Danger” on the wall. That didn’t scare me. It was a bad date. Not “bad bad,” just, “Okay, thank you.” Honestly, I do not look back on that with any pride. That was not a cool thing to do, to take the job, make them think you’re committed to being in that next season, and then run away or “go back to my family.” But I really did want to stay with my friends at SCTV.

So you wanted to stay with SCTV?

Yes. There was no job and then suddenly there was. Andrew made a deal. Nobody did anything awful. And even if they did, I could work with that. Who cares? But they didn’t.

Who’s doing improv and sketch comedy now that you like?

Well, I’ll always watch SNL for the great moments. There’s always something there. And I really miss Mad TV. There were so many good people on that. Groundlings, I’ll go there once in a while.

Who excites you on SNL?

Kate McKinnon’s great, obviously. She’s the star of the show right now. But I also really love Cecily Strong. She was kind of stuck in the news for a while there and you didn’t know what she could do, and I think she’s really good. On SCTV, I’d say Andrea was more Kate McKinnon and I’d be Cecily Strong. Maybe I relate to her more because she’s quieter about what she does. Not that Kate McKinnon’s loud; she’s obviously amazing and talented and funny.

After SCTV, you did less script writing, and I wondered if you ever wanted to write more of your own material?

At one point I sold a half-hour idea to HBO, but I didn’t even mean to pitch it. I just had a meeting with Carolyn Strauss, who was the head of HBO then, we had lunch, and she said, “Do you have any ideas for a show?” I told her an experience I’d had. It was something my husband and I went through. It was silly, but it was about being parents and the school function. And she said, “Yeah.” I said, “Yeah what?” She said, “Yeah, we’ll do it.” If I knew I was pitching I wouldn’t have made a deal! But because I just innocently told a story, I managed to pitch something!

What was the show called?

It was called Everyone Has One. It was basically about a marriage and what it goes through when you have children. But the pilot didn’t have a beginning, middle, and end. It didn’t wrap up. And I thought, That’s okay. That’s why I say it was ahead of my time! It didn’t sell, but I loved the opportunity.

You were doing “prestige TV” before anyone else was!

Anytime I get an opportunity to write and I’m given a deadline, I find out that I can write, and I gain confidence and I go, Why am I not doing it? This is stupid. But I don’t know, I get sucked into life — [Moira Rose voice] “and all that is has to offer!” Be with my kids, or my husband, or my friends. Or acting! But [Schitt’s Creek] has given me an opportunity to rewrite dialogue. I don’t have to, but I do and I want to, and Daniel [Levy] has made me feel welcome to do that. And I have a consulting producer credit, which just says, “Yeah, she’s doing something else.” But it doesn’t matter. I just do have the opportunity to write and it’s great. I would love to. Every year I say, No, this year I will actually write one of these ideas I have. I don’t know what’s stopping me. I guess I’m not that disciplined unless I have to. I need a deadline.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Willem Dafoe on the Art of Surrender

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’