Warning: Spoilers for Godzilla: King of the Monsters follow.

When Godzilla rebooted in 2014, it became the first entry in Legendary’s newly minted “MonsterVerse,” a world in which a giant aquatic lizard and a giant island-bound ape are both sort of benevolent. (Let’s just say they stand on the side of the humans against a small contingent of massive terrestrial organisms who seem less enthusiastic about their earthly cohabitants.) But in the grander scheme of things, there are over 30 films in the Godzilla franchise that Japanese studio Toho kicked off way back in 1954. That means Godzilla and Kong are just the tip of Legendary’s nuclear-allegory iceberg. There are, I feel confident in saying, far more monsters within the Godzilla universe than you ever dreamed possible.

Enter Godzilla: King of the Monsters filmmaker Michael Dougherty, who was tasked with fleshing out the world that Gareth Edwards established five years ago and that Jordan Vogt-Roberts built upon in 2017’s Kong: Skull Island. The question ahead of his 2019 movie was: Which of the larger franchise’s many, many monsters would battle MonsterVerse’s king? It wouldn’t be Kong (we’ll have to wait until 2020 for Godzilla and the ape to face off in Adam Wingard’s Godzilla vs. Kong), but would any of Toho’s Big Five make their way to the screen again? Which would Dougherty choose?

One of the hardest decisions, it turns out, was actually simplified for the filmmaker best known for directing Krampus (no word yet on if or how Krampus fits into the MonsterVerse): Before he took the helm, Legendary had already licensed three of the so-called Big Five characters — King Ghidorah, Mothra, and Rodan — from Toho. While there wasn’t exactly a mandate to use them, Dougherty, a lifelong Godzilla fan, says he was more than happy to focus on the foursome in his script.

“Those are very much the crown jewels of Toho,” Dougherty says. “They were the original giant monster team-up, so it only made sense that they would be the ones we would update for this particular entry.”

Dougherty & Co. (he shares the screenplay credit with Zach Shields, his co-writer on Krampus, and the story credit with Shields and Max Borenstein, one of the writers on Godzilla and Kong: Skull Island) crafted the film’s plot around two parallel conflicts: One between the secret monster-tracking agency Monarch and a team of ecoterrorists led by Charles Dance’s Jonah Alan, who is hellbent on restoring a natural order of monsters, and the other between Monster Z (who, it’s revealed, is Ghidorah) and the kaiju fighting on the side of GodZ.

Unfortunately, adding any other kaiju besides Ghidorah, Mothra, and Rodan, even in cameos, would’ve cost a relatively steep licensing fee. Dougherty loves the fifth member of the Big Five, Mechagodzilla, but he wasn’t about to squeeze him into the MonsterVerse just yet. “Mechagodzilla is a personal favorite because it’s just bonkers,” he says. “It’s such a bizarre concept to create a giant, cyborg, robotic Godzilla. Sure, why not? It was the ’70s. Go for it.”

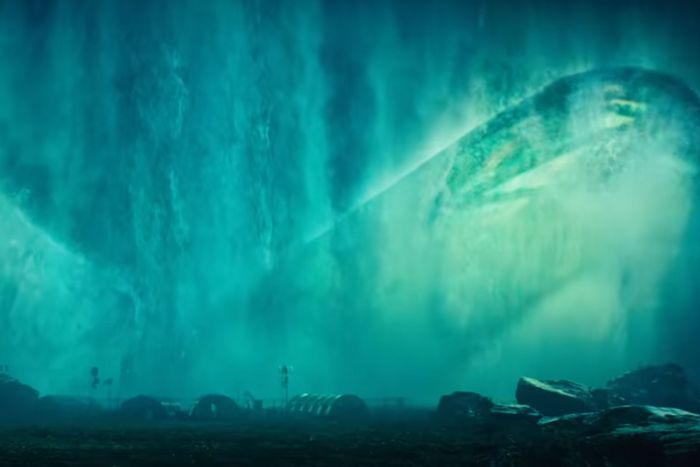

Once Dougherty had his monsters, it was time to render them into nine-figure-budget versions of themselves. King Ghidorah, Mothra, and Rodan have distinctive qualities they’ve maintained across decades of Toho appearances, and Dougherty worked to build his versions around the same traits. For example, King Ghidorah always has three heads, golden scales, and two tails; Rodan always has a “reddish burgundy-maroon” hue and a penchant for volcanoes; and Mothra has always been colorful and furry.

But Dougherty wanted to make his creatures distinctive in some way. Whereas Edwards made the sheer spectacle of Godzilla the focus of his film, hiding him until about halfway through the movie and then doing everything he could to showcase just how huge the monster is, Dougherty takes a different approach. After all, the cat’s out of the bag; we’ve seen Godzilla and Kong. We get it, they’re big boys. Instead, the director decided to focus on something just as jolting: sound. When Dougherty went back through old Toho movies, he was impressed by how each monster is bestowed with his or her own voice. “The roars of the creatures are so iconic,” he says. “They make very particular sounds, and they always have.”

(This observation forms a significant part of the new film’s plot, which includes a device called the Orca that can replicate the monsters’ individual cries.)

Dougherty tried to channel the monsters’ personalities, too. In crafting the story and shooting the film, he made a concerted effort to treat each one as a character, not just a special-effects piece, and he based these characters around the essential elements that have defined them since their beginnings. “Mothra is sort of the yin to Godzilla’s yang,” Dougherty says. “She’s very bright and she’s always seen as a very benevolent and kind protector, but she’s not afraid to throw down when necessary.” In King of the Monsters, she does indeed protect Godzilla, sacrificing herself so that he can live to fight another moment against Ghidorah. (Whether Mothra is truly dead depends on how you interpret the movie’s final scene.)

“King Ghidorah is always, or not always — every now and then King Ghidorah has been a good guy, strangely enough — but generally he’s a nemesis, very vindictive and destructive,” Dougherty adds. “And then Rodan is a bit of a rogue. As far as his personality goes, he’s unpredictable; sometimes he’s an ally to Godzilla, sometimes he’s an enemy. But he’s kind of crazy: He just enjoys a good barroom brawl.”

Dougherty tried to make the four nonhuman stars feel as present as possible by playing their cries around the actors on set — a technique inspired by the story of William Friedkin’s firing off a gun loaded with blanks on the set of The Exorcist. Dougherty believes it evoked a sort of primal-ape-mind reaction from the actors, a throwback to the time when the cry of a saber-toothed tiger meant you’d better get running. Dougherty believes the essential appeal of the Godzilla franchise lies in this ancient connection between man and monster; it’s what makes these rebooted sagas feel so poignant 60 years later, he says, particularly as the threat we pose to the natural world only grows.

“I think humans are a very arrogant species, and we tend to make a lot of our stories simply about ourselves and our tiny struggles, but Godzilla came along and shifted that dynamic,” Dougherty says. “They say, ‘Now we want you to identify with a 400-foot-tall ancient monster,’ and we did, we embraced him, and I love that.”

While the MonsterVerse might share the increasingly crowded cinematic-universe space with the likes of Marvel and DC, for Dougherty, this factor highlights a stark difference: “Godzilla movies reinstill my faith in humanity because they do ask us to identify with an animal as a hero instead of simply another guy in a cape.”