One of the most fascinating aspects of superhero fiction is the ease with which a character’s initial creator can become its least important author. Monthly comic books have been and continue to be the genre’s womb, and they’re a fundamentally iterative medium. As the years and issues wear on, the writers and artists who conceive of characters frequently leave their creations behind, only for new folks to pick them up and run with them. That often means the first version of a figure isn’t nearly as resonant with audiences as a subsequent one, which might take that figure’s core ideas and tweak or overhaul them so that they really sing for an audience.

There are well-known examples of such character arcs among the good guys: Martin Nodell invented the Green Lantern in the 1940s, but the only reason you’ve heard his name was due to a complete reimagining of his world in the ’60s by John Broome and Gil Kane. The X-Men originated in a 1963 comic written by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, but it was only with the arrival of writer Chris Claremont more than a decade later that the mutants truly crystallized into the versions that are currently famous. The reason Daredevil has had a movie and a TV show is because Frank Miller reinvented him in the ’80s. And so on. But the same thing can happen with villains: Mister Freeze was a tossed-off gimmick until Batman: The Animated Series made him a tragic figure; Magneto gained a core component of his character when he was retrofitted with a Jewish identity; and, perhaps lesser known than the others, there’s the rebirth of the Joker.

Nowadays, one tends to think of the Clown Prince of Crime as — to borrow a term from video games — the Final Boss of the Batman mythos. He is, as Neil Gaiman put it in a comics story a decade ago, the White Whale to Batsy’s Ahab, the Moriarty to his Holmes. Where Batman pursues a near-fascistic vision of order, the Joker is what Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight refers to as an “agent of chaos.” The two are matter and antimatter, oil and water, an unstoppable force and an immovable object, a mythic hero and a trickster god, or any number of other overwrought metaphors.

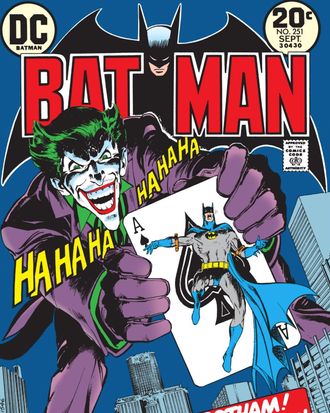

While you can certainly tell great stories with other entrants in Batman’s rogues gallery — Two-Face, Catwoman, Poison Ivy, what have you — none of them fascinate the hero and his readers the way the Joker does. There’s a reason he’s the first of DC Comics’ Caped Crusader’s antagonists to get his own movie, which comes out this week: His wanton murderousness is the platonic ideal of everything Batman struggles against. And yet, it was not always thus. In fact, it wasn’t until a now-obscure story was published in 1973 that the Joker turned a corner and started to become what he is now. The tale is called “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge” and it appeared in the 251st issue of Batman, which hit stands in July of that year. Written by Denny O’Neil and drawn by Neal Adams, it is one of the most important Batman stories ever told.

Prior to its publication, the Joker was just another Bat baddie. Granted, he debuted in the first issue of Batman back in 1940, but that series was actually only the second one to star Batman, popping up after the protagonist’s own debut in Detective Comics the previous year. Accounts of Joker’s creation differ wildly, as is sadly common for so many figures in the petty, fly-by-night world of superhero comics. Each member of the trio of Batman mythos’ founding fathers — the late Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson — at one time admitted that the Joker had been partially inspired by actor Conrad Veidt’s portrayal of a man cursed with a permanent grin in the 1928 film The Man Who Laughs, based on the novel of the same name by Victor Hugo. However, the three men emphasized their own respective contributions when recounting the origins of Joker, often at the expense of one or both of their colleagues. The details get wonky; you can read more in the remarkably detailed Wikipedia entry on the matter. Robinson would eventually claim that he’d always aimed to have Joker become Batman’s archvillain, but the fact is that the character never really ascended to that role until decades after his creation. He appeared regularly in Batman comics, but was no more memorable than other gimmicky bad guys.

In the late 1960s, a campy TV adaptation of Batman featured actor Cesar Romero in the role of Joker (we would do well to remember that this means the villain was once played by a Latino), but Romero’s version similarly blended in with the rest of the show’s murderer’s row. In the 1966 movie that emerged from the series, he was merely part of a coalition of villains. The Joker was still just another antagonist, one with the dull twist that he looked and acted like a clown. To make matters worse, the Batman of the early ’40s to the early ’70s wasn’t an especially grim or gritty character — the hero brimmed with sunshine in that age of comic-book self-censorship.

But the whole gestalt of Batman began to change on a fundamental level in 1969. That’s when O’Neil and Adams took the reins of the character, tasked by editor Julius Schwartz with taking the hero back to his dark roots after the collapse of the bright TV show. The pair were already famed in the world of comics and they wasted no time in their mission to bring Batsy back into the shadows. They specialized in villains, cranking out a run of stories that introduced the tortured mutant Man-Bat and the ecoterrorist mastermind Ra’s al Ghul, among others. But an order from Schwartz made them roll their eyes.

“At some point, our editor, Julie Schwartz, basically said, ‘You know, guys, we gotta bring in the clowns,’” Adams recalls. They were headed in a direction of realism when they were told they had to resurrect a historically goofy lineup of past Bat stories. “So what do you do with a Joker?” Adams remembers them asking themselves. “Well, we took a harder edge. We decided that Joker was just a little crazy.” Prior to that, Joker hadn’t really been given much in the way of motivation or nuance; he was just a guy who liked committing crimes in a silly fashion. O’Neil — who couldn’t be reached for comment — and Adams were the first to make the decision: Joker would be a homicidal, mentally unstable maniac. They didn’t explore his origin story, but they would suggest through his actions that there was something innately wrong with him that made him lethally dangerous.

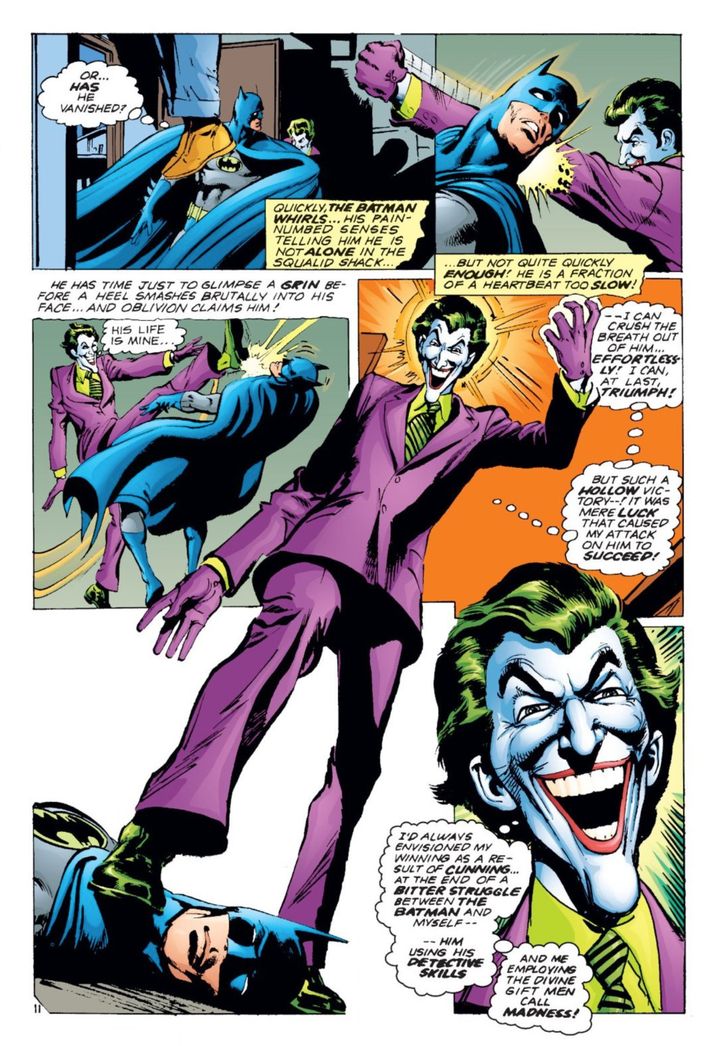

What O’Neil and Adams arrived at — as one might expect from the title of that 251st issue — was a story of revenge. It was established from the very beginning that theirs was a harsher Joker saga than any before it. Open the comic and see a full-page panel of the Joker’s cackling rictus as he drives a vehicle, complete with ominous narration the likes of which had never been associated with him: “From the darkness of a country road somewhere north of Gotham City … and from the greater dark of a past filled with evil … comes a terrifyingly familiar face! Thunder racks the earth and lightning scars the sky and wetness streams from the clouds like tears of mourning! It is as though nature itself were weeping! And well it might, for there is death abroad this night!”

Over the course of 23 pages, fans got a tale in which the Joker revisits five of his former thugs, all of whom had betrayed him, attempting to murder each one of them while Batman races to stop him. Batsy is unsuccessful with the first four but just barely manages to save the fifth. All the while, the killings become more elaborate and gruesome. At one point, a notable Joker trope is introduced: He has the chance to kill Batman but chooses not to because the death wouldn’t be grand enough to befit the hero, whom he has a twisted affection for. In the final set piece, Joker imagines an elaborate deathtrap for a thug in a wheelchair, whereby he’ll be pushed into a tank with a ravenous shark. Batman and Joker strike a deal before the thug is killed; Batman will take the thug’s place. But Joker welches on the deal and pushes them both into the tank.

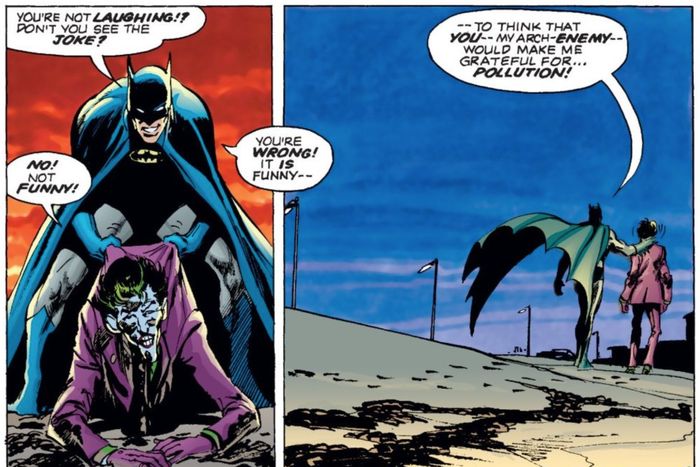

The climax is, paradoxically enough, the kind of goofy thing that might happen in the ’60s TV show: an underwater Batman wildly swinging a wheelchair at the wall of a giant aquarium in order to shatter it and escape. He’s successful and manages to catch up to the fleeing Joker when the latter trips and falls on an oil spill that he’d created as part of his murder plot, after which Batsy and Joker partake in some concluding banter. “You’re not laughing!? Don’t you see the joke?” Batman asks. “No! Not funny!” is Joker’s reply. Batman rebuts him: “You’re wrong! It is funny — to think that you — my arch-enemy — would make me grateful for … pollution!” (I’ll admit that I don’t really find it funny, either, so the Joker gets a point from me.)

That key word, “arch-enemy,” summed up nicely what the comic had achieved: It set up the Joker as a fearsome archetype of supreme importance in Batman lore for generations to come. Without Batman #251, we likely wouldn’t have had the Joker starring in such films as the Tim Burton–directed Batman, the aforementioned The Dark Knight, or Todd Phillips’s brutal new Joaquin Phoenix star vehicle — the latter of which is already being billed as the character’s apotheosis. The comic most often mentioned as source material for Joker is Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Batman: The Killing Joke, which posited a possible origin story for the Clown Prince of Crime. But as titanic as that 1988 story is, it likely wouldn’t have been possible if O’Neil and Adams hadn’t suggested a brutal interiority and chaotic instability for the character 15 years earlier.

The character has evolved greatly since 1973, but his fundamental status in the canon hasn’t changed. Adams saw the new film and is confident and more than a little proud that the ideas from his and O’Neil’s 46-year-old comic made it to the bad guy’s biggest moment yet. As he puts it, “I think that the result of that egg that Denny and I laid came out to be a really wonderful chicken.” Sounds about right for a guy who’s into jokes.