In a time of global pandemic, when people are shut in their homes and more vulnerable than ever to the siren song of Netflix, everyone in America has simultaneously become obsessed with Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.

At least it feels that way. The docuseries — part work of true crime, part graphic nature documentary, and part trashy reality show — has become must-see television for anyone who wants to remain pop-culturally conversant, or at least have something to talk about besides the coronavirus. I understand why. It’s an extreme, flawed example of the types of docuseries and documentaries that have generated the most attention over the past five years. Let’s call them WTF docs.

As that title would suggest, WTF docs are documentary series or films with so many jaw-dropping twists that they make you blurt out, “What the f- - -?” at least once, and usually multiple times. A lot of true-crime shows fit into this category. Certain revisitations of historical events or scandals — Wild Wild Country, Leaving Neverland — do, too. Even documentaries that tackle comparatively lighter subjects, like McMillions or last year’s two Fyre Festival movies, fit into this subgenre because they also are rife with unexpected, outlandish moments. “You’ve gotta see this,” we tell our friends after watching one of these documentaries. “It’s crazy.”

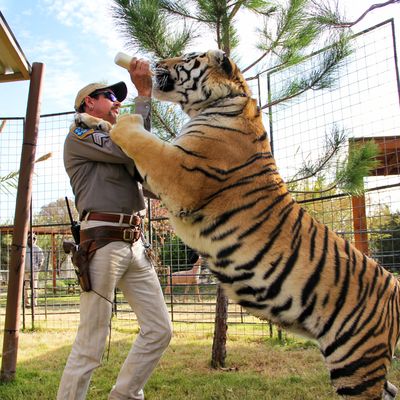

Tiger King is definitely a WTF doc. It’s got lions, and tigers, and bears — already an “oh my!” — but also chimpanzees, a monkey that appears to live exclusively inside the shirt of Wildlife in Need owner Tim Stark, and tons of expired meat from Walmart that is fed to many of these animals. The protagonist, roadside zoo owner Joe Exotic, is, to quote a description of him from the docuseries, a “redneck, gun-toting, mullet-sporting, tiger-tackling, gay polygamist.” He winds up in jail for his involvement in a murder-for-hire plot to kill Carole Baskin, an animal-rights advocate who shares his passion for large jungle cats and has been accused, with no definitive evidence, of killing her second husband and feeding his remains to her tigers. Before going to jail, Joe mounts two failed political campaigns, one for president and one for governor of Oklahoma. Joe Exotic is basically what the acronym “WTF” would look like if it were turned into a person.

I haven’t even scratched the surface of the abundance of bizarro in Tiger King, but if you’ve seen it, you already know about it, and if you haven’t, well, you get the idea. It’s a wild, wild story, and the filmmakers embraced that. “It had all the ingredients that one finds salacious,” Eric Goode, who co-directed Tiger King with Rebecca Chaiklin, told the New York Times. “So we knew that there would be an appetite for it.” They were right. But there’s something about Tiger King that doesn’t sit well, that feels ookier than other recent WTF docs, and I think it comes down to this: Tiger King is very aware of its own WTF-ness.

Where other docuseries and documentaries come upon their jaw-dropping plot twists in a manner that feels organic, the storytelling in Tiger King seems to be guided by them. Goode, a businessman and conservationist, says he originally intended to focus the docuseries on the exploitation of exotic animals, but the final product suggests that the insane drama and quirky people in this world superseded that plan. The WTF-ery became Tiger King’s entire reason for being. Its WTF-ness provides its oxygen.

Tiger King is an attempt to make a documentary about a guy who, as we learn from the seven episodes, has always wanted to be a reality star. For that reason, the series inevitably ends up with a bit of a lowbrow reality vibe: a hint of Honey Boo Boo and a faint whisper of Duck Dynasty. Joe is a volatile, flamboyant narcissist who does things that are patently ridiculous. It’s impossible to watch what he does — and what some of the other interviewees do and say — without laughing. I laughed several times while watching it. (Personal favorite line, from Joshua Dial, the libertarian who worked as Exotic’s campaign manager: “I already knew he was batshit crazy from our conversations at Walmart.”)

The figures who appear on-camera provide plenty of laughs simply by being themselves. But the filmmakers sometimes give in to the urge to push things further toward mockery. The lengthy clips from Exotic’s music videos are overused. We get that he’s an attention whore and that he is not a talented pop star, but at a certain point, the videos aren’t serving any function other than to make the audience cackle at Joe’s expense. Another example: After James Garretson, who was tangentially involved in the murder-for-hire scheme and testified against Joe Exotic during his trial, says he may have incriminating evidence about other people in the private-zoo realm, the show cuts to a shot of Garretson riding a jet ski while Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger” plays on the soundtrack. It hammers home the idea that Garretson is full of himself, but it also seems cheap and unnecessary, like a ploy to inspire memes. Which, of course, totally worked.

It’s worth noting that other WTF docs have zeroed in on people who are ridiculous and/or maddening without resorting to such tactics. One of the WTF-iest docs I have ever seen is Abducted in Plain Sight, about a girl who was kidnapped in the 1970s — more than once, mind you — and sexually abused by a family friend while her parents sat on their hands and each became sexually involved with the kidnapper. Unlike the people in Tiger King, Jan Broberg, the victim, and her parents look relatively normal on the surface, but the situations they describe are bonkers. On more than one occasion, I’m sure director Skye Borgman wanted to shout “What the hell were you people thinking??” She didn’t, or at least doesn’t on film. Instead she takes a restrained approach, trusting that the audience will grasp how outrageous this story is with no need for embellishment.

Hulu’s Fyre Fraud doesn’t shy away from having some fun with its subjects — Billy McFarland, JaRule, and everyone involved in planning the disastrous Fyre Festival. McFarland is often described in snarky terms by former colleagues and journalists who covered the fiasco. But when Fyre Fraud pokes fun, it mostly does it at the decisions made by McFarland and co. Because he’s wealthy and acted out of a sense of such privilege and hubris, any pot shots at his expense feel pretty justified. Fyre Fraud punches up, where Tiger King, populated largely by people who are poor and living on society’s margins, skates really close to punching down and making the audience feel complicit in the jabs.

There is also a lack of depth to Tiger King that turns it into an increasingly empty exercise. Docuseries don’t have to change the world, but the best ones have a sense of purpose. The Jinx examined how a wealthy psychopath, Robert Durst, could manage to get away with murder for decades, and in the process, played a key role in putting him behind bars. Making a Murderer raised questions about the handling of a murder case and highlighted broader problems within the justice system. Fyre Fraud and its Netflix cousin, Fyre, while allowing us to relish in the many layers of screw-ups involved in completely ruining a luxury retreat for the Instagram set, also raise questions about influencer culture and the hunger for status, or at least the appearance of it.

Though it touches on the abuse of exotic animals and the problematic aspects of owning them, Tiger King doesn’t dig as deeply into those issues as it could have. The point of Tiger King, at its core, is “look at all this weird shit that happened.” But a docuseries, or any work of journalism or pseudo-journalism, should have a broader sense of purpose that makes its story relevant. It’s possible to mix surprising twists that will become Twitter fodder with that kind of purpose. But Tiger King can’t figure out how.

The major players in this show, with a few notable exceptions, are awful individuals who can’t be trusted. Even Baskin, who is an oddball in her own way but seems more in control of herself than Joe, has those murder rumors hanging over her head. As the docuseries progresses, we learn new details about all of these people, but we don’t learn things that widen our understanding of them. Contrast that with a truly great WTF doc, Wild Wild Country, about the clash between members of the Rajneeshpuram commune and residents of a small Oregon town where the commune settled in the 1980s. Throughout the six episodes of that Netflix original, directors Chapman and MacLain Way changed my mind repeatedly about how to perceive the tensions between the residents of the town and those who followed the teachings of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, in some cases to the point of committing crimes. The Bhagwan’s right-hand woman, Ma Anand Sheela, does horrible, horrible things — I don’t want to spoil this for others, but let’s say some mass poisoning is involved — and yet I found her gutsy and kind of a badass at the same time. Nothing is fully black and white in Wild Wild Country, and that’s what makes it thought-provoking in addition to being a nonfictional roller-coaster ride.

Tiger King, though, is primarily colored in black and white, and not just because of all the animal prints. At the end of the series, some may feel a certain measure of sympathy for Joe Exotic, who is in prison and clearly in a bad place. But our understanding of who he is and what motivates him hasn’t deepened much since the first couple of episodes. In the last installment, right after we hear audio of Joe on the phone from prison, tearfully talking about how he shouldn’t be there, the show immediately cuts to footage of Baskin and her husband drinking Champagne after learning that Exotic, who repeatedly threatened to kill her over the years, has been convicted. It’s an abrupt and manipulative piece of editing that casts Exotic as a victim and Baskin as the heartless rich lady celebrating his bad fortune. The reality is much more nuanced than that.

What’s missing in Tiger King is nuance, but also a greater sense of humanity and more journalistic — or at least journalistic-adjacent — integrity. The series can certainly be exciting. WTF docs are always exciting. But the really good ones are more than that. At one point in Tiger King, a TV reporter in Oklahoma describes Joe Exotic’s appeal this way: “Even if it’s a train wreck, you can’t help but look.” That’s what Tiger King is. A train wreck you can’t help but look at — nothing more, nothing less. Maybe that’s why Americans are responding to it with such enthusiasm. When the whole world has become a massive, deeply distressing train wreck, the only thing that can fully distract us is another, less alarming train wreck.