The second installment of a three-part recap of the 2010s. Read part one, “Keep On Dancin’ Till the World Ends,” here. Read more about this series here.

Part Two: 2013-2016

On January 21, 2013, at the steps of the Capitol Building, Barack Obama was publicly sworn in for his second presidential term. His reelection had seen him win slightly fewer states than in his first go-around, a sign that the bloom was off the hope-and-change rose; as the New York Times noted on the occasion, the “expectations that loomed so large [with his] taking the office in 2009 … have long since faded into a starker sense of the limits of his presidency.” Even so, the nation could still spectacle, and that day the force of Obama’s vision was brought to life through Beyoncé’s rousing rendition of the national anthem, which saw the singer dramatically rip off her earpiece at a climactic moment, flying solo on the final high notes. Fittingly for the era it kicked off, the moment soon bred its own micro-controversy: Had Beyoncé really sung live, or was she lip-syncing? As with much in the subsequent four years, the truth was slightly underwhelming compared to the massive amount of coverage it engendered. She had actually been singing along to a prerecorded track, though whether you saw this as vindication largely depended on your preexisting feelings about the singer.

This was the story of Obama’s second term, in which optimism gradually gave way to doubt and recrimination. Though Republicans had failed in their primary goal of making Obama a single-term president, they had succeeded in their secondary one, stripping the president of his dreams of ushering in an era of bipartisan compromise. But the energies and expectations aroused by Obama’s presidency had to go somewhere. So they entered the realm of pop culture, where politics became inseparable from cultural discourse. These years were marked by rapid evolutions in acceptable language and behavior; constant debates over diversity and inclusion; frustration on the left that the world was not changing fast enough, and misgivings elsewhere that it was changing at all. In retrospect, this era would attain a faint Belle Époque glow, but it did not feel that way at the time.

The gap between the dream embodied by the nation’s first black president and the lived reality of its black citizens was felt acutely in these years. In the winter of 2012, neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman had shot and killed a black teenager named Trayvon Martin; Zimmerman’s acquittal in the summer of 2013 spurred the creation of the Black Lives Matter movement, which in the years to come would focus national attention on similar killings of unarmed black Americans, often by the police. Public intellectuals like Michelle Alexander and Ta’Nehisi Coates made painfully tangible concepts like mass incarceration and the U.S. government’s contribution to the racial wealth gap, while artists like Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar released music in which their pride, joy, and sorrow were inseparable from their blackness. Social media also sped up the process of cultural borrowing that had been going on for centuries. A teenage girl in Chicago could make up a nonsense word one day and see it become a nationwide catchphrase the next. The loose collective known as Black Twitter unofficially set the discussion topics for the mainstream media, though few of them were paid for the gig. All of this in turn made white Americans increasingly cognisant of their own race — with disparate results. White liberals, who had previously preached a polite color blindness, began en masse to recognize the wide scope of racism in America, while conservatives resented being constantly reminded of their white privilege.

In 2014, a series of disparate events galvanized awareness of how far the nation was from true gender equality. In May, self-described “incel” Elliot Rodger killed six UC Santa Barbara students as part of a misogynistic revenge fantasy. Over Labor Day weekend, hackers leaked a cache of private nude photos they’d obtained from the iCloud accounts of various female celebrities. And throughout the fall, hordes of mostly young men in the Gamergate movement harassed prominent women online under the nebulous guise of “ethics in video game journalism.” Together, Rodger’s massacre and Gamergate suggested respectively the depth and breadth of the misogyny lurking beneath the surface of polite society, while the iCloud hack indicated that no amount of wealth or status could insulate women from becoming targets. Though in an earlier era the leak might have been widely celebrated, now it was generally recognized as the serious invasion of privacy that it was. The Santa Barbara shooting spurred its own social media moment: #YesAllWomen, which highlighted instances of everyday sexism, and set the table for the revelations that would come three years later. This era saw stars like Taylor Swift and Emma Watson embrace new roles as what Roxane Gay dubbed “brand ambassadors” for feminism; in this as in many endeavors, they were outdone by Beyoncé, who not only emblazoned the word on her stage backdrops, but also famously included on her self-titled album a spoken-word excerpt from the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie defining the concept.

In other matters of gender and sexuality, the legalization of gay marriage, the rare unqualified political victory of the Obama years, marked the arrival of LGBTQ culture as a powerful commercial force: Queer slang became widely appropriated, and queens from RuPaul’s Drag Race began showing up in Starbucks ads. Even anilingus got a moment in the sun, with dire results for the nation’s plumbing systems. But it was the previously undefended flank of trans rights that soon became the new cultural battleground: If society could accept those who loved the same gender, why couldn’t it then also accept those who identified as a different gender from the one they were assigned? Streaming series such as Orange Is the New Black and Transparent featured relatable trans characters, as did the reality show Keeping Up With the Kardashians, where the public transition of Caitlyn Jenner was a major story line. (How swiftly standards in this arena evolved could be seen in the case of Transparent creator Jill Soloway, who went from casting a cis actor as a trans character to declaring the practice “unacceptable” in the space of three years.) Trans acceptance went hand in hand with increased recognition of other identities, from asexuality to nonbinary. The precarity of certain long-held ideas around gender deeply troubled traditionalists, who responded by creating a public ritual meant to reassert the primacy of biological sex. These were called gender-reveal parties.

The heightened awareness of social issues during this era created a new kind of culture war, fought over issues of language and etiquette. Constituencies that had previously lacked a media apparatus suddenly had space on social media to air their concerns, though progressive norms would outpace public opinion in some areas, as shown by the later controversy over the term Latinx. Unlike previous culture wars, this one was primarily an intra-left affair, and its combatants would become the public face of liberalism in their era.

With this war came fresh battle lines: To be on the right side of history was to be woke, a word taken from black intellectuals and artists; to be on the wrong side was to be problematic, a term whose definitional murkiness and shades of passive aggression hinted at its origins in academia. It was one of a long list of expressions to jump out of the academy in the Obama years, alongside white privilege, appropriation, and intersectionality; slangier buzzwords, like mansplaining and slut-shaming, emerged out of the feminist blogosphere.

All of these concepts got messier and less specific once they entered general use. In a sign of how easily the desire to stand against oppression could be subsumed into an elaborate social competition, woke evolved from a straightforward compliment to a term of derision for those who seemed to be trying too hard. Wokeness-based critiques often proved extraordinarily difficult to litigate in public, as no one could ever quite agree which were sincere attempts to improve the world, and which were merely bids to boost one’s own personal brand. (In the parlance of the times — which is to say, a Mean Girls reference — calling someone else fat didn’t make you skinny, but calling someone else problematic did make you woke.) If you generally believed in progressive values but objected to specific statements, you called them performative; if you were opposed to the entire process, you called it virtue-signaling.

In the media, where prerecession budgets were simply not coming back, stories around these issues were usually cheap and quick to produce, and drove engagement like nothing else: Those who were outraged by a given offense were driven to like and share, and so, too, did those who were outraged by the outrage. Pop culture was an especially fruitful arena for discussion and many celebrities found themselves used as signposts for new sociological terms. The question of how to be an ally was embodied by the rapper Macklemore, a straight white man operating in a traditionally black art form, who’d broken out with a song about gay rights. Lena Dunham, Tina Fey, and Taylor Swift spoke cogently about issues that affected them, but were frequently tone-deaf on everyone else’s — together they personified white feminism. The shameless way Iggy Azalea and Miley Cyrus treated blackness as a costume was textbook cultural appropriation. Through the telephone-game nature of the internet, progressives convinced themselves that Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” was promoting rape culture. In what became the Avengers for problematic musicians, the latter duo teamed up at the 2013 VMAs, where Cyrus twerked on Thicke’s crotch — the decade’s signature moment of pop-culture provocation.

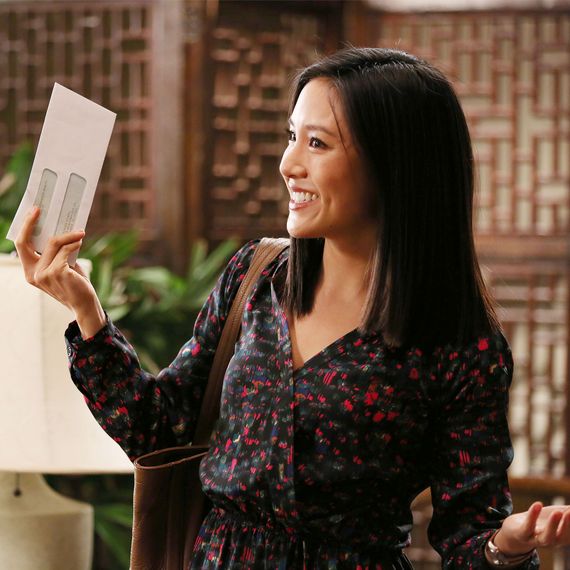

Despite how it felt to some, not everything was problematic. The era’s push for greater pop-cultural representation did bear real fruit. Fresh Off the Boat, Dr. Ken, and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend told Asian-American stories on network television for the first time since the ’90s, while Jane the Virgin was the closest an English-language channel got to broadcasting a telenovela. The #OscarsSoWhite controversy sparked the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to dramatically reshape its membership. The trend of auteur comedy kicked off by Louie paved the way for diverse, idiosyncratic visions like Atlanta and Master of None. You may notice that most of these took place on television, often on streaming: As the movie industry was dominated by tentpole franchises starring blond men named Chris, the influx of nonwhite and female creatives in TV was the most exciting industry development of the period.

The spirit of the times made personal virtue an ever-more-important quality. A new breed of male celebrity, the “woke bae,” emerged, as did a new class of sitcom that offered viewers lessons in moral instruction. Louie, Master of None, and You’re the Worst explored how to live an ethical life in the fallen world of the 21st-century entertainment business; BoJack Horseman did the same, but with an anthropomorphic horse-man. Debuting at the tail end of this era was The Good Place, which made the subtext text by featuring explicit lectures in moral philosophy.

Those ostensible comedies were often mocked by actual comedians for their darkness. Other popular culture from this time was darker still — and not just visually. The Netflix series Jessica Jones and the unexpected Best Picture nominee Mad Max: Fury Road each brought an unflinching treatment of sexual violence to highly stylized fantasy worlds. (Both were often contrasted to Game of Thrones, which around this period was gaining a reputation for mishandling rape scenes.) Warner Bros.’ attempt to create a cinematic universe out of its DC Comics properties was marred by its decision to lean into the contrast with the ever-sunny MCU: The resulting trio of Man of Steel, Batman v Superman, and Suicide Squad was a parade of ever-more-ludicrous grimness.

More effective was the HBO miniseries True Detective, a southern gothic crime tale with an added dose of Lovecraftian mythology, which infused an already dour genre with a new kind of horror. (The second season was less supernatural but even more spiritually bleak, a tonal brew that was incapable of conjuring the same magic.) True D’s philosopher-cop Rust Cohle turned out to be a preview of the characters that would enthrall audiences on the rightward side of the political spectrum. His adage, “The world needs bad men; we keep the other bad men from the door,” could have been the motto for red-state heroes of the era like the Punisher and Chris Kyle of American Sniper, Christian soldiers who burdened their souls with unspeakable acts committed on behalf of an ungrateful populace. For conservative viewers confronted with a culture increasingly skeptical of state violence, this was vital consolation.

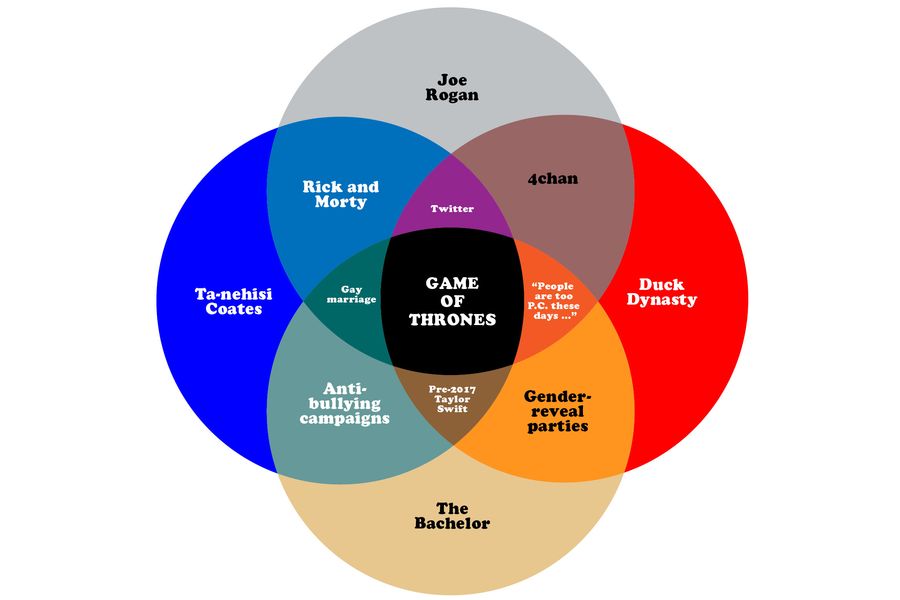

Some souls attempted to stand outside the red-blue divide. These years saw the development of what blogger Scott Alexander dubbed gray culture, “typified by libertarian political beliefs, Dawkins-style atheism … eating paleo, drinking Soylent, calling in rides on Uber,” and more. (To that list I would also add CrossFit, Joe Rogan’s podcast, enthusiasm for tech moguls like Elon Musk, and being upset by the idea of female Ghostbusters.) The counterpoint to gray culture was what we might as well call beige culture, best defined as an attempt to remove oneself from the messiness of politics altogether. Artifacts from beige culture included the Bachelor franchise, HGTV, Christmas movies, everything on your Instagram Discover page, The Great British Bake Off, People stories about objectively beautiful celebrities clapping back at body-shamers, the practice of calling dogs “doggos,” and avocado toast. (Though beige culture’s spiritual home was California, many of its hallmarks originated in Australia.) Beige culture was also closely related to the concept of the basic bitch, a common self-deprecating term in these years.

America’s Four Cultures:

Put broadly, gray was about efficiency; beige was about comfort. Despite all their differences, gray and beige tribes turned out to share one thing in common: a penchant for Instagramming photos of low-carb meals. The area where they came together was called the wellness movement, a set of aspirational goals centered around good health (often a code word for physical attractiveness, paramount in an image culture), mindfulness, and conscientious consumption. Its uniform was athleisurewear, a type of clothing meant to advertise that its wearer was about to commence, or had just finished, working out, and which by the end of this era was approaching $100 billion in sales. This clothing signified above all else effort, so it made a strange amount of sense when the trendiest fashionistas in this period began embracing an effortless, utilitarian look known as normcore.

The world was changing color, too. Harsh metallics were out; a new, softer palette was in. A variety of factors contributed to the shift. The Arri Alexa camera, introduced in 2010, recorded in a low-contrast color space that soon became the default aesthetic for music videos and commercials. The wellness movement popularized an entire spectrum of pastel-colored food and drink: the frothy lime green of avocados, matcha lattes, and kale smoothies; the subdued gold of turmeric tonics. But the period’s defining shade would originate in the world of luxury fashion. In 2012, Piaget unveiled a rose ring made out of 18-karat pink gold. And then I think it was Phoebe Philo and Jonathan Saunders, wasn’t it, who both showed muted pink coats at Fashion Week the following year. A similar shade of pink showed up in makeup packaging, interior design, book covers, and iPhones soon after. Fashion called it “dawn pink,” tech and jewelers “rose gold,” Pantone “rose quartz.” But it proved so appealing to the younger generation that its most lasting sobriquet was simply “millennial pink.” This pink was not the bright neon of the ’90s but instead a desaturated salmon not far from actual beige. It signified femininity, but, you know, a new kind — a semiotics nebulous enough to be employed by period-panty manufacturers and Drake alike.

When did this era end?

In January 2015, a new Off Broadway musical debuted at the Public Theater. Hamilton was an immediate sensation: a musical biography of the first secretary of the Treasury, filled with frenetic raps, shout-outs to immigrants, and a cast as diverse as New York City itself. It transferred to Broadway six months later, and became the most successful new show of the decade after Book of Mormon. The project had debuted in embryonic form at the 2009 inauguration, and now seemed a crowning summation of Obama’s America — proof that the nation’s founding ideals could be reclaimed as symbols for the president’s coalition. It turned out to be their swan song.

At the height of Hamilton-mania, the same weekend the show’s cast performed at the Grammys, Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia died in his sleep. The 2014 midterms, known as the “election about nothing,” turned out to have been about something after all: Thanks in part to low turnout, Republicans recaptured the Senate, and now used their majority to block Obama from filling the seat. (In a culture built around public shaming, shamelessness was a superpower.) That single act raised the stakes of the upcoming presidential contest, eventually leading the Republican Party apparatus to reluctantly rally around the despised candidate who was at this very moment leading their primary contest, the figure who in his bigotry and mendacity would come to personify the end of the Obama era and the beginning of a terrible new age, and a man I have waited until the last possible moment to introduce — Donald Trump.

History is rarely kind enough to give us clear markers. In this case, it did: This era ended at 2:30 a.m. Eastern Time on November 9, 2016.

Stray Observations

• The realm of independent cinema was one aspect of culture to resist the desaturation trend. In 2013 the indie distributor A24 released its third film, Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers, with cinematography bathed in lurid neon. Over the rest of the decade, the company would define the shape of independent cinema, specializing in what Manohla Dargis dubbed the new American Expressionism, a string of ultrahip low-budget films often marked by intense bursts of saturated color.

• Not all forms of cultural borrowing in this era were met with opprobrium. In this period Drake in particular made a habit of gobbling up sounds from across the globe, culminating in his 2016 dancehall hit “One Dance,” which became the rapper’s first solo chart-topper. In another sign of the times, the song did not have a music video, an indication of the medium’s fading influence in the Spotify era.

• Audio streaming was the medium for another pivotal pop-culture event in the fall of 2014, as the miniseries Serial sparked a podcast boom that lasted the rest of the decade. It also demonstrated that the intense fan theorizing that had greeted series like Game of Thrones and True Detective need not be limited to fictional stories — and thus, a new true-crime craze was born.