Every week for the foreseeable future, Vulture will be selecting one film to watch as part of our Friday Night Movie Club. This week’s selection comes from staff writer Rachel Handler, who will begin her screening of Almost Famous on June 26 at 7 p.m. ET. Head to Vulture’s Twitter to catch her live commentary, and look ahead at next week’s movie here.

Last month, I interviewed Cameron Crowe about Vanilla Sky, his polarizing 2001 sci-fi thriller about a man (Tom Cruise) who loses everything after he loses his (Tom Cruise) face. Vanilla Sky was a significant departure for Crowe, whose films are usually rooted in some form of reality; the dark, unsettling fantasy didn’t sit well with some of his fans and critics, who ostensibly wanted another story about a man who failed in a wildly public fashion, teetered on the brink of his own sanity, and then fell in love, rather than a story about a man who pays a lot of money to exist forever inside his own dream. But I am here to argue that, in actuality, the most fantastical film Crowe ever made was his autobiographical 2000 dramedy Almost Famous.

Almost Famous is, by Crowe’s own admission, based on actual things that happened to him: He went on tour with a bunch of famous rock bands as a teenager, got published in Rolling Stone, became friends with his artistic heroes, and went on to have a successful career in journalism and filmmaking, unmarred by the concept of “pivoting to video.” Watched through the lens of our current moment, when reporters are being laid off in droves, when structural racism and sexism run rampant and unchecked, when our futures hang in the fickle balance of the Facebook algorithm and hinge on the equally fickle whims of publicist gatekeepers, Almost Famous feels like pure whimsy — a Disney film, a story you tell your kids at bedtime after they ask you, “Mommy, is Mark Zuckerberg going to auction off my private data to the highest bidder before I can even legally consent to its distribution?”

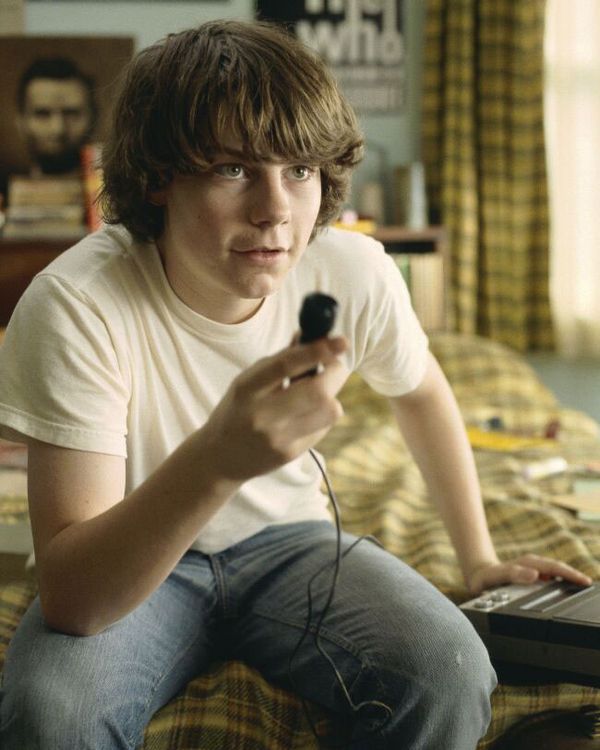

I first saw Almost Famous as a kid. It felt like a fairy tale then, too. I couldn’t believe that what I was watching actually happened to someone, more or less — and that I could someday attempt to re-create it. I still remember watching, mouth agape, as a teenage William Miller (Patrick Fugit) hopped onto a tour bus and befriended a bunch of rock stars, lusted after the ineffably fascinating Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), ignored his concerned mother (Frances McDormand, whom I now identify with perhaps more than anyone in the story), lost his virginity in a gentle orgy featuring elaborate scarves, and was rewarded for it all with a Rolling Stone cover story. At 13, I couldn’t fathom a career more exciting. I wanted to write about the art that I loved, to devote my life to digging deep into the things and people that mattered most to me. I also wanted to get drunk backstage in a Penny Lane coat.

I’ve been lucky to have been employed as a culture journalist for as long as I have, at outlets where I’ve mostly been supported and pushed and given time and space to grow, and, through sheer chance, only been caught in an unceremonious layoff once (so far). I’ve even had a few Almost Famous moments, like my surprising and strange correspondence with Fiona Apple, or the time Harry Styles wrote an entire album about me and then pretended it was about someone else. But all of these things make me something of an outlier. I have watched my friends and co-workers and peers get shoved through the journalistic wringer (no pun intended) more times than I can even count at this point. The unavoidable fact is that journalism in 2020 looks absolutely nothing like it did during Crowe’s charmed youth. (Much has already been written about this topic by people much smarter than me, so I will mostly use this as a space to complain and make detached jokes about our rapidly winnowing field.) In some ways, that’s a very good thing. For example, it’s frowned upon these days when journalists fall madly in love with their subjects, hang around them until they overdose on quaaludes, then kiss them while they’re totally unconscious. Ethical boundaries have been put in place that prevent (or at least attempt to prevent) the sexual murkiness that once pervaded the sort of male-driven, male-centric, Hunter S. Thompson–y journalism hinted at in Almost Famous. And though we’ve got a long, long way to go in terms of any sort of racial and gender parity across the industry, white men are no longer the only people who get their stories featured on the cover of Rolling Stone.

But much of what made journalism attractive to newcomers in the age of Almost Famous has been co-opted or destroyed by a bunch of greedy men hiding out in the Hamptons. Here are just a few things that happen in Almost Famous that are more fantastical now than the notion of running through an empty Times Square: A male music journalist is extremely kind. (I know, #NotAllMaleMusicJournalists.) That male journalist achieves his dreams via hard work and gumption and honesty, rather than by asking his finance-bro dad to email one of his friends in publishing. A big-time editor takes a chance on a young, unknown writer, sight unseen. That writer is provided with structural support and a significant amount of editorial freedom. He is allowed to spend many months writing a single story, instead of juggling several pieces at once because of a rapacious global audience’s expectation for more content, accessible and updated 24/7, and for far less money. A strong emphasis is placed on factual accuracy. There are, for the most part, no publicists involved, which means the interviews aren’t interrupted if the journalist or subject veers “off message.” There seems to be an unlimited budget for incidentals. Nobody mentions SEO or a billionaire looming behind the scenes, contemplating running for president. Nobody runs an op-ed that endangers staffers lives. Nobody is blindsided by a layoff that leaves them without health care. Nobody tweets.

So why should we rewatch Almost Famous now, what with all its potential to depress us? Because while we wait for a better business model, for a dismantling of the bigoted systems currently in place in our industry, for more time and money to develop new writers and send them on rambunctious tour buses with their heroes, we might as well enjoy the film for what it is: entertaining science fiction. Also, and if nothing else, the music is freaking amazing. Listen to it with a candle burning, and you’ll see your entire future.

Almost Famous is available to stream with a Hulu or Showtime subscription, and is available to rent YouTube, Google Play, Vudu, Prime Video, and iTunes.

If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.