David Koepp hasn’t just written a new novel about killer fungus — he’s spent his summer fighting off hostile plants, and he’s got the scars to prove it. “Have you ever heard of Asiatic tearthumb?” he asks, his arms propped up on the table at an Upper West Side eatery, his forearms bearing a criss-cross of bright-red scratches. “It’s native to more southern climates. It was never in New York until Hurricane Sandy. It’s also called ‘mile-a-minute’ because it grows so fast — it can grow six inches in a day.” Koepp has been battling the invasive weed at his summer house in Amagansett. “The roots are horrifying. They’ll run like ten feet sideways through the soil. These —” he says, referencing the scratches, “— are from before I figured out you need to wear long sleeves and long pants.”

Koepp, who’s 56, has spent the last 30 years as one of the most successful screenwriters in Hollywood; among his three dozen or so high-profile credits are Jurassic Park, Carlito’s Way, Panic Room, the first Mission: Impossible, and Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds remake. (This may help explain the summer house in Amagansett.) Tall and thin, with more than a passing resemblance to Matthew Modine, Koepp displays a classic Midwesterner’s wry mien, and his biography is so capital M Midwestern that, if he were a character in one of his own movies, his backstory might seem too on-the-nose. He grew up in the 1970s in Pewaukee, Wisconsin, the son of a therapist (his mother) and a billboard-company owner (his father).

During that formative age, “from 14 to 24, when all your tastes are shaped,” he recalls lying around on his family couch, falling in love with all his now-favorite films and books. The films? The Bad and the Beautiful, for one, but basically everything that came out between 1979 and 1982: Alien, Being There, Kramer vs. Kramer, The Empire Strikes Back, The Shining, Raging Bull, John Carpenter’s The Thing, E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Altered States. And the books? “There were two authors that were really big for me, Stephen King and Kurt Vonnegut.” The latter was a chance discovery, but an all-important one: “I picked up Player Piano at random because I liked the cover, so I sort of lucked into the one author who was considered great literature and also wrote in science-fiction. I think I developed a humanist viewpoint thanks to Vonnegut and [Doonesbury cartoonist] Gary Trudeau.”

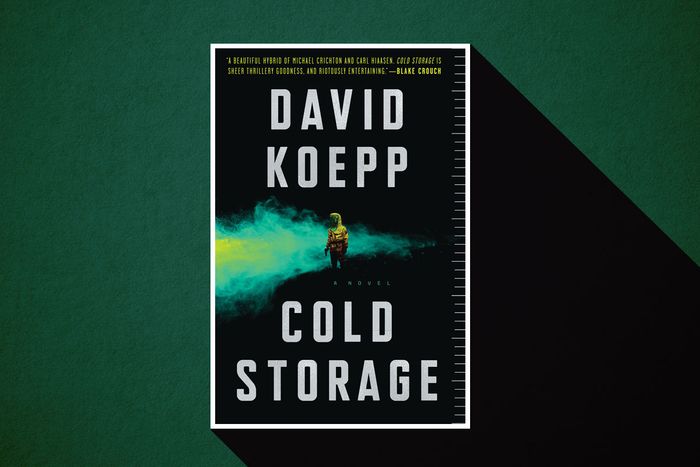

This set Koepp on the slightly crooked path of becoming a humanist-horror fan, leading him from Wisconsin to UCLA and, eventually, Hollywood. Humanist horror is also a pretty good description of his first novel, the thriller Cold Storage, which is out today. Along with the aforementioned killer fungus, it features a bunch of very scared humans. Christened cordyceps novus, the fungus is a fictional spore that mutated in outer space, came back on the crashed space station Skylab, hibernated for decades in the Australian outback, and is about to devour the world. As you might expect from the screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Mission: Impossible, the novel starts with a grandiosely cinematic set piece: Grizzled military operatives approach Australia in a transport plane, accompanied by an attractive scientist playfully named “Hero,” and encounter a scene of nauseating horror and — well, this is the beginning of the book, not the end, so let’s just say they do not initially succeed at wiping out the fungus.

What happens next, though, is not what you’d expect from the screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Mission: Impossible. Rather than race full speed into global eco-horror, with obligatory pit stops in world capitals and secret Pentagon war rooms, the novel instead becomes a claustrophobic and genuinely touching story of two hapless low-level employees — a security guard nicknamed Teacake and a single mother named Naomi — who are stuck as wage slaves in a storage facility in rural Kansas. One night they hear a strange beeping just behind the wall and, being bored, decide to investigate — to their eventual regret.

For Koepp, it was both a pleasure and a relief to escape the increasingly stringent rules of blockbuster screenwriting — not to mention the cavalcade of intrusive producers’ notes that any big-budget film entails. “I found this really deeply satisfying in a way that movies can be only rarely,” he explains. “Movies, at best, even if you write and direct it, you’re part of something that’s highly dependent on other people having a good day at work.” Screenwriters are primarily responsible for producing a blueprint for a finished film, leaving little room for whimsical detours or, really, anything that doesn’t keep the narrative rocketing along. “I was fascinated by being able to digress!” he says. “I mean, 30 years of screenwriting do something to you that you can’t undo, so the novel moves pretty quickly. But as a writer you’re really able to lose yourself in a way that you can’t in a script because you can go inside somebody’s head. Also, I like solitude. And you certainly get a lot of that.”

The notes he got from his editor “were so gentle and intelligent,” he says. “I thought, This can’t be! I’ve never had that experience [in screenwriting]. Some people are nicer than others, some people are more encouraging than others, but no one views the script as essentially yours. They view it as essentially theirs.” The novel, he realized, was essentially his.

This, of course, is slightly terrifying as well, as there’s no one else to hide behind if it doesn’t land. Being a successful screenwriter definitely helps you to, say, sell your novel, and it definitely helps sell the screen adaptation of your novel, which Koepp already has done, and will write himself. But it also comes with a potential downside. As he worked on the novel, he says, “There were two things I was afraid of. One was, to spend a really long time on it and not even get it in print. The other is public humiliation, which I never enjoy.” He chuckles. He’s Midwestern. “I’ve had my share of it. Movies are a public thing. And I know that ‘screenwriter with some hit movies who tries to write a novel’ is not …” He doesn’t finish the thought, but refers instead to a scene from Jack London’s novel The Sea Wolf, in which a cook, hoping to intimidate a young boy, simply sits on a nearby stool and sharpens his knives on a whetstone. “That’s how I picture what’s coming,” he says. (A recent rave in the New York Times may have allayed his anxieties.)

The desire to write a novel was precipitated in part by the fact that, as tends to happen over 30 years, Hollywood has changed since he arrived, and so has he. The studios of today are much more likely to reboot a franchise like Jurassic Park than to green-light the next Jurassic Park, let alone a movie like Kramer vs. Kramer. “When I came up in the early ’90s, most studios made 25 to 30 movies a year,” he says. “This is no breaking news, but now the middle is largely gone. As a screenwriter, if you don’t particularly want to work on a superhero movie or a Star Wars movie, you’ve just eliminated 70 percent of studio development. And I like those movies! I’ve done those kind of movies! But I don’t want to do them forever and my interests are a little different now.”

In addition to his screenwriting work, Koepp has directed six feature films — in fact, he’s finishing one up right now — none of which have been huge hits, some of which have done well “and I’ve been proud of” and one of which was “a spectacular bomb in all ways imaginable, financial, critical, commercial.” I ask him to clarify. He answers wryly, “I don’t say its name anymore.” (If you check out his IMDb page you can probably make an educated guess.) “All of us miscalculated,” he says of that project. “You don’t do it on purpose! People get really mad when a movie’s bad. I swear, we don’t do it to irritate you. I always thought the perfect wrap-party gift would be a T-shirt that says, ‘It seemed like a good idea at the time.’”

He’s enjoyed the novel writing experience so far — “those were great days at the office” — which is fortunate because he’s already under contract to write another one, a similar thriller that isn’t, however, a Cold Storage sequel. Not that he’s completely exhausted his fascination with killer botany. There’s still Asiatic tearthumb to defeat. “I’d like to do a movie about a 78-year-old guy who fights the vines in his backyard,” he says. “And make that a horror movie. When he pulls the vine out of the tree, there’s a mouth attached to the end of it.” He’s joking — sort of. No sooner has he proposed the idea than he pauses and, as an earnest aside, adds, “That might be kind of fun.”