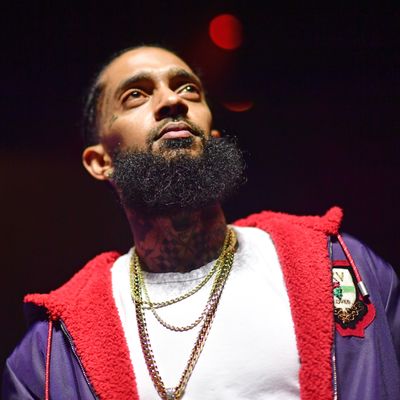

I didn’t always understand Nipsey Hussle’s moves. He made gambles that seemed outrageous. When his talented industry peers were shaking hands with labels to expand the reach of their music, the Eritrean-American, Los Angeles–born rapper went the independent route, self-releasing the majority of his output in this decade via All Money In, the record label he founded in 2010. He bet that he could prove that people still proudly pay to support artists through music by giving mixtapes extravagant price points. In 2013, he sold 1,000 copies of Crenshaw for $100 apiece, including 100 to a notably impressed Jay-Z. The next year, Hussle pressed up 100 hard copies of Mailbox Money and moved 60 of them at $1,000 each. The point that in the twilight of the CD, it was still possible to make decent money cutting the middlemen out of business between musicians and fans is accepted wisdom. From Newark rapper Mach-Hommy to Frank Ocean, artists have followed Hussle’s lead in treating physical releases like onetime collector’s item drops.

Nip also thought outside of the box as a philanthropist and entrepreneur. His streetwear brand and store the Marathon Clothing turned the block he used to hustle on into a legal operation that provided jobs for the community. Vector90, a shared work space and STEM center launched in Crenshaw last winter, made room for young professionals to learn and sharpen skills. Hussle also joined the team behind Destination Crenshaw, a mile-long “open-air museum” set to open alongside a new rail line servicing the area, yet another exercise in putting real money down on neighborhood pride. Rappers say they love where they came from, but Nip used leverage created through music to meet investors and City Council figures in order to grow local businesses and inspire new inventors. There’s shouting out the block, and then there’s pouring time and capital into buying back pieces of it to boost the local economy and aesthetics.

To see Nipsey Hussle gunned down Sunday at age 33 on the street where he set out to make a change in his city is tough to grasp. The youth need guidance, always. They need someone who speaks to them in terms they can relate to about how they can move up in the world. Schools and standardized tests have blind spots, try as the great minds in education might to level the playing field. You’re lucky to grow up with a teacher who cares enough to put you on game, to give lessons normal curricula don’t, to show you how to beat unfair odds. Sometimes you have to get these gems from a complicated figure like Nip. You could tell that he knew this was his calling. On YG’s Trump protest song “FDT,” Hussle acknowledged his role as a voice for people the government often forgets: “I’m from a place where you probably can’t go / Speaking for some people that you probably ain’t know / It’s pressure built up, and it’s probably gon’ blow / And if we say go, then they’re probably gon’ go.” Every time a figure like him passes, it feels like the stars of this generation are blinking out. It’s a loss for fans, friends, family, and the culture at large.

Nipsey Hussle calling his 2018 debut studio album Victory Lap was fitting because it seemed like the pinnacle of his journey up till that point. He took the scenic route to higher ground on the Billboard charts but landed a Grammy nomination for Best Rap Album on his first crack at a formal mainstream album rollout. Even so, there was still room for improvement. Nipsey was getting better at his craft, becoming a more pointed storyteller without sacrificing the subtle, unpolished, conversational tone that made him an instrumental voice in Los Angeles rap. (There aren’t too many rappers in any corner of the country daring enough to touch a “Hard Knock Life” sample, as Victory Lap’s “Hussle & Motivate” did, and make a mark on it.) He was also tangling with questionable thought processes. At times, he entertained conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, sexism, and homophobia. He sometimes shared ideas that complicated his mission of improving the quality of black life by making his message conditional and divisive, feeding into old rifts between straight and queer black hip-hop fans, and between black men and black women. Hussle was far from perfect, but he was trying. His good ideas don’t make his bad ideas less unacceptable. His bad ideas don’t make his death any less tragic.

Gun violence is random and brutal. It only begets more of itself. In interviews and in music, Nipsey Hussle was candid about these realities. He hated to see artists claiming gang affiliations and using the language too loosely. His songs took pride in the life but also stressed about worries and the pain of loss that can come with it. He wanted people to know that street life is nothing to play with and that there’s also more to it than what they read in the papers. A song like “Blue Laces” captures the balance: “They think we on some kill another nigga shit / We really on some stay down and diligent / The streets is cold, turn innocence to militence / Young niggas gangbangin’ for the thrill of it / Pops was gone, moms was never home / The streets was right there so they took you as they own.” Hussle spoke to the risk that comes with the path he walked and the prosperity he found in it, and he worked to make it easier for others. As fans mourned on social media, L.A. Police Commissioner Steve Soboroff revealed that the rapper had recently arranged a Monday meeting between himself, Roc Nation representatives, and local police officials to work out ideas to help curb gang violence in the city.

Days like these raise a chill. On days like these, the game feels rigged. You get dealt a bad hand, you work to make the best of it, you turn your circumstances around, and you can still get murdered on your own block in broad daylight. Anyone who’s ever lost someone who was onto something, who honors the name of a loved one whose promise was canceled by the shot of a gun, can attest. The question of what they could’ve accomplished if one day went a little better never settles. The feeling that calamity always wins in spite of our plans to improve ourselves is hard to shake. It’s tough to know what the way forward is but easy to say what it isn’t. Division isn’t it. Infighting isn’t it. Crackpot theories and misinformation aren’t it. This isn’t a story about how you shouldn’t give back to the hood or an opportunity to antagonize groups you hate or a chance to take someone down a peg to an audience online. We have the rest of the year ahead of us to find reasons to fight. Let’s not make black death a set piece for that. Let’s talk about how to break cycles and get free.