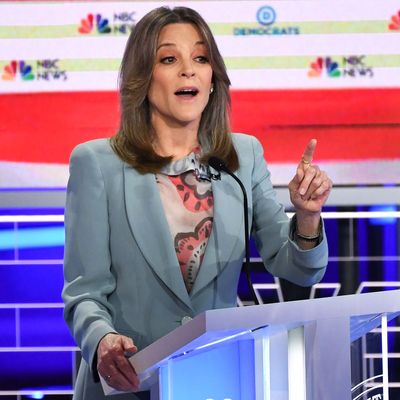

When Marianne Williamson first spoke, approximately half an hour into Thursday night’s Democratic candidates debate, I recognized her immediately. Not as a specific person, because I have never seen her before and have only the scantest sense of who she is or why she was even on that stage, but because I immediately recognized her as a TV character type. She is the person in the earliest episodes of a competition reality show who’s there so the producers can drum up silliness before they have to pick between the real competitors. She’s the wacky sideshow, the one everyone looks at askance. She’s the Bachelor contestant with “bird lover” on her identifying chyron, while everyone else’s says “realtor” or “professional athlete.” She is there to be made fun of before she is inevitably eliminated.

By now, the idea that we view politics through a reality-television lens is well-trodden territory, a familiar line of analysis that’s often thrown out as an easy line of punditry. But during the two-night Democratic debates this week, the parallels were nevertheless hard to ignore, because the experience was like nothing so much as the early episodes of a dating reality show like The Bachelor. The front-runners have been largely preselected by the producers, and everyone else onstage is flattened into minor character status.

Williamson’s not alone in this. In the first night of debates, there was Tim Ryan, the guy who appeared flabbergasted to even find himself in this position and who confused the Taliban for Al Qaeda. There was Beto O’Rourke’s awkward Spanish-speaking interlude, a moment that only served to remind everyone that O’Rourke comes off as the guy in high school who knows what it looks like to be a good student, but does not know how to be a good student. There was Andrew Yang on night two, who distinguished himself by rarely speaking and hyping one of his unusual signature policies (a $1,000 “freedom dividend” paid to every American), without much room to explain how it defines his larger ideology. Bachelor contestants try to stand out from a crowded field by bringing strange props, riding in on horses, or reading terrible self-composed poetry aloud. In a debate like last night’s, Yang’s freedom dividend was the equivalent of getting out of a Bachelor limo dressed as a dolphin.

The idea of Trump as a reality-TV show president is rooted in his years on The Apprentice; calling him a reality-TV personality is literal in a way it will never be for any other candidate currently running in 2020. But the idea of characterizing the current slate of candidates as reality-show competitors, of seeing them as character types analogous to various Forged in Fire competitors, or Survivor strategist types, or Real Housewives, is in part an unavoidable frame created for them by the simple act of being on that stage, within a ten-person debate platform where they are not treated as remotely legitimate. They’re onstage because they have qualified to be there and are desperate for the national attention, but they get less time to speak, they are situated at the visual margins of the screen, and their minor-ness is reified every time they do actually get a question and end up looking vaguely shocked to even be addressed. They are cast as types not by their personalities (although Williamson’s Twitter feed suggests that her debate performance is absolutely reflective of her true self), but by their presence in debate that has been structured and produced as a format with a group of preselected protagonists.

(That said, some of them are also reducible to reality-show types entirely on their own power. Tulsi Gabbard is absolutely the kind of person who’s a friend of a Real Housewife, shows up at one dinner party, and says several weird things that act as a springboard for the rest of the housewives to start bickering.)

The problem, of course, is that when this same structure played out in 2016, Trump held a similar position as someone like Marianne Williamson. He was the strange, arresting performer that everyone wanted to talk about, the one nobody took seriously, the one who captured attention within a massive field of candidates despite his demonstrable unfitness. He was a minor character who forced his way into the narrative center by the force of his sheer magnetic awfulness. It’s a reminder that treating candidates as characters rather than political figures runs the risk of making them do what good characters do: become compulsively watchable. Weirdo Bachelor contestants often go on to have lucrative careers as major franchise personalities on spinoff shows, as spokespeople for spon-con, and as paid personalities to hype events. So meme Marianne Williamson if you must, and enjoy the Kate McKinnon impression, but do not forget that weirdo minor characters can have unexpected staying power. If the producers realize she’s a fan favorite, she may stay on this show for many more weeks than anyone actually wants.