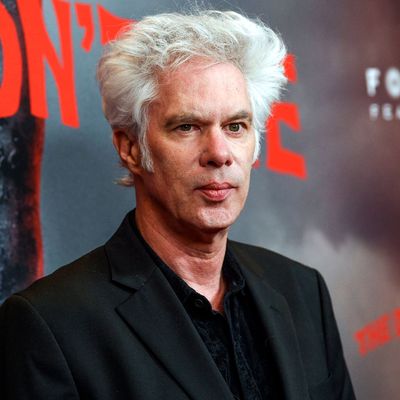

Jim Jarmusch is marveling at the view outside the windows of the hotel room where we meet. ItÔÇÖs odd to think of a man so closely identified with the New York underground and independent film movements being impressed by a view of the Lower East Side, but this room happens to be on a high floor, and the elevated perspective, the director says, is ÔÇ£something new.ÔÇØ I wonder if this is part of his philosophy of appreciating the simple things in life ÔÇö a way, he says, of dealing with the fact that the world is completely doomed. His latest film, The Dead DonÔÇÖt Die, a star-studded zombie comedy in which the undead rise as a result of polar fracking setting the planet off its axis, is another way of dealing with imminent catastrophe. It is somehow both filled with dumb humor and overt metaphoric portent ÔÇö a jarring, unsubtle combination that has divided critics, even more so than most Jarmusch movies. (Our David Edelstein was not a fan. Our Nate Jones sort of was.) The director sat down with us to talk about zombies, politics, poetry, the death of the planet, bad reviews, David Lynch, and his enduring love for teen pop.

I noticed in the end credits [of The Dead DonÔÇÖt Die] that you thanked your first assistant director Atilla Y├╝cer twice.

This was a very, very rough shoot. I donÔÇÖt want to harp on it, but we didnÔÇÖt have enough time. We had to shoot Adam Driver out in three weeks. The first AD is a very, very difficult job no matter what, but he was fantastic. He lived up to his name Attila; heÔÇÖs a real warrior, but so polite. Instead of saying, ÔÇ£Okay, roll camera!ÔÇØ he would always say, ÔÇ£Would anyone object if we roll camera?ÔÇØ Or instead of saying, ÔÇ£Okay, bring the actors to the set,ÔÇØ he would say, ÔÇ£May I invite the actors now to the set?ÔÇØ And sometimes when I would be super-stressed, Atilla would say, ÔÇ£Can you ask me that again with a slightly different tone?ÔÇØ IÔÇÖd be like, ÔÇ£I want the camera moved over there! What are we waiting for?ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Could you try that again in a different tone?ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Atilla, I think we need to place the camera here as soon as possible.ÔÇØ

The general reputation of first ADs is theyÔÇÖre the ones who do the screaming so that the director doesnÔÇÖt have to.

Well, I donÔÇÖt like that militant thing on the set. He was never screaming at anyone, ever. He got screamed at by people. The producers would freak out; some of the actors would freak out. I once read that the Directors Guild has the second lowest age of death of any other occupation, after coal miners in America ÔÇö and this is because ADs are in the Guild, and they take more stress than almost any job you could imagine. Every AD has back problems. They have high blood pressure. TheyÔÇÖre all messed-up. ItÔÇÖs the roughest job on a film.

How and why was this such a difficult shoot?

It took us a very long time to finance it, and we never got the complete budget that we said the film would require. Focus Features were great to us. They gave us total autonomy in every way and totally trusted us, but they were not able to give us what we said the full budget would be. So we went over budget, and in the end, it was exactly the budget we said it would be. And we had very limited time due to the actorsÔÇÖ schedules and the weather. It rained every day. IÔÇÖve always tried to use limitations, to look at them as strengths. All the driving shots with people in car interiors are all on a stage ÔÇö which makes it slightly artificial, which I like. I got walking pneumonia halfway through and had to keep shooting 15 hours a day with blankets and coats, and it was 95 [degrees], you know? I broke my toe; I had to keep working. It was like the Book of Job.

I got such a sense of despair from the movie. Even though itÔÇÖs lighthearted in many ways, it has a sense of overwhelming sadness. Was that on your mind, when you were making it?

I still think of the film as a comedy, very much so. ItÔÇÖs not agitprop. It definitely has a sociopolitical thread in it, which is reflective and therefore dark. But hey, everyone, wake up! WeÔÇÖre in the sixth mass extinction on this planet. To not have that darkness would have been a little superficial. There is a sadness in the human behavior for me, and zombies are the most obvious metaphor you could employ.

We were also trying to make a kind of extension or homage to George Romero because of his postmodern reinvention of zombies [with The Night of the Living Dead and its sequels], and those sociopolitical threads are evident in his films. Romero does a lot of fascinating things: The zombies are monsters, but theyÔÇÖre not Godzilla. They donÔÇÖt come from outside the social order. They come from within a collapsing social order. TheyÔÇÖre us, or any of us who have died, so they are also victims because they donÔÇÖt choose to be undead. ItÔÇÖs because of some stupid shit humans did that caused them to become undead.

But the zombie concept is already so inherently metaphorical. How do you push it further so that youÔÇÖre not just treading old ground?

The problems of mass consumerism, the things that are woven into RomeroÔÇÖs films, have only gotten worse. They havenÔÇÖt changed. So why would you need to push it? WeÔÇÖre at a crisis because of what his films were warning. And now weÔÇÖre at the endgame of that. What is more terrifying than having 1 million species going extinct in the last decade?

You also deny the viewer the traditional idea of suspense and conventions like that. So that weÔÇÖre left facing the metaphorical element straight-on. YouÔÇÖre very in-your-face about what the zombies represent.

There arenÔÇÖt plot twists or formulaic suspense; itÔÇÖs just a progression. And to me itÔÇÖs a character-driven comedy that gets dark. But IÔÇÖm not big on those formulas. Everybody else does that. We werenÔÇÖt trying to make The Walking Dead. I donÔÇÖt know if you saw Train to Busan, the Korean film. That is a badass zombie film. And that has terror and suspense. I love that film for what it is, but this is not that. This is Bill Murray, Adam Driver, Chlo├½ Sevigny as cops in a little town with a lot of ridiculous dialogue. It was intended to leave you with the thought, What a fucked-up world.

For me, having, for example, the hat that Steve Buscemis character wears, which has a slogan, Keep America White Again. Thats a little out of my normal  Im not really into being didactic. But at the same time, [by showing] this kind of racist sloganeering, were reflecting something that is concerning. I didnt want to hide from it.

It was interesting to see you make this film after Paterson, which I thought felt like a very personal film, filled with a sense of awe for the mundane. That movie was like an artistic manifesto: You had come to New York to be a poet initially, and now youÔÇÖd made a film about a poet of the everyday, which is how I think many would describe you.

Well IÔÇÖm a godson, I hope, of the New York School of poets. I studied with Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro, and my bible, when I came to New York, was An Anthology of New York Poets, edited by Ron Padgett and Dave Shapiro. Ron Padgett wrote the poems for Paterson. I love the Beat poets and also Black Mountain and the San Francisco poets, but for me, the New York School, thatÔÇÖs kind of my blood. TheyÔÇÖre exuberant. They embrace all forms of expression: painting, poetry, architecture, anything that moves them. They are very aware of the importance of humor in the poems.┬áThese have been, in a way, my masters as a filmmaker.

You said once that when you start making a movie, it always starts off serious, and then gets funnier as you shoot. Was that the case here as well?

This is a little different. It kind of got darker. It still had the humor in it, but my initial idea was to make a film like Coffee and Cigarettes, and use the zombie-apocalypse structure to get actors that I love in smaller groups, kind of cordoned off against the zombies. And in the lulls, which would be longer than the attacks, they could talk about all kinds of dumb stuff, like in Coffee and Cigarettes.

Something of that still remains, in that everybodyÔÇÖs kind of in their own little world, and each is sort of invaded by the zombies. ThatÔÇÖs also why it feels so despairing. Because no matter who you are, or what your attitude is, or how cool you are, or how big of a racist or a progressive you are, itÔÇÖs coming for you.

Yeah. And it is. The real problem on this whole planet is divisiveness. ThatÔÇÖs the premier tactic of totalitarianism. I donÔÇÖt want to fight against my enemies; I want us to all join together to face something that is not political, which is an ecological crisis. It has to do with our children and our future and our species and all the beautiful things that we have on this planet. So I donÔÇÖt like the divisive thing. When you donÔÇÖt have any water or food for your children, or thereÔÇÖs misery of disease and climate migrations, all of this other stuff is going to be secondary. So we need empathy and togetherness somehow. Because weÔÇÖre all in this together. ItÔÇÖs coming for everybody.

HereÔÇÖs a thing I struggle with, and youÔÇÖre a parent so you probably do, too. How to get through the day knowing whatÔÇÖs happening to the planet and how much worse itÔÇÖs going to be for our children, after weÔÇÖre gone. ItÔÇÖs paralyzing.

ThereÔÇÖs a philosophy expressed by RZA in The Dead DonÔÇÖt Die. RZA and I, we have the same martial arts shifu, and he is very philosophical in a very minimal way because he hardly speaks English. ÔÇ£Even for a few seconds every day or once a week, if you can achieve being in the present moment, the world is perfect.ÔÇØ And if you realize the world is perfect, you do appreciate the details of having a consciousness. ThatÔÇÖs not just throwaway to me. When IÔÇÖm very depressed about human behavior, I get lifted by realizing that I have a consciousness, and what an incredible thing life on earth is, just so brief in the universe.

For me, I donÔÇÖt want to put the fear out. I donÔÇÖt want looming darkness, fear, and paranoia, but I want younger people to be aware. And they are. In fact, the younger people are the leaders now. Greta Thunberg is one of my leaders. Teenagers are extremely important to me in many, many ways. Culturally, they define us, our music, our sense of style.

And although sheÔÇÖs not a teenager, was that why you put Selena Gomez in the film?

Selena Gomez, Austin Butler, and Luka Sabbat are all really fine young actors, super-naturalistic actors, but theyÔÇÖre also incredibly beautiful. So I wanted them to be like these beautiful young people in a beautiful vintage car traveling through the world with all possibilities open. When they land in Centerville, they are like exotic creatures out of a Guess jeans ad.

I loved Selena in Spring Breakers, Harmony KorineÔÇÖs film. I loved her in The Big Short, where she broke the fourth wall and gave a little lesson in economics. SheÔÇÖs a radiant person, and a very powerful, positive force, especially for young females. SheÔÇÖs very strong about body shaming, about not trusting social media, that sort of thing. As well as quite an interesting pop musician. I love a few of her songs: ÔÇ£Bad LiarÔÇØ and ÔÇ£It AinÔÇÖt MeÔÇØ are really classic pop songs. Do you know Billie Eilish? SheÔÇÖs a genius.

What I find really interesting ÔÇö sorry to divert briefly ÔÇö but current pop music is dominated by femininity. ItÔÇÖs all of the stars, whether itÔÇÖs Ariana Grande or Taylor Swift or Alessia Cara or Selena or Billie Eilish. ItÔÇÖs very, very female. Hip-hopÔÇÖs a little harder and dominated by the male thing, though there are great female hip-hoppers, too. Some years ago, I wanted to learn how to play on guitar and sing a song of Taylor SwiftÔÇÖs called ÔÇ£Teardrops on my Guitar.ÔÇØ I just thought, God, thatÔÇÖs a beautiful song. IÔÇÖm not really a Taylor Swift fan, but when you see strong stuff, itÔÇÖs strong. I got about halfway through, and then I never really finished learning it completely. But itÔÇÖs interesting that the very strong pop music that speaks to young people all over this planet is very feminized.

Its been growing for a while. You could say that Madonna was a pioneer in this, and then we had Britney, Christina 

TLC, Britney. At the time I was like, ÔÇ£Gee, Britney Spears. Really? Come on.ÔÇØ Now, I see. ÔÇ£Baby One More Time,ÔÇØ thatÔÇÖs a very important turning point of pop music. I donÔÇÖt know if you ever saw this, but when Britney Spears had a breakdown and shaved her head, one of my teachers ÔÇö one of my heroes in a way, though I donÔÇÖt like that word ÔÇö Jonas Mekas said, ÔÇ£Hey, get off Britney SpearsÔÇÖs back.ÔÇØ He had a picture of her with her head shaved, saying, ÔÇ£She is an artist. I donÔÇÖt care what you think of her art; she is an artist. It comes out of her soul. Give her a break. All artists are susceptible to a breakdown because of what they give us.ÔÇØ Jonas Mekas, the king of experimental, avant-garde film, standing up for Britney Spears. I thought that was really beautiful.

How closely are you following the election?

Since Joe Biden entered, IÔÇÖm avoiding it because thatÔÇÖs distasteful to me. The lesser of two evils does not appeal to me, and I donÔÇÖt like the two-party system anyway. I donÔÇÖt know why people arenÔÇÖt all over the Electoral College and this nonsense. Well, I do know why, because itÔÇÖs the corporate media. What disturbs me now is that my friends who donÔÇÖt like Trump spend maybe more time on Trump than the people who like Trump. Trump sets the content for the corporate media every day, and by corporate media I mean MSNBC and CNN and Fox. TheyÔÇÖre all the same; itÔÇÖs just the Trump channels. I like some things about Elizabeth Warren. I, of course, like Bernie Sanders. I like whatÔÇÖs his name, the governor of Washington State whoÔÇÖs the only really environmentally conscious one [Jay Inslee]. And, of course, I like AOC; sheÔÇÖs too young. But IÔÇÖm trying to stay away from it right now because the Joe Biden thing makes me deeply depressed.

Do you read your reviews?

I try not to. I really love bad reviews, so I read the really negative ones. I carried in my wallet for years a clip from, I think, Le Figaro, of my film Down by Law in Cannes, and they said ÔÇö IÔÇÖm translating, but I even laminated it ÔÇö ÔÇ£The French intelligentsia praises Jarmusch in the way a deaf and blind parent would applaud their retarded child. Jarmusch is 33 years old, the age Christ was when he was crucified. We can only hope the same for his film career.ÔÇØ I loved that one, man!

YouÔÇÖve gotten some bad reviews for this one.

WeÔÇÖve got some, especially from the trades. I read a few. I read the Variety one. I also know hard-core horror nerds may not like this film. Trump people arenÔÇÖt going to like this film, and thatÔÇÖs a lot of people already. We didnÔÇÖt build the film to be a money-making machine, so theyÔÇÖre probably going to say, ÔÇ£Not a money-making machine; it sucks.ÔÇØ WeÔÇÖre apparently really strong in France. And we apparently got nice things here, in Time and The Wall Street Journal, places I wouldnÔÇÖt expect. I did read the nice thing by Richard Brody in The New Yorker, where they have the little picks.

What are the films you watch these days?

Oh boy, I watch a lot of films. I saw a lot of beautiful ones that were almost mainstream last year, like Roma and The Favourite. I really liked, except for the music, At EternityÔÇÖs Gate, Julian SchnabelÔÇÖs film with Willem Dafoe. I liked High Life, a very strange Claire Denis film. I liked Shoplifters, BlacKkKlansman, Death of Stalin, Minding the Gap. Oh, the best of American cinema of the last decade, probably, for me, is Twin Peaks: The Return, an 18-hour film that is incomprehensible and dreamlike in the most beautiful, adventurous way. That is a masterpiece. Why canÔÇÖt they just give David Lynch whatever money he needs? Why canÔÇÖt you give Terry Gilliam? He needs money to make something; just give it to him! I donÔÇÖt understand.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.