Between Senegal and the Canary Islands stretch almost 1,000 miles of ocean. Cruise ships cut through the waves like knives. They make the journey in 11 days, and their passengers, who pay upward of $4,000 for a ticket, disembark unscathed. But luxury tourism almost always involves a contortion of optics. Since the mid-1990s, thousands of people along Senegal’s coast, most of them young and poor, have boarded smaller boats, typically used for fishing, in hopes of reaching Europe. The Canary Islands — which sit about halfway between Senegal and Europe and are an archipelago belonging to Spain, making them part of the EU — are often their first stop. Along the way, the waves can appear as big as mountains, and the boats, made from wood and rusted nails, act as fragile as flesh. An unknown but staggering number of migrants have drowned, and their bodies populate the ocean as if it were a mass grave.

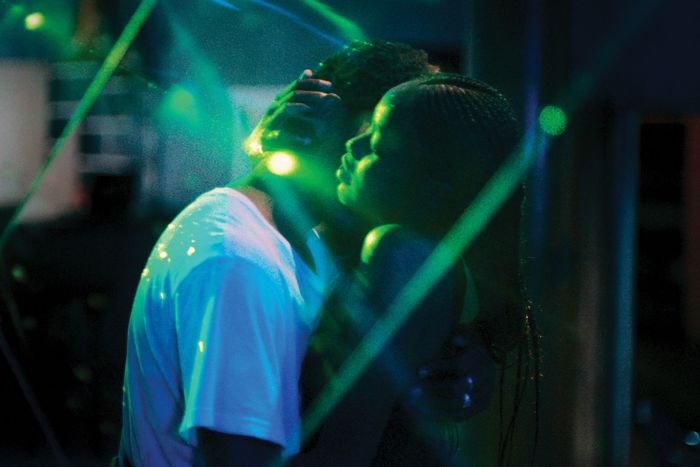

In the beginning scenes of Atlantics, the much-lauded debut feature film from French-Senegalese director Mati Diop and the winner of this year’s Cannes Grand Prix, a group of young men depart from the suburbs of Dakar in search of work in Spain. Their exit is swift and carried out in secret — their mothers, sisters, and lovers discover the loss only after they’ve gathered at a local nightclub and pass the news around like a handkerchief. The club might as well be a funeral home; it’s as if the boys were dead already. In life, they were construction workers, and their disappearance forces the architecture of the city to take on new, illusory shapes. A half-built skyscraper, initially the glimmering totem of economic promise, becomes a monument of suffering, and the shoreline, once a locus of fascination, starts to feel like a choke hold.

Ada, the film’s 17-year-old lead, begins to sense the spectral presence of her missing lover, Souleiman, in places where he doesn’t belong: in her new iPhone, purchased by her fiancé, whom she despises, and in the body of a cop who claims to be seeking justice but would rather see her in jail. In Atlantics, loved ones, geographies, nations, and institutions make false promises, and the thwarted desires of Diop’s characters provide the central drama of the film, which will be distributed by Netflix later this month. In October, it was submitted to represent Senegal in the competition for Best International Feature Film at the 2020 Oscars. If nominated, which seems likely, it will be the first Senegalese film to vie for the award. If it wins, it will be one of only four African films to have clinched the prize.

“When you talk about death in a movie,” Diop tells me as we pace the length of Harlem’s Morningside Park, “it’s also to reevaluate the importance of life.” Ambulance sirens drone in the distance, occasionally spliced with the shrieks of a jackhammer. We were supposed to meet for lunch at a restaurant on the stretch of 116th Street nicknamed “Little Senegal,” but when we arrived, the place appeared to be deserted. The door was open but the lights were off, and without the approval of a host or waiter, it seemed foolish to assume our roles as patrons. We decided to go for a walk.

Diop, I quickly discovered, can conscript nearly anyone into a collaborative mode of speech. She gestures profusely and speaks in long, swollen sentences, only to pause before uttering her final word. During her introduction for a New York Film Festival screening of two films by her uncle, the legendary Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty, audience members finished at least two of her sentences. Diop invites the participation. During our conversation, we speak in English, though she sometimes turns to an interpreter who translates her more thorny sentiments from French. When describing the “borders” and “limits” of the popular discourse around cultural appropriation, for example, Diop speaks in a combination of both languages. “It can get into really basic, even primitive, communalism,” she says. “These questions are very complex subjects, and I think they’re too often reduced to — ” When neither of us offers a conclusion, she switches from argument to appeal. “Help me!,” she squeals, laughing at herself. “But we don’t know what you’re going to say!,” exclaims the interpreter. After a beat, Diop demurs: “It’s all about point of view.”

Filming Atlantics was also a joint effort. “I guess I need the people who act in the film to know more about the characters than I do,” Diop tells me. “I need them to have experienced it, so when they act, it’s about them.” The cast is composed of first-time actors, and she found most of them while they were going about their daily lives. She says, “I was looking for people who have a social background that makes them connected with the reality of the characters.” Ibrahima Traoré, who plays Souleiman, is a construction worker by trade. Ada, who in the film is forced into an arranged marriage and gains greater control over her fate only when visited by what appears to be the ghost of Souleiman, is played by Mame Bineta Sane. When Diop found her standing outside her family’s home on the outskirts of Dakar, Sane had quit formal schooling and was planning to marry. The Kuwaiti electronic musician Fatima Al Qadiri, who composed the film’s score, describes Diop’s directorial style in mystical terms. “There’s a lot of providence in Atlantics,” she tells me. (Al Qadiri herself almost drowned when she was 10 and is terrified of the sea.) “Mati is a bit of a witch.”

Mati Diop was born in 1982 in Paris. Her mother is French and white, and her father, Wasis Diop, is a Senegalese jazz musician who moved to France in the 1970s. When she was 26, she made her acting debut as the daughter of a father played by Alex Descas in Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum. The film follows Diop’s character as she matures out of the apartment where the pair has shared meals, friends, and unexpected grief. Her performance is subtle, and the familial intimacy between her and Descas is as quiet and obvious as a hug. Nevertheless, France, she tells me, “was not ready” for 35 Shots of Rum. French viewers “didn’t understand how a film with a black man could not have as its subject his blackness.”

Because coming-of-age films are saturated with images of white suburban angst, black actors are rarely depicted in the tenderness of adolescence. “In my childhood, my own identity complexities were experienced and articulated in a lonely way,” Diop tells me. Until now, she explains, French people have never referred to her as a “black actress” or “black director,” a symptom of the country’s purportedly capacious brand of nationalism but also its vexed relationship with the legacies of colonialism. In May, she was the subject of a short profile in The Hollywood Reporter, in which she was cited as saying, “I don’t think of myself as white or as black. I just think about me as me.” The quote was an error of translation, she says. “I was like, Is it really gonna be like that? People are gonna ask me if I’m black or not black?” I suggest the mix-up may have been a side effect of the American media’s obsession with the figure of the “tragic mulatto,” an archetypal mixed-race person unable to escape his or her own feelings of alienation, and I ask if a French equivalent exists. “I don’t know,” Diop says, laughing. “But I understand.”

When she began making films in Senegal at the age of 26, Diop encountered an apathetic audience. “Nobody around me in Paris was really interested in Africa, even filmmakers. I felt quite marginalized at the time — a bit isolated, actually.” Since then, she has directed a handful of short films that dwell on the strange, often alienating cusp of adulthood. Two are set in Dakar. Her 2009 short, also called Atlantics, shares a premise with the new feature: A young man, having returned from a perilous attempt to migrate across the Atlantic in a canoe, describes the effort to his friends as they sit by a bonfire. Soon, cinéma-vérité bleeds into fantasy. A fever, we’re told, descends upon the city and strikes the man nightly. Mille Soleils, released in 2013, harnesses myth in a similar fashion. It’s an homage to her late uncle’s 1973 feature Touki Bouki, which follows a pair of young lovers as they scheme their way into two ferry tickets to France. (Last year, while promoting their On the Run II world tour, Jay-Z and Beyoncé styled themselves in the image of the leading couple in publicity images, touting the film’s iconic horn-clad motorcycle. “It is depressing and fascinating at the same time,” Diop said then. “The unbearable lightness of the mainstream.”) Mambéty died of lung cancer when Diop was 16, and the interruption of his career enabled the burgeoning of hers. Mille Soleils reunites Touki Bouki’s lead actors 40 years later, rewriting their divergent fates.

From the documentary impulses of Diop’s previous works, Atlantics spins a fantasy of retribution. The lost boys come back as ghosts to demand their stolen wages, and Souleiman, who feels Ada’s tears in the tide that kills him, reappears to impose life in his lover, who continues on without him. The resulting choreography is something of a mesmerizing bait and switch. What initially appears to be a personal drama morphs into a political phantasmagoria, only to return to the quotidian experience of growing up.

Diop originally crafted Atlantics as a survival film, stripping the genre of its typical, action-movie-style accoutrements and opting for more intimate exchanges: arguments between mother and daughter, favors passed between friends, sex. “The violence of a certain capitalist economy makes a lot of life fragile, vulnerable, and empty of meaning,” Diop tells me. “The film is about the beauty and innocence of love between two 20-year-olds, which is ruined and cut down by economic issues, with Souleiman having to leave by boat for Spain because he’s unpaid and Ada having to marry because of social pressure.”

At the same time, Diop wanted to write “a fantasy film about the loss of this generation of boys.” For the tens of thousands of real-life migrants who have drowned in the Atlantic, there exists no official memorial. But in Atlantics, the ghosts of the missing boys demand to be remembered by the skyscraper that overshadows the city. Its image appears in advertisements that plague the film’s scenes like omens. The name given to it by the developers — Muejaza — is Arabic for “miracle.”

Diop is the first black woman filmmaker to compete at Cannes, a designation more often cited as a testament to her talent than as a belated recognition of exclusion. As we descend a hill toward the southern edge of the park, I ask to what extent the film’s success has forced her to navigate the constricting narratives around contemporary African life. “As a mixed girl, born in Paris but also coming from Senegal, I’m very aware of how Africa was dispossessed of her own story, image, representation.” (As she speaks, I feel her tug my shoulder in an attempt to divert my path. When I look down, I realize she has saved me from stepping on a petrified mouse, so alarmingly pristine as to appear like the discarded work of a taxidermist.) “In my childhood and adolescence, I took time to understand the extent to which Africa is denigrated in a way that is both official and nonofficial,” she continues. “There’s a permanent tension between how I think Africa is and should be represented and how I know it’s seen from the exterior. In my filmmaking and in the way that my films are engaged and committed in Africa — I don’t know that reparations is the right word, but there’s nearly a way of reconstructing and repairing a certain image of Africa.”

In the ten years between the releases of Atlantics the short and Atlantics the feature, Diop’s sense of isolation has given way to something that approximates celebrity. Her filmmaking, once marginalized, will now be distributed by the world’s largest streaming platform, a change she attributes to the burgeoning desires of black spectators. “I think that a lot of people like us — mixed, or crossed by different cultures, or partly African — have really felt the need to reconnect with our origins,” she says. “While I myself was doing that reconnection, I felt that many black people around the world were doing the same. And voilà — I feel that there is a certain audience for Atlantics that didn’t exist ten years ago.” Since the film’s debut, Diop has received a number of messages, mostly from people younger than she is, telling her they’ve been waiting for a film like this. “And I know exactly what they’re talking about,” she says. “The lack they describe is one of the stories of my life.”

When I ask Diop if the skeptics of years past still haunt the reception of her work, she tells me that Atlantics has found a reconciliation. “There isn’t really an entry for people to misunderstand. To make the choice to shoot a film in Dakar, in Wolof, about these people, these women, and this situation — I shouldn’t have to justify myself. The point of view is quite clear, and so people don’t really have space to —” Here she dwells in a characteristic pause. The translator offers a few suggestions: “Misinterpret me?,” “Give me trouble?” Diop smiles coyly. “To mess with me,” she says with a wink.

*A version of this article appears in the November 11, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!