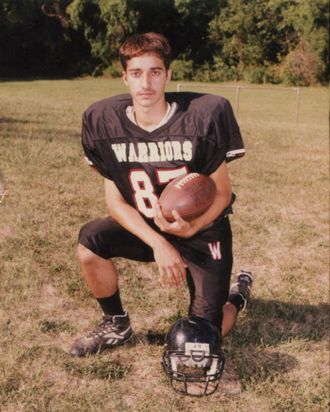

Oscar-nominated filmmaker Amy Berg is acclaimed for her true-crime documentary exposes about the Catholic Church (Deliver Us From Evil), the wrongful conviction of the West Memphis Three (West of Memphis), fundamentalist Mormon leader Warren Jeffs (Prophet’s Prey), and child sex abuse in Hollywood (An Open Secret). But for the past three and a half years, she’s turned her attention to one case made famous by the hit podcast Serial: the 1999 death of Baltimore high-school student Hae Min Lee and the conviction of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed.

Her four-part HBO series, The Case Against Adnan Syed, which premieres Sunday, will follow Syed’s process of seeking and winning an appeal post-Serial. (Though Syed’s original conviction was overturned in 2016, a new trial has been delayed by state appeals. Last week marked the 20th anniversary of his imprisonment.) At a TV Critics Association event last month, Berg said her goal in picking up where Serial left off was to get closer to the truth. “I feel by the end of this, you’ll be much closer to the truth about what did or didn’t happen in this case,” she promised.

For her docuseries, Berg was granted access to Baltimore police, Syed, his defense team, and his family, as well as to friends and teachers of both Lee and Syed. She spoke to Vulture by telephone last week about what motivated her to take on the project, why it’s different than Serial, what she learned about Hae Min Lee in the process, and why she’s pessimistic about Syed getting his new trial.

How did you get involved with this project?

I was a little late listening to Serial. I heard all the hype about it, and then I finally listened to it and I was completely addicted. For me, it felt like the behind-the-scenes of a documentary because you were just seeing how difficult it is to get information. A few months later, I got a call from Working Title Films asking if I wanted to direct a TV doc series of the case of Adnan Syed. And I was just really piqued. One of the things I love about making documentaries is finding out more about something, and I just loved the idea of digging into this. So, I jumped in.

Did you envision that you’d work on it for so long?

No. I thought I was gonna do speed filmmaking, like I always think when I sign on to do anything. And then I realized the story needed a lot more time to breathe, and HBO was great in letting us take our time to find the ending and just really investigate the case for longer. When I started showing them my cuts towards the end of the year, that’s when we thought they wanted to get it on right away.

What was your take on the case when you finished Serial? Were you convinced of Adnan Syed’s guilt or innocence?

I was just really dissatisfied with the information that was available. The whole Jay [Wilds] story was so confusing. “Dissatisfying” is the best word I can use for that. Clearly Sarah Koenig was leaning towards Adnan’s innocence and she got sidetracked by Jay a little bit, too. I was not sure. There was enough doubt for me to want to give this a real close look, and I was very clear with the producers that if I found out anything about Adnan being involved with it, I wanted to go down that road as well. They agreed because there was a lot of “Did he do it, or not?” at the end of Serial.

His guilt or innocence is hard to determine, but it seems most people agree he did not get a fair trial and the police didn’t do a thorough job of investigating Hae’s tragic death.

As a person who does study these kinds of cases — I spent a lot of time on the West Memphis case as well — there are a lot of similarities, in that there’s just not a lot of corroboration beyond people’s statements. And this happened in 1999. There was a certain amount of technology available at the time, and the fact that there were no records pulled that would corroborate Jay’s statements made me uncomfortable with the investigation.

As you went along, did your idea of the case change or shift?

Yeah, of course. It shifted a lot throughout the three and a half years. But there’s a lot missing from this investigation. You can’t just make an assumption that somebody else did it based on that investigation, because they were investigating everything with the idea that Adnan was the perpetrator. When you look at things that way, the story doesn’t have room to move in any other direction.

When you started to think about how to make this different from Serial, what did you think about?

There are a few different aspects that will set us apart from other stories on this subject. Number one is that we picked up where the podcast left off in the current-day timeline, starting with the [post-conviction relief] hearing in February of 2016. And we did our own investigation. We went down a lot of different roads than what some people have gone down. And then, there’s the visual aspect of seeing people’s faces, being in the room with a lot of the voices, as well as the many new voices that we feature in the series.

One of the biggest differences in the first episode is how much we learn about Hae Min Lee. You paint a picture of her that Serial didn’t.

That was one of my first goals, to be honest: to bring the real Hae to life through her friend’s accountings, and hopefully, through the journal entries. I really wanted to make sure that she wasn’t just another victim. Hae was this beautiful young woman who had many things to look forward to in life. I wanted to make sure that we really, really felt her.

How many journals were there?

She started it right before prom, right before she met Adnan, and it ended the night before she disappeared. April of 1998 to January 1999.

What was it like to spend time inside her mind in that way?

It was emotional, for sure. There were things in there that are very personal. She was struggling like most teenage girls are in high school, and she just seemed like this beautiful, passionate woman who lived life to the fullest. She experienced extreme emotions. She fell in love and fell out of love. She was going through a lot at that time. Junior and senior years of high school is a very important time for a young woman. I feel like I learned a lot about her.

Those revelations really put you in the mind-set of being that age. She was so passionately in love with Adnan, and then just as in love with Don in a short period of time.

Yes! Adnan and Hae were still hanging out and trying to be friends at the time. That’s the high-school mind-set. It feels like the case had a very adult narrative — this honor killing, the lover that was left behind, those are very adult thoughts. They don’t happen too often with teenagers unless there’s a history of mental illness or drugs. I did a lot of research on criminal statistics with the FBI and really looked into how this type of murder actually happens in high school and it’s extremely rare.

What was the most important thing you learned about her?

How much she cared about other people. She really, really cared. She was just so passionate. She cared about justice, she cared about truth, she cared about real things. And she wanted a good life for herself. She wanted love so badly. I think she was hurt as a child and just wanted to be happy. That was what Hae was all about. And she seemed like a person who did the right thing. She was a very responsible, very admirable young woman.

Who voiced Hae in the documentary? It really sounded like it could be her. And you used animation to tell parts of her story as well. Can you talk both of those elements?

I had recently seen this film called Diary of a Teenage Girl when I was approached to make this film. I really loved the way the animations were done and how sensitive they were to the teenage struggle, so I reached out to a friend of mine who produced that film and got in touch with the animations artist, Sara Gunnarsdóttir. She’s from Iceland and she’s an incredible artist. We met extensively over the first year and she stayed on all the way ’til the end, fortunately for us, and really brought Hae to life. We wanted to make sure she looked real. We wanted to represent who she really was. And the voice of Hae is, ironically, my junior editor. She had the voice that just sounds very similar to Hae. It was so weird. She just got it right.

Were you disappointed that Hae’s family declined to participate?

Yes. We tried everything. We employed Korean translators, investigators, people who knew her from when she was in Baltimore tried to help us, community leaders. But this is very painful, obviously. We got so close at one point — we spoke to her mother’s current husband and he thought that she might talk to us, but unfortunately, it didn’t happen. There was a spokesperson for the family, a friend of the family who was with them through the whole thing, and she gave us a great depiction of what was going on in that house at the time and the community. That was the closest that we got. It has to be so painful for them that this is coming up again. But if it wasn’t investigated properly and justice was not served, everyone has a right to that trial.

What about Adnan? Like in Serial, we hear him but we don’t see him.

One of the things that makes him such an interesting subject is that his story has never changed and he’s never tried to defend himself. He’s never tried to point the finger at someone else or say something different. And he knows his story isn’t great because he doesn’t know much about that day, because it was just every day for him. So it says something about him that he’s never changed his story.

Did you meet him?

I met him a few times. We had been granted access to film him in the prison, and then it was taken away. We had negotiated access and three days before it was supposed to start, it was just canceled by the State’s Attorney, the prosecutor. I speak to him all the time. I just spoke to him last night.

What did you think of him when you met him?

He’s a very spiritual man. He’s very earnest in person. He feels that the process will work when it works, but not expecting anything to happen very quickly. I think “patient” is a great way to describe him, because you get granted a new trial and then you think you’re gonna get out of prison. It’s been two years since that happened and over two years he said, “Trust me, it’s gonna take another five years.” I think this film will probably be the trial that he gets, sadly. I would love for him to get a new trial.

You feel that way even though he won the right to a new trial?

Yes, because state has the right to appeal every decision until it gets to the Supreme Court, and they’ve used that right twice now instead of just saying, Let’s do it.

Do you think you came closer than Sarah Koenig to solving this case?

I don’t want to give the end away, so I’m gonna skip that question if you don’t mind. I’m sorry.