It’s hard to explain the relationship between the superstars of the ’80s and their fans to people who weren’t alive or old enough to remember the decade. They were like demigods. They sang about love, peace, politics, and matters of planetary significance. Their art paused time and advanced culture. Their shows incited hysterics. It all seems religious in retrospect. Belief was the core of the bond, belief that these figures acted in the interest of bettering the world no matter the cost, belief that people who do good are good. Their methods and their presentation were questioned, but the idea that pop stars were out to save the world was quite often taken at face value. This was not wise. We didn’t know any better.

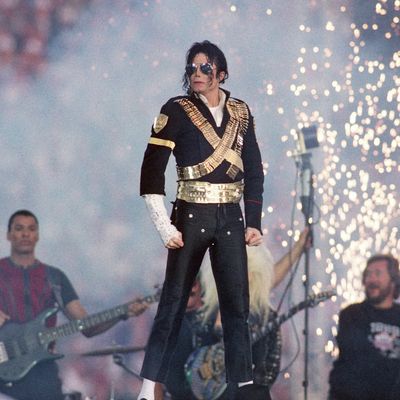

Watching the 1993 Super Bowl XXVII halftime show now is a clinic in the pure power of pop stardom and the mania of fandom. The guest, Michael Joseph Jackson, used decoys, hydraulics, and pyrotechnics to give the appearance of zipping from one end of the Rose Bowl stage to the next. After the smoke settled, the real Jackson sprung up out of the center of the stage dressed like a king in glittering military gear. For nearly two minutes, he stood stone still, sphinxlike and statuesque, while the audience shrieked in anticipation, each subtle micromovement sending the noise in the crowd even higher. It’s an unthinkable, unrepeatable act, using the nation’s biggest stage to erect a frozen monument to yourself. Jackson represented both power and magic, a ray beam of selfless good and unprecedented talent. But it’s a messianic story, perhaps a touch too good to be true. As the Jackson 5’s preternaturally soulful kid brother and lead singer, he was deprived of a childhood by an abusive workhorse father. He suffered, we were told, and then he came back to give us all the childhood he could never have.

British director Dan Reed’s HBO documentary Leaving Neverland suggests that something else was going on. The four-hour special centers on James Safechuck and choreographer to the stars Wade Robson, who found their way into Jackson’s orbit at the height of his fame. Both men detail graphic sexual encounters with the star over years of visits to his Neverland Ranch — alongside archival footage of Jackson hanging out with the children and their families and calling them by special pet names — and the lengthy fallout their families have experienced as a result of the singer’s involvement in their lives. It’s a knotty situation. Jackson was never formally found guilty of a crime. Both Safechuck and Robson spoke in Jackson’s defense in 1993, when the family of 13-year-old Jordan Chandler alleged that he’d been molested. Both parties ultimately agreed to settle the matter out of court. Ten years later, when 13-year-old Gavin Arvizo made a similar claim, a grand jury acquitted Jackson, swayed by convincing testimony from Robson and Macaulay Culkin.

In both instances, and even now, we’ve been asked to believe that Jackson’s intentions with the children filing in and out of Neverland in the nearly 30 years he lived there were pure. He was pop’s Peter Pan. Children shared his bed like friends at a sleepover. The long, and frankly shocking, list of illicit sex acts Robson and Safechuck say Jackson initiated after meeting them as children are likely to be pawned off by many — as allegations from the Chandler and Arvizo cases were in the past — as the work of show moms and grifters extorting a rich and powerful man. The Jackson family cites lawsuits from Safechuck and Robson after the singer’s death as proof that they’re only in it for the money. (The family tried to sue Leaving Neverland out of existence sight unseen, but HBO won’t buckle.) Fans who haven’t seen the film yet are out in force calling both men liars and opportunists. Reed told CBS This Morning that neither accuser was paid to appear in the film.

The prickliness of the history between Jackson and his accusers means that Leaving Neverland might not have the instant believability and stinging finality that Surviving R. Kelly did. There is a chance that people who refuse to accept that Jackson could have mistreated children will continue to do so, because in 50 years in the limelight, Jackson changed culture. He was one of the greatest dancers of all time, full stop. He made incredible music and unusual, engrossing videos. He gave money to charity. He was picked apart by the press for years. If you ever paged through a tabloid in the ’80s, you’ll recall ludicrous stories about “Wacko Jacko.” Leaving Neverland, the logic goes, is just another fabrication.

Just as damning as the allegations is the sense that Jackson lavished these boys with gifts and attention and quickly lost interest as soon as he found new muses. If you don’t believe that Jackson touched anyone inappropriately, you have to reckon with the fact that he knowingly coerced families into allowing their children into his orbit while incrementally driving their parents away; that he nudged them out of the picture as they got a little older, only remembering to call when he needed someone to testify in a court of law. You have to listen to the Robson family explain how Jackson’s machinations pried the young boy’s parents apart, how the singer convinced them to move to Los Angeles from Australia, how Robson’s father committed suicide because they left him.

You come away from the film with the sense that Jackson was, at a minimum, a troubled and deeply manipulative person, more so than we’d ever imagined. The full brunt of the allegations the documentary presents is far more ghoulish. Safechuck and Robson’s stories, and their intersections with Chandler’s and Arvizo’s cases, suggest that the performer not only abused children, but also played his victims against each other through the years. The audacity is unconscionable. Even more painful is the sense that Safechuck and Robson still feel for the man. Leaving Neverland is a film about brokenness and about how pain reverberates through generations, and about how someone could continue to quietly love a person they accuse of having destroyed their young lives. Both accusers planned to take their stories to the grave in the interest of upholding Jackson’s image. Both began to break when they had sons of their own. Both appear to be trying to find peace by breaking cycles. The answer to the question of what they want seems simple. They want closure. They deserve it.

We took too many liberties with Michael Jackson. Too many people thought too highly of him when too much about him was questionable. There were too many children around, too many locked doors, too many secret, guarded rooms in the ranch. As a country, we dismissed Jackson’s accusers too quickly, particularly in the case of Chandler, whose story now seems leagues more damning than I remember. We gave a performer carte blanche to live however he wanted because the music was more important to us than the reports of what might’ve been going on behind the scenes. No one deserves that much power. Safechuck and Robson’s accusations suggest that Jackson’s abuses were specifically tailored around the public perception of him as a man who cared deeply and innocently about children. We should make it very, very hard for this kind of oversight to happen again, regardless of what our personal convictions tell us to do about Michael Jackson’s music and artistry.

I went outside one night this week to catch my breath after watching Leaving Neverland in one sitting. I heard “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” in the wild. I recoiled, half out of remembering the subtle horror of Robson’s methodical phrasing and the image of Safechuck squirming at the sight of a box of jewelry Jackson bought for him, under the pretense that the gifts were for an adult girlfriend. I also felt envy for the people around me who hadn’t seen the thing yet. They got to listen one more time without the dizzying feeling that, all our lives, we might have been sold a bill of goods, that the strange man who made the beautiful music could have been using it to do irreparable harm to innocents in his reach. His music doesn’t give me joy anymore. I don’t know if the feeling will ever come back.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what I feel about what happened, or how the fans feel, or how the family feels. The only people with conclusive knowledge about what went down in those clandestine Neverland rooms are the host and his guests. More than one of them now claim to have been groomed, abused, manipulated, coerced, and coached. That matters as much as the moonwalk, as much as “PYT.” That might make “Heal the World” a lie. That might make the “Man in the Mirror” a monster. You have to overlook a lot of accusations and testimony to continue to maintain unflinching belief in the image of purity and wholesomeness Jackson presented us in his career. It’s a big ask, looking back through the lens of a dark, cynical 2019, where trust is painstakingly earned and easily lost. As the tenth anniversary of Jackson’s death approaches, it’s okay to revisit the memory of Jackson as we thought he was. Let’s also speak of all the aspects of his life we categorically refused to believe, and pledge to never again choose the love of fame over the well-being of a child.