The final installment of a three-part recap of the 2010s. Read part one, “Keep on Dancin’ Till the World Ends,” part two, “We’ve Come Too Far to Give Up Who We Are,” and read more about this series here.

Part Three: 2016–2019

In the years of his presidency, Donald Trump loomed like a colossus over American life. Merely describing him became a popular parlor game: Some said that his self-conception was that of “someone cleaning up at an endless televised awards show,” others that he resembled “the bad guy in a movie where the hero is a dog.” One account both his admirers and detractors could agree on was this: In a healthy society, he would not have become president. On the right, his victory was seen as cleansing retribution for the decadence of the Obama era. On the left, the election of a racist reality-TV host who had been caught on tape bragging about grabbing women’s genitals and who had received nearly 3 million fewer votes than his opponent was felt as a collective psychic trauma. In Broad City, a show that had embodied millennial wokeness, Trump’s name was bleeped out, like a 21st-century Voldemort.

Trump was the lens through which all else was viewed. In the early months of 2017 you could not watch an acceptance speech or read a movie review without encountering his name. Political pundits expended much effort trying to pinpoint the reason behind his surprise victory, but the culture industry relitigated the 2016 election in a different way. Every public competition became an opportunity to psychologically replay the race. Sometimes, as at the Moonlight versus La La Land Oscars, the good guys pulled off the last-minute victory. Others, such as the Super Bowl that pitted the Trump-adjacent New England Patriots against the Atlanta Falcons, went down in dispiritingly familiar fashion. There was a widespread sense that the world had been knocked off its axis.

The president’s governance encouraged this type of thinking. He had realized that politics was becoming like sports: For much of his base, his actual accomplishments were secondary to the fact that he made Democrats absolutely furious. Besides a large corporate tax cut, Trump’s policy decisions were mostly occasions to inflict pain on out-groups: limiting travel from predominantly Muslim countries; banning trans troops from the military; separating refugee children from their parents at the border — prompting Adam Serwer to coin the phrase “The cruelty is the point.” In opposition to his policies, protesters rushed airport terminals, and restaurant workers refused service for White House staffers. That was the fundamental bargain of the Trump age: The president and his allies would act with impunity, and in return 40 percent of the country would hate their guts.

As in the ’70s, the last time America had seen this much institutional distrust, pessimism and conspiracy ruled the day. In the wake of foreign meddling in the 2016 election, liberals wondered if Trump had been a Russian asset since the late ’80s, and obsessed over the existence of the mythical “pee tape.” Even conservatives who didn’t believe in underground pedophile rings run out of D.C. pizza joints found it easy to believe that every time Trump was accused of an abuse of power, the real crime had actually been committed by the Democrats first. The election also gave lie to the Obama-era belief that the arc of American history necessarily bent toward justice. The cultural touchstone of the age was Hulu’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, which presented a misogynist dystopia that affirmed progressive viewers’ worst suspicions about the way things were headed. Jordan Peele’s Get Out symbolized a waning faith in the 44th president’s strategy of appealing to white Americans’ better angels: The villains were nice white liberals who “would have voted for Obama a third time” if they could; they still sent the hero to the Sunken Place anyway.

With so much of society clearly rigged, scamming became a hallmark of the age. Scammers were not aspirational figures, exactly, but nor were they necessarily scorned. The strippers of Hustlers were celebrated, while figures like Anna Delvey and Elizabeth Holmes became objects of fascination. More outwardly villainous was Billy McFarland, the brains behind the disastrous Fyre Festival, but even there the sheer magnitude of his shamelessness held a certain charm. (It helped, too, that his hypebeast victims seemed almost fair prey.) The only scammers universally hated, it seemed, were the famous parents who had bribed their children into prestigious colleges — a scheme that didn’t tear down existing hierarchies, but reinforced them.

The election of a rank misogynist to the presidency could not help but have an effect on American women. Trump’s Inauguration Day was marked by a series of nationwide protests collectively dubbed the Women’s March — more than 600 events in all, with at least 3 million participants, marking the biggest turnout for a one-day protest in American history. The Women’s March kicked off an age of female anger, some of it with a mystical bent. “Women, especially, are communing around the witch figure and her ability to counter male dominance,” Doreen St. Félix noted around the time Wiccans came together on Facebook to place a binding hex on Trump.

In the fall of 2017, many once-dominant men discovered just how potent this anger could be. That October, the New York Times put on the record for the first time allegations of sexual assault by film mogul Harvey Weinstein that had been whispered about for years. The decade had previously seen similar revelations around Bill Cosby and Woody Allen, but the Weinstein story was the one that opened the gates for a flood of stories around other male celebrities: Louis C.K., Matt Lauer, Les Moonves, and countless more. (Though the specifics of each case were different, they were clearly linked; the catchall term sexual misconduct covered them all.) The rush of formerly silent women who came forward was dubbed the #MeToo movement, and its impact was felt in workplaces across the globe. It was possible to overstate the shift — for those who lacked the wealth and fame of the most prominent accusers, the consequences for speaking up were as often just as dispiriting as they had been before — but there was an unmistakable change in the temperature of gender relations. As one woman put it: Women had been scared of men for a long time; maybe men would be scared of women for a while now, too. Female anger also found its expression in the pop culture of the period, from Killing Eve to Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. There was a new willingness to celebrate women who weren’t afraid to step on toes: from puckish comedian Hannah Gadsby to the highly GIF-able mothers of Big Little Lies, among the few rich people who would be spared in the forthcoming revolution.

As with Eastern Europe after the fall of communism, the era’s social shift necessitated a debate about what was to be done with those whose conduct had been accepted or ignored under the old rules, but was clearly verboten with the new ones. Which misdeeds in the past were able to be brushed off as a product of their time, and which deserved retroactive punishment? Sometimes, the answer was easy: Cosby’s abuses were so abhorrent that no one complained when he was immediately pushed out of public life and later convicted of multiple sex crimes. But his was the rare case to enter the legal arena; most others were tried in the public sphere, where resolutions were much less clear. After Woody Allen’s daughter Dylan Farrow repeated her accusation that the director had molested her, the scandal did not initially interrupt Allen’s regular work schedule; only in the wake of #MeToo did he face a consequence, with Amazon canceling his four-picture deal. Louis C.K., who admitted to nonconsensually masturbating in front of female comedians, lost his TV deal, but began to perform again nine months later. Aziz Ansari, who as the world now knew had once attempted to coerce his young date into sex, kept a low profile for a year, then came back with a Netflix special that attempted to address the fallout. Each new case brought constant debate about whether the outcome was just, and what a just outcome would even look like.

This sense that the past was up for continual reinterpretation was felt throughout popular culture. The ’90s in particular came under the microscope: In 2016, a pair of critically acclaimed projects investigated the O.J. Simpson trial with fresh eyes, and the following year, former tabloid fixture Tonya Harding became the subject of an Oscar-winning biopic. Feminists reconsidered their earlier opinions of Monica Lewinsky, Lorena Bobbitt, and Andrea Dworkin. Even further back, critics debated how to feel about beloved rock stars who’d had sex with teenage girls, and social media saw yearly yuletide takedowns of the song “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” become a new Christmas tradition.

The Trump era was also a time of trauma. The psychological landscape of the aughts had been defined by fear of Islamic terrorism, but over the course of the 2010s the figure of the suicide bomber was replaced in the public imagination by a new bogeyman: the mass shooter. The aftermath of this violence quickly acquired its own scripted ritual: Democrats pleaded for more gun regulations; Republicans offered “thoughts and prayers.” If the shooter belonged to either side’s preferred category of villain — angry white men for the left, Muslims or immigrants for the right — hard-core partisans took a perverse satisfaction in the confirmation of their ideology. Then, nothing would change, and the world would move until it inevitably happened again.

Society, too, increasingly focused on trauma. The progressive lexicon was gradually colonized by the language of abuse and victimization; no one was simply lied to in these days, they were always gaslit. (The title of a buzzy nonfiction book of the era reminded readers Conflict Is Not Abuse.) There was a notion, put forth subtly in novels like A Little Life, and less subtly in M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, that trauma was a necessary precondition of a truly authentic life. A possibly more accurate depiction came in Fleabag, where traumatic loss just made you do terribly inappropriate things with a priest. Helping the depressed and anxious cope with such a world was the concept of self-care, which took the form not just of relaxing baths and yoga but also newfound interest in astrology and a boom in millennial plant ownership. Cutesy pop-culture totems did the trick as well, as demonstrated by the cult followings that arose near instantaneously around David S. Pumpkins and Baby Yoda.

The celebrity who best personified these times was a five-foot-tall former child star from Boca Raton. In the last half of the decade, the life of Ariana Grande was marred by frequent tragedy. In 2017, the singer’s Manchester concert was the site of a terrorist attack that left 23 dead. The following year, Grande’s ex-boyfriend, the rapper Mac Miller, died of an opioid overdose. Her resilience in the face of these trials was striking: Grande’s subsequent work was filled with resolve, self-love, and anti-anxiety tips — as well as a brief engagement to comedian Pete Davidson that enthralled the nation and helped popularize the concept of “big dick energy.” As Amanda Petrusich noted, Grande had absorbed the cardinal lesson of 2010s stardom: that “the fastest, truest route to communion with your fans is to reveal absolutely everything.”

In this era, new heroes and villains were being created every day. Taylor Swift, who had undergone oscillating fortunes on this front, released Reputation, a concept album about her experience of becoming widely despised in the summer of 2016. Some would say she had been a victim of cancel culture, a concept so ill-defined that many on the left argued it did not actually exist. The best way to put it was that being canceled meant becoming the subject of a broad online outcry, for a variety of possible offenses — sometimes committing serious crimes, sometimes expressing politically incorrect sentiments, sometimes wading into territory they shouldn’t, sometimes just kind of having an annoying vibe. As advocates of lustration had argued in the ’90s, many pointed out that no one was being thrown in jail, and few were even losing their jobs. Even so, there was undoubtedly a punitive mood in the air; in these years anyone who received a high-profile job could expect to see strangers digging through their old tweets as a matter of course. However, the most high-profile victim of cancelation was on the left: NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who was blackballed from the league for his National Anthem protests. And the right was equally capable of instrumentalizing outrage to target their ideological enemies. After Trump-loving comedian Roseanne Barr lost her sitcom for tweeting out a racial slur, conservatives took revenge by getting liberal director James Gunn fired from his superhero franchise over offensive jokes he’d made years before.

The debates over cancelation also played into a widening generational gap. The same gap would alter the era’s political landscape, as young voters who’d come of age amid the recession spent the decade moving further and further left. Trump’s election solidified the emerging consensus that the moderates had let the side down. For politically engaged millennials, socialism was not a dirty word, capitalism was. (Since the opinion was otherwise not widespread, that development created a simmering factional struggle within the Democratic Party.) In Washington, the idealism of the young left was embodied in Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a 29-year-old former bartender who offered unapologetically leftist policies, as well as an assured style that lacked the cringing self-consciousness of her her elders.

As always, commerce was ready to step in and exploit the new tastes of the young. Disney publicly embraced inclusivity, and while many of its efforts were patronizing or surface level, the company also released Black Panther, the most genuinely radical a mainstream superhero movie could get. Netflix positioned itself as the natural home for stories about underrepresented communities, which made things awkward when it then canceled them. Box-office successes like Girls Trip and Crazy Rich Asians demonstrated that diversity, aside from its other virtues, was profitable. But the fall of 2019 would reveal just how deep a modern corporation’s ideals ran. Though the NBA had spent the decade positioning itself as the enlightened sports fan’s favorite league, when Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey sparked an international controversy by tweeting support for democracy protests in Hong Kong, the entire league apparatus aligned with the Chinese government in denouncing him. The balance sheets had said championing progressive causes was savvy business sense; they said maintaining important relationships in a lucrative overseas market was too.

Hollywood often operates on a delay, and it wasn’t until the last year of the decade that studio films began responding to the Trump era, rather than anticipating it. What they showed was not pretty. In 2019, a string of films treated society as a zero-sum game between the haves and have-nots. Joker, Parasite, and Knives Out all depicted, with varying degrees of optimism, the folly of assuming the wealthy were on your side. Ready or Not and The Hunt envisioned a world where elites preyed on the poor for sport. (The latter would be literally canceled when right-wing media interpreted it as a fantasy about killing Trump voters.) The horror in Jordan Peele’s Us turned out to be the horror of revolution, the fear of the thumb coming off the societal scale.

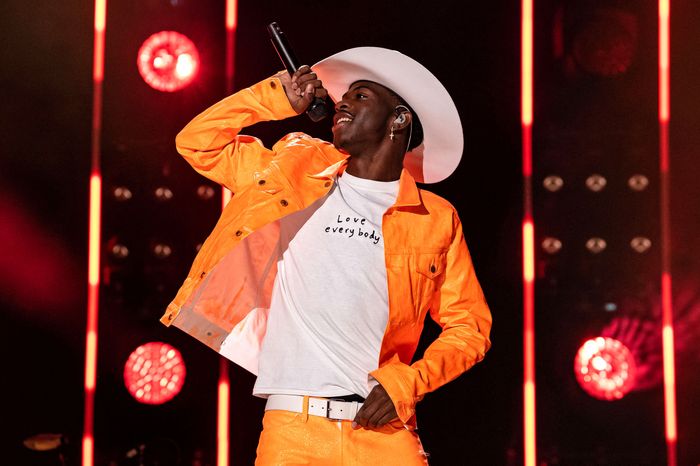

It made sense, then, that the generation that grew up in this world proved to be even more nihilist than the ones that preceded them. They were perhaps more powerful, too — with no illusions about the way the world should work, they could focus on the way it did. In music, young artists who’d spent the decade’s early years honing their creativity on outlets like Vine, SoundCloud, and Musical.ly arrived on the scene with their artistic identities fully formed. Budding rappers were so identified with their medium of choice that their brand of hip-hop — characterized by distorted trap beats, frequent benzo use, and raw teenage emotions — was dubbed “SoundCloud rap.” (By the end of the decade so many of them had died young that their generation was at a point of crisis.) On the more innocent end of the spectrum was Lil Nas X, a lovable Nicki Minaj stan whose debut single “Old Town Road” was created out of a $30 beat; the country-rap track became a novelty hit, topping the Hot 100 for a record-breaking 19 weeks in a row. And pop saw the arrival of Billie Eilish, the first A-list musician born after 9/11, whose dark gothic concoctions were recorded in a voice barely above a whisper.

Generation Z’s artists did not often sound alike, but their DIY vibes, facility with meme culture, and conversational use of social media marked them as the vanguard of a cohort that seems likely to define the coming age as firmly as millennials did the 2010s. There they’ll be facing off in an entertainment landscape dominated by tech giants, each of them launching a different streaming service to compete in a war for the American attention span. Can the small, the weird, the homemade survive in such a world? I don’t know. I wish the children good luck in the decade to come.

But when will that decade start?

It’s currently unclear which event, whether in the past or the future, will turn out in retrospect to have marked the end of the 2010s. However, given how singularly the past four years have come to be identified with one human man, the safe bet is that the moment of transition will come the day he leaves office. Whether that occurs through ouster, resignation, defeat, term limits, or death is a question likewise unable to be answered at this time.

Stray Observations:

• Scammers were not the only ones who could create their own reality. In one of those developments that seem to have both created and been created by Trump, technological change brought a sense of unreality to American life: There was fake news, and deepfakes, and on a shallower level, the selfie-editing app Facetune.

• By the end of the decade, independent film had been usurped as a driver of conversation by television. The career of Sam Levinson was particularly illustrative: His 2018 movie Assassination Nation was a Sundance sensation, but flopped in theaters; Levinson followed it up with the HBO series Euphoria, which covered much the same territory, and became one of the most talked-about shows of 2019.

• In one tiny blessing, the nation spent this era terrified that low-rise jeans were about to make a comeback. Thankfully, they never did.