This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Sales of Station Eleven are suddenly up. In Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 blockbuster hit, the “Georgia flu” wipes out over 99 percent of humanity — it moves so quickly that within 24 hours of the virus reaching America, all air travel is shut down. Cell lines jam, and phones stop working within two days. In under a week, television stations have gone to static as entire production crews die out. Spread via tiny aerosol particles, the Georgia flu is like our seasonal one and, yes, the coronavirus, on steroids — mercury-popping fevers, rattling coughs, respiratory distress, followed by death.

“I don’t know who in their right mind would want to read Station Eleven during a pandemic,” the perplexed author wrote on Twitter, to which her readers replied: We would. Inhaling a novel about a contagion that brings civilization to an end while news about COVID-19 sends hand-sanitizer sales vaulting doesn’t sound logical. But there can be something reassuring about taking in a fictional disaster in the midst of a real one. You can flirt with the experience of collapse. You can long for the world you live in right now.

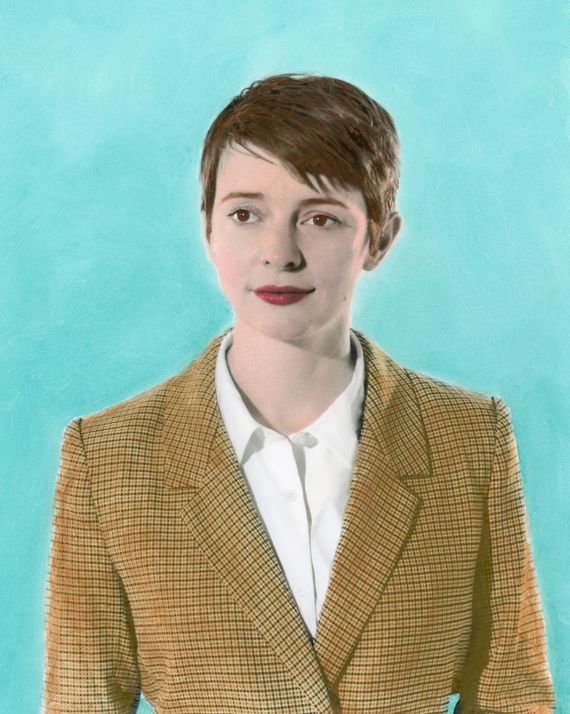

“The virus in Station Eleven would have burned out before it could kill off the entire population,” Mandel points out when I pose the question legions of fans are sending her way: Is she worried? The author is preternaturally-composed — dressed in a checked toffee blazer and mahogany boots, she has an air of Betty Draper just returned from riding lessons. “I sound reassuring, right?,” she asks, explaining that she thoroughly researched similar pathogens while writing. She also has a mischievous streak. Her face turns stoic. “It’s frightening, and we need to keep an eye on it.” Then she waggles her eyebrows: “Famous last words before the whole nation collapses!”

Station Eleven sold 1.5 million copies, a hit with sci-fi fans and highbrow-fiction devotees alike that elevated Mandel to literary stardom. Published after a mid-aughts deluge of postapocalyptic novels, it doesn’t fit the standard mold. Mandel isn’t interested in the flu’s aftermath, with the accompanying pillaging and clan-building. She imagines how society might have remade itself 20 years later. Readers loved that it bypassed the clichés of civilians turning against one another and instead made sense of chaos.

There’s considerable pressure on her follow-up, The Glass Hotel — so much so that her editor, Jenny Jackson, wrote a note to readers explaining that even a sales rep at Knopf confessed she was worried about reading it, that it “won’t live up.” Their fears were not borne out: The novel has already roped in gushing advance reviews, and it’s in its third printing, even though it doesn’t publish until the end of March.

The Glass Hotel, which has some prickling connections to the world of Station Eleven, revolves around disaster of another kind: a multibillion-dollar Bernie Madoff–style Ponzi scheme in 2008 Manhattan. Financial-crisis drama doesn’t have the same ring of excitement as, say, a deadly cough that flattens the world. But unlike Station Eleven, this is a disaster in which Mandel can point a finger at a perpetrator. It’s a story less interested in hope. It’s bleaker than the end of the world.

In the summer of 2015, Mandel was on her second tour of the U.K. for Station Eleven. She had just taken home the Arthur C. Clarke prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award. Late one night, she was in her hotel room booking plane tickets for her boss at Rockefeller University’s cancer-research lab, where Mandel had worked as an administrative assistant for seven years, when she realized the absurdity of her situation. Station Eleven had been such a smash success that she wasn’t even planning her own travel anymore. But here she was selecting seating assignments for someone else. “If you’re from a working-class background,” she says, “it’s really hard to let go of that day job.”

She did let go, spurred by a realization: She couldn’t do the job and continue to promote the novel, work on her next one, and parent her daughter, Cassia, now 4, with her husband, Kevin Mandel, a ghostwriter and headhunter. Station Eleven had done that rare thing, which even the most critically celebrated authors struggle to achieve — it gave her, she says, “more money than I ever would have imagined having in my entire life.”

Mandel is vague about what this means. “Nobody with money thinks they’re wealthy,” she offers, “but it’s enough to remodel my house. People who say that problems can’t be solved with money, I don’t know … Show me the problem!” The money, it seems, is more than just enough to remodel. She sold the TV rights to Station Eleven to HBO Max; The Glass Hotel has gone to NBC, and on the day we met, she was deep in pilot drafts. She’s 41, and she’s crossed over into another life.

Mandel grew up “very much without” money in a forest on Denman Island (“about the same size and shape as Manhattan, but with a thousand people”) off the east coast of Vancouver Island. It’s a place with two stoplights, “beautiful and claustrophobic.” She could feel the tenuousness of humanity’s hold over nature. “When you take it for granted water comes out of your tap,” she says, “you’re thinking differently than where I grew up, where we’d run out of water consistently in the summer and switch to a backup system.”

Mandel was homeschooled because of what she calls the inadequacies of rural education, her “counterculture” parents, and dance, which she pursued seriously until her early 20s. At 18, she left the island to attend the School of Toronto Dance Theatre without a high-school diploma or a GED (she didn’t need 12th-grade math to keep dancing, so she didn’t worry about it). By 21, her passion for dance had waned. She bounced around Toronto, Montreal, and New York. To support herself, she worked jobs like manning the stockroom of a now-shuttered Montreal chain store, Caban, where she earned $8.50 an hour, showing up at 7 a.m. to unload trucks. “There were mornings when it was minus-20 Celsius,” Mandel recalls. She liked the nature of the work — her characters, too, are often settled in hands-on, rhythmic jobs like tending bar.

The story of how Mandel began writing is almost odd in its lack of velocity. As part of her homeschooling curriculum, her parents had asked her to write every day, and the habit stuck with her. Mandel knew a novelist in New York — “somebody not terribly well known, maybe let’s leave the name out” — who made her realize it could be a career. She put her mind to it, just like that, without a single formal class or any professorial encouragement. The first thing she really dug into turned into her debut novel.

In 2006, after four years of writing, she had finished Last Night in Montreal, about a young woman with a peripatetic childhood who can’t stop fleeing the lives she creates. Her agent at the time, the late Emilie Jacobson of Curtis Brown, understood her work implicitly. She submitted it to 35 publishers, one by one, waiting to hear back from each before sending it on to the next. Two years later, it was bought by Unbridled, a small house that published her first three novels, all noirish mysteries. They’re so distinct from Mandel’s current preoccupations that they seem to come from a different author. Each sold a few thousand copies and earned small industry press, especially in France, where she was beloved on the crime circuit.

“I’ve always seen myself as writing literary novels with the strongest possible narrative drive, which pushed me in the direction of genre,” Mandel says of her early work. But she yearned for a broader audience and felt that if she kept going down the same path, she’d end up “boxed into that marketing category.” She decided to do something entirely different for her next book. It began as a story about a Shakespeare troupe, a way for Mandel to write about theater and her experience with dance. But as a child of the forest, she wanted to see what her characters might do without technology. That’s when the idea of a global calamity came to mind. She placed her troupe in a dystopian setting, traveling through what was once Michigan, offering kinship through art.

Her agent sent out the Station Eleven manuscript, and while the then-34-year-old Mandel paced her family’s living room, an auction with six publishing houses ensued. It would go on to blow past all her parameters for how successful a novel could be. “It just kept ballooning,” she recalls. The book was a BuzzPick at BookExpoAmerica, a surefire indicator of commercial salience, and a Title Wave selection inside Random House, which meant the publishers threw their full weight behind its promotion. The five-city tour mushroomed into 17 cities, then spread around the globe. Year-end lists “rained down on us,” Jackson said. “That’s when sales really spiked.” They reached 450,000 after a year. Then it sold a million more copies.

The first sentence of The Glass Hotel that Mandel put to paper is now in the middle of the novel. A Greek-chorus-like collective of Wall Streeters who work at doomed billionaire Jonathan Alkaitis’s financial firm suddenly begins to speak: “We crossed a line, that much was obvious, but it was difficult to say later exactly where that line had been.”

The we in question are party to “The Arrangement” — the falsifications required to prop up a multibillion-dollar Ponzi scheme. At this point in the story, we already know Alkaitis will end up in a white-collar prison for the rest of his life, but this rewind back in time to the brink of collapse turns it from a ripped-from-the-headlines high-art form into a careful, damning study of the forms of disaster humanity brings down on itself.

Alkaitis’s employees are gathered in a conference room to hear him explain that the company has liquidity problems — meaning, they can no longer steal from one investor to pay back another. We then learn about the next 24 hours for each of them: who stays to drunkenly shred papers, who spends hours mindlessly liking Facebook posts, who calls the FBI. The details are similar to those newspapers relayed after Madoff’s sandcastle washed away in 2008. But Mandel is careful to note “the Madoff character is not Madoff. His family is not Madoff’s. But the crime is the same. The crime is what fascinated me.”

The author professes a good deal more anxiety about economic collapse than cough-splatter pandemics. It’s hard not to wonder if now, a secure future in hand, Mandel worries about being kicked out of the kingdom of money. “I sold The Glass Hotel in a partial,” she explains, “which I normally would never do. I’ve always finished a novel before I sold it, but I was pretty sure the economy would inevitably collapse under Trump.” It’s also personal. A close family member, whose identity she doesn’t want to disclose, invested with Madoff. “I think they had put in $100K, and it performed well, obviously, because the funds were totally fictional.” This relative wasn’t financially ruined — Mandel calls them “the lucky minority who got more money out of the fund than they put in.” They had simply trusted.

Like Station Eleven, Mandel was drawn to a narrative of downhill momentum. But the books differ in fundamental ways. Reading Station Eleven is a soothing experience. Connections align. There is a definitive before and after. The world settles into something new. You can fear a pandemic, but you can’t rage at one. The Glass Hotel doesn’t offer the same reassurances. With a Ponzi scheme, there’s a clear villain, which is a narrative boon. But the disaster, perhaps because humanity caused it, feels crueler. What do we do when the world explodes, it asks, but most of the population carries on as before? Like the rest of Mandel’s work, there are characters all over the globe — from parched Dubai terraces to the extravagant boutiques of Fifth Avenue. This sort of global wandering is too often gushed about in jacket copy, as if a variety of locales are a substitute for other kinds of expansiveness, but for The Glass Hotel it’s central to the premise that the world’s interconnectivity magnifies calamity. In this case, a tsunami of manipulated zeros and dollar signs that washed away the lives people had imagined for themselves.

It also gives weight to disaster’s unbearable banality. The Glass Hotel, notably, includes a shipping executive whom Station Eleven readers will remember: Leon Prevant, who, in this iteration of his life, invested with Alkaitis. Just before Leon discovers his life savings are a fabricated string of numbers, he’s in a meeting with a colleague who was his secretary in the parallel universe of Station Eleven. They’re discussing the economy’s general downturn when she wryly says, “There’s something almost tedious about disaster. Don’t you find? I mean, at first it’s all dramatic, ‘Oh my God, the economy’s collapsing … but then that keeps happening, it just keeps collapsing, week after week.’ ” In a novel full of Easter eggs for devoted Mandel fans, it’s a sly note of camaraderie. And in a world where rolling disasters fade into one another, it’s a reminder that Mandel wants to lurch us out of the tedium.

*A version of this article appears in the March 16, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!