Across a swath of cleared farmland, framed by towering coniferous trees, sit a series of ten, eerily timeless pinewood buildings. Three watchtowers loom overhead, a searchlight affixed to each. Ten-foot-high barbed-wire fences corral the grounds. This is season two of the AMC anthology series The Terror, where the story unfolds at a Japanese-American internment camp, a facsimile of which was built across seven acres of land an hour south of Vancouver.

The setting is a fictional camp based in Oregon that’s a composite of the structures where Japanese-Americans were forcibly relocated during World War II. But in co-creator and executive producer Alexander Woo’s supernatural retelling, it’s also haunted by a spirit named Yuko (Kiki Sukezane). Throughout the ten-episode season, subtitled Infamy, she haunts the residents of the Japanese-American community of Terminal Island, California, none more so than the protagonist, Chester Nakayama, played by Derek Mio. Woo (True Blood), who executive-produces The Terror alongside Max Borenstein (Kong: Skull Island), told Vulture on set in June that he wanted a being that could symbolize the nightmare that was the prison-camp experience. He was inspired by kaidan, a Japanese ghost story that often features a yūrei, or a vengeful specter, as seen in movies like The Ring and The Grudge. “She’s an alien presence even within this community of Japanese-Americans,” Woo says. “We don’t exactly root for her, but we understand where her rage comes from.”

At the end of the first episode, the Terminal Island residents are treated like aliens, too. The military rounds them up and they’re sent to a prison camp in northern Oregon, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which brought the U.S. into World War II and ushered in the nuclear age. Woo says the scene is an accurate depiction of the anti-Japanese hysteria surrounding the executive order by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, which forcibly sent 120,000 people of Japanese descent — most of them American citizens — to ten camps nationwide.

Behind the scenes, the story was personal for some of the cast, too. Mio’s grandfather was from Terminal Island and was sent to Manzanar internment camp in California. For George Takei, who plays community elder and fisherman Yamato-san, much of the show was true to life. In 1942, his family was sent to live in horse stables before being transferred to a camp in Arkansas when he was 5 years old.

“The emotions of what George Takei and all the other people who lived through this feels like a horror movie,” Woo says of the choice to depict this era of history within the genre. “It wasn’t like, ‘What can we do to make this scarier?’ It’s scary.”

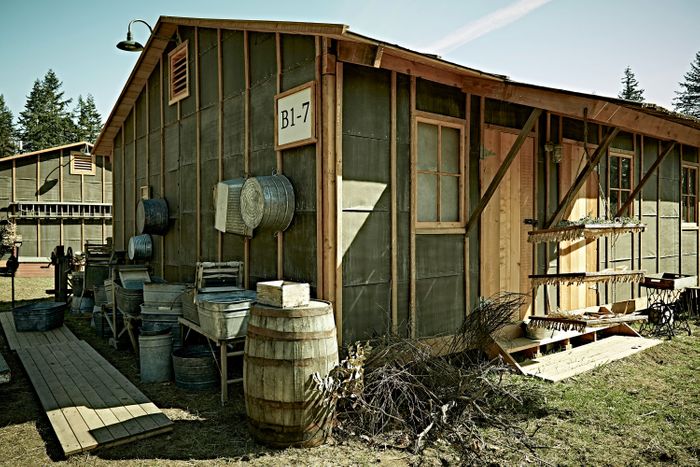

Indeed, just walking through the plot of land used to create the camps feels cold and unwelcoming — the series of uniformly designed buildings that include 120-foot-long barracks made of pinewood and tar paper, an infirmary, a stockade used for punishment, an administrative unit, an infirmary, and the watchtowers. (A green-screen and visual effects then made the camps look larger in scale onscreen.) But if you look closely, there’s warmth in the surroundings, too. Production designer Jonathan McKinstry (Love Actually, Penny Dreadful) paid particular attention to bringing in details that made it feel like the characters had made a home here.

McKinstry spoke to Vulture about the process of honoring the story, erecting the camps, and creating a sense of dread for the horror anthology.

1. First, research.

Woo says the team talked to internment-camp survivors from places such as Heart Mountain in Wyoming. They told them tidbits about the camp and the surroundings, like the fact that prefabricated buildings could be put together by troops in as quickly as an hour and a half. The teams also studied renderings from Manzanar internment camp in California. The barracks were designed to show that about 50 people were living within one unit. McKinstry says he redressed the structures to include different setups for various scenes — barracks for single men, women, and families, for example.

2. The right setting.

It was a bit of a struggle to find a location that would allow building permits and was within range of the rest of the Vancouver-based set. “We were at the 11th hour when we finally found this location,” McKinstry said. The team started working on the camp location last December but began pre-fabricating in September.

The crew also had to contend with Vancouver weather. Two weeks before they started shooting a spring scene at the camp, there was about two feet of snow. The Location, Construction, and Greens teams scooped up snow with machinery and then set out heaters to melt it. (It was a success.) There was concern it would snow again the day before shooting, so they had helicopters ready to blow snow off the trees in the early morning, which, as the team explained, is less expensive than using effects.

3. A period-specific color palette.

Generally throughout the season, McKinstry says he played with subdued colors and a red and green palette — red to represent blood, and green because it’s the color of Yuko’s kimono. The camps are mostly wooden and neutral, with splashes of color throughout, found on props like checkered blankets or floral sheets. “They’re both sort of period colors that work for the 1940s,” McKinstry said. “In the 1940s, they didn’t have the color range we have today. Paint manufacturing was much more complex, so there was much more limited range of colors available. So quite often if you use a color that’s not period correct, it doesn’t feel right.”

4. An omnipresent feeling.

The crew laid out the camp in a grid format, complete with gravel, telephone poles with wires, and loudspeakers on poles to issue public statements and enforce a night curfew. Guard towers had spotlights and patrol windows to keep an eye on the camp. “We played up the searchlights going around at night, invading their privacy, always creating a feeling like they were being watched,” McKinstry said.

5. Eerie uniformity.

The camp is made to look barren, impersonal, and regimental at the beginning, with the labeling on the barracks depicting the families as just a number. There are offcuts of timber lying around, set against empty sheds. They are prisoners with no freedom, and McKinstry says he wanted to create a sense of universality to these scenes. “With people detained against their will all over,” he said, “this story is always relevant.”

Then, throughout the season, McKinstry introduced features like bamboo partitions, handmade wind chimes, and small plots of land that grow both kale and bonsai. “I wanted to show the resilience of the Japanese-American people and what they did to make it feel like home with whatever limited resources they had, but not to diminish their hardship and experience.” He outfitted each doorway with a few personal effects, like signage with family names, and re-created checkers sets that used rocks as game pieces and small, makeshift cemeteries with Shinto and Buddhist shrines. To create family photos, McKinstry relied upon real-life photos and artifacts from Takei, who also consulted on details as small as the look of the mismatched, broken plates in the mess hall.

Woo points out that while there have been documentaries, plays, and other pieces, nothing of this scope has been devoted to the story of Japanese-American internment. “It’s one of the strengths of television — you can get into the skin of these characters,” Woo said. “Viewers are living with it for three months. You can’t just turn off the end of internment of Japanese-Americans, especially because they returned to a country that didn’t want them. A series was a closer analog for what really happened to them.”