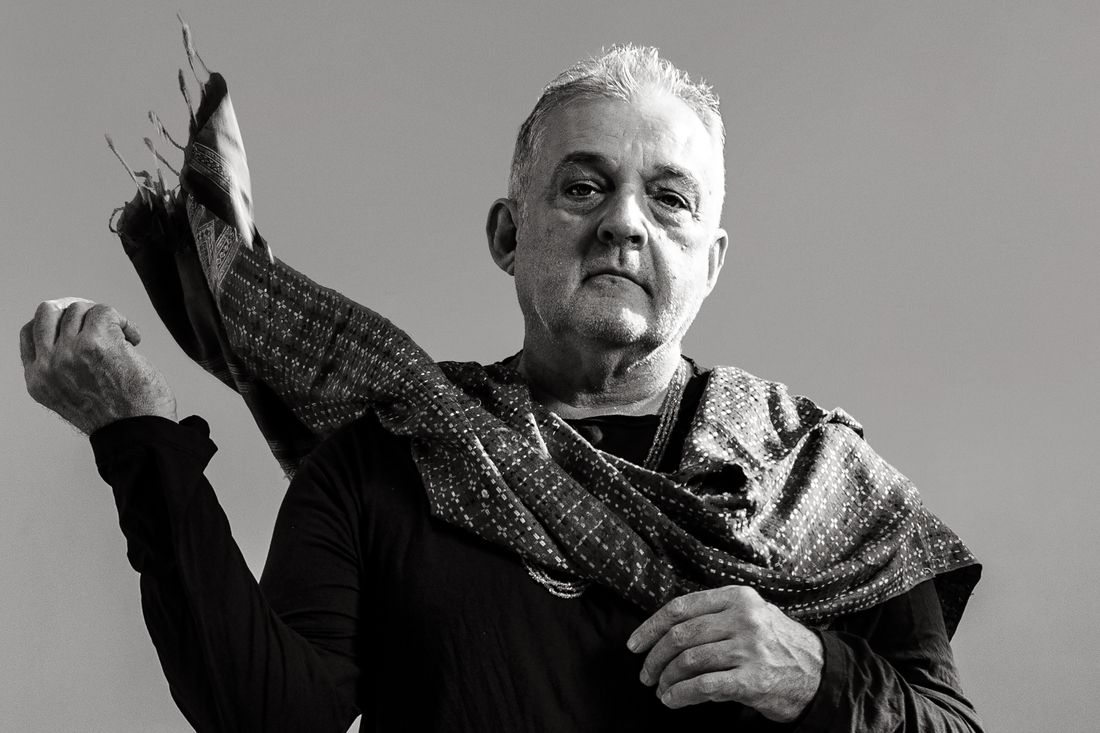

You cant write a big article about my office, says Mark Morris, arching an eyebrow. From somewhere in his disorganized desk, he retrieves what appears to be a miniature revolver, he pulls the trigger, and a small flame leaps from the barrel, along with  a tiny penis. Thats crazy, he says of the naughty novelty. I dont know why it would be both of those things. He lights the end of an incense stick and wafts it gently over his desk as if exorcising the malignant spirit brought forth by my temerity in asking why his office is furnished with a bathtub  a silly question, clearly: I fill the bathtub with water, I take off all my clothes, and I get in it. He stretches his bare feet wide under his desk and then directs my attention to the line of trophies on the shelf behind him. There are at least 15, the kind schoolkids earn for track-and-field events. I didnt win any of them, he says. I found them in the disposal room of my apartment building and figured someones teenage son died. His eyes sparkle with mirth. Or he went to college, he says. Then, because he cant help it: College or heaven.

The Mark Morris Dance Center in Fort Greene is not only the headquarters and factory for his renowned eponymous dance company but also a place for the rest of us to learn hip-hop, belly dancing, or salsa; it even offers movement classes for people with ParkinsonÔÇÖs. Morris truly believes dance is for everyone, and he built the building with that idea in mind. He even grudgingly approves of Dancing With the Stars. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm all for the way-too-wince-producing-but-fascinating dance thatÔÇÖs on television,ÔÇØ he says. Even Sean Spicer? ÔÇ£Hooray for him!ÔÇØ

Morris has now written a memoir, Out Loud, which is fragrant with his spiky humor. Early on, he recounts how, when he was 9, his mother took him to the Seattle Opera House to see the great flamenco dancer Jos├® Greco ÔÇö ÔÇ£with a big nose and a big basketÔÇØ ÔÇö and it set him fervidly on this path. (Vernacular dance styles continue to animate his work.) The book gives fans a backstage pass to the stories behind his greatest hits, like The Hard Nut, his retelling of The Nutcracker, in which, instead of the dull parlor dances of the 19th century, we get the hokeypokey, drunken boors, and randy teens, plus a set by the graphic artist Charles Burns. Morris had always loved TchaikovskyÔÇÖs music ÔÇö as a 14-year-old, he had danced to it in costume as a mushroom ÔÇö but hated the ballet itself. This was his fix.

ThereÔÇÖs lots of gossip and score-settling in Out Loud and a good deal of his friend Mikhail Baryshnikov. And donÔÇÖt expect him to explain himself. When interviewers ask, ÔÇ£What do you want the audience to get?ÔÇØ he responds, ÔÇ£Home safely.ÔÇØ Years ago, while working as resident choreographer at the national opera of Belgium, he told a journalist whoÔÇÖd asked about his dance philosophy, ÔÇ£I make it up, and you watch it. End of philosophy.ÔÇØ (This kind of tart response went down less well with the Belgians than it did back home.)

Then there was that time in 1984 when he was offended by what seemed to be a graphic depiction of sexual violence while watching a performance of Twyla TharpÔÇÖs Nine Sinatra Songs. He yelled, ÔÇ£No more rape!ÔÇØ and stormed out. It was the heckle heard round the (dance) world. ÔÇ£I still feel that way about the piece,ÔÇØ Morris says. ÔÇ£And it doesnÔÇÖt mean you canÔÇÖt have a rape in a show if you need it, but it should be horrifying if youÔÇÖre going to do it, not [presented] as a joke. I just found it gratuitous and awful.ÔÇØ For a while, Morris stopped getting invited to the American Dance Festival. HeÔÇÖs more diplomatic these days, but perhaps only a little. ÔÇ£I saw a piece by Paul Taylor a couple seasons before he died,ÔÇØ he recalls. ÔÇ£It was, like, five men and a woman forcibly have sex with a young woman.ÔÇØ He winces in distaste and mimes an audience applauding. ÔÇ£I was agape.ÔÇØ

Morris thinks contemporary ballet is sliding backward. He is particularly offended by the way it reduces women in the pas de deux ÔÇö ÔÇ£like harmless shampoo commercials, hair in the breeze, not a care in the world, but thereÔÇÖs a man towing you around like a mannequin.ÔÇØ He scowls. ÔÇ£And the audience is still predominantly majority culture and a lot of little girls dragged there with their pink outfits on. I know a lot of little girls who love pink, but I donÔÇÖt love that theyÔÇÖre handed a pink outfit at birth.ÔÇØ

Morris moved to New York in 1976 and says the best decade for sex was the ÔÇÖ70s, at least for those who survived. He didnÔÇÖt expect to live, because which gay man did in 1984? And yet here he is.

Partway through the book, he apologizes for its lack of sex, but he has already dispatched, or been dispatched by, several boyfriends at that point in the narration. Thereafter, he is defiantly single. ThereÔÇÖs a funny story of dialing a phone-sex chat line, before there were apps for that, and arranging to meet the man on the other end only to realize it is his friend Isaac Mizrahi. (ÔÇ£I guess when youÔÇÖre horny, nothing stops you,ÔÇØ Mizrahi says.) The two had met when Anna Wintour tried to set them up. Mizrahi was working on costumes for Morris at the time and walked into class the next morning to find that everyone had already heard the story.

ÔÇ£I have sex very, very infrequently, partly because IÔÇÖm not very interested,ÔÇØ Morris says. ÔÇ£You get to an age or a shape or a something cultural where youÔÇÖre not being cruised all the time, where itÔÇÖs like you donÔÇÖt automatically turn around and look to see if someoneÔÇÖs looking at you.ÔÇØ Besides, he is a good boyfriend to himself. ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt eat out of the refrigerator,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£I set the table and have a candle and a linen napkin and a fork.ÔÇØ His idea of a good night in is whipping up some Indian food and watching Jeopardy!

The Tharp moment helped Morris get cast as the resident bad boy of dance, though today he might be f├¬ted as a MeÔÇ»Too hero for his callout. In that regard, as in others, Morris was a pioneer, dispensing with outdated ideas about body types and age that many dance companies continue to grapple with. ÔÇ£Not only do I fully applaud the new activism, I also feel part of it,ÔÇØ he writes in the book. ÔÇ£But having to monitor everything one says and does is a little eggshell-y for me.ÔÇØ He also knows his perfectionism can veer into bullying. When an anonymous suggestion box was set up at the Dance Center for people to submit their grievances, it filled up quickly. ÔÇ£It was distressing,ÔÇØ he admits.

When he steps into the studio to start on a new piece, he almost never knows the end point. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a puzzle, and I pull the rug out from under them as well as from under me,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖll say, ÔÇÿYou do that, you do this. Reverse it. Go the other direction. Lie on your face and do it. Now slow motion. Now with a partner.ÔÇÖÔÇàÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a process. Even today, he confesses, ÔÇ£I feel like a fake a little bit, an unprepared charlatan.ÔÇØ He says he is always waiting to get caught out, even when thereÔÇÖs nothing to be caught out for. ÔÇ£Going through Customs, I assume IÔÇÖm smuggling heroin.ÔÇØ

But whether despite or because of this, work keeps tumbling out. Recently, he was in Enniskillen in Northern Ireland, where he directed three short works by Samuel Beckett. The brevity of the pieces, ranging from three to 15 minutes, felt like a complement to what Morris has already been doing in his work ÔÇö decluttering and stripping his sensibility back to the kernel of what he wants to express. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve been essentializing, as I would put it,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£When youÔÇÖre young and thrilled, and thrilling yourself, and feel deeper than anyone ever has, you put everything you can possibly think of into everything you do ÔÇö the first dances you do, the first piece of music, the first book. Everything is overstuffed and hard to read.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖs never long-winded,ÔÇØ Mizrahi says. ÔÇ£HeÔÇÖs not a fancy guy. Mark loves to do laundry.ÔÇØ Morris has created over 150 works since founding his company in 1980, and heÔÇÖs now busy on new ones that he has decided will premiere only after his death. At times, his memoir reads a little like a valediction; he seems to spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about the ends of things and what heÔÇÖll leave behind. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm leaving dances to my company, to the dancers of the future,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs like IÔÇÖm emptying my pockets before I put my clothes in the washer.ÔÇØ He pauses on the thought, as if turning it over in his mind. He says, ÔÇ£Throwing your clothes in the wash ÔÇö thatÔÇÖs a beautiful analogy about dying.ÔÇØ

Out Loud will be published on October 22.

*This article appears in the October 14, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!