It feels like I’ve been a Fiona Apple fan my entire life. I know that isn’t true, though, as my introduction to her was the “Criminal” video, which came out when I was around 10. But I loved it and her instantly. I still listen to her constantly, and still remember the skip in my first When the Pawn CD, right at the end of “I Know.” (My new When the Pawn CD, for my car, and the When the Pawn CD I purchased earlier this year for my boyfriend’s car do not, I’m disappointed to say, have the same skip.)

I got the chance to see her my freshman year of college at the Tower Theater in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. I went with my friend Lee, who was also an enormous fan. Our friendship was new (and brief; I don’t know her anymore), but we went and sang and cried and screamed together, and it felt remarkable, seeing this woman I felt I knew so intimately in front of me, banging on a piano, flopping around, fully alive.

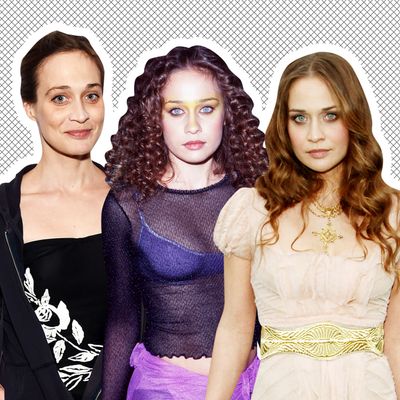

The most remarkable part of the night came after, though. (Please lean in close, listening with rapt attention.) Back in the hallway of our freshman dorm, my new friend Lee looked at me and said, “You know …” She paused for dramatic effect. “You kind of look like Fiona Apple.”

Me? Me?! I couldn’t believe it. Never has a greater honor been bestowed upon me than that I, at least in that particular lighting, in that one moment, looked — kind of — like Fiona Apple. My hero!

Below, in honor of Fiona Apple’s newest album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, my co-workers wax nostalgia about their own Fiona Apple memories.

It’s 2003, which is several years after Fiona Apple released both Tidal and When the Pawn, but they’re new for me because I just downloaded them on Limewire. “Criminal” is my favorite song but “I Know” matches the melancholy I feel every afternoon at middle-school rehearsals for The Hobbit, where I am pining for the boy who plays “Dwalin” (Dwalin is a dwarf with a lot of lines. I’m a hobbit with one line, but it gets cut). When she sings, “And you’ve early closed your curtains, I’ll wait by the backstage door,” it could not be more literally about me. —Bridget Read, writer

When “Criminal” came out in 1997, I was 16 and Fiona Apple was 20. “There’s this music video with a girl who looks like me,” I said to my mother. “Maybe she’s Jewish,” replied my mom, who had not seen the video. Fiona Apple at 20 only looked like me at 16 in vague outline: full lips, brown hair. But I could tell I was supposed to relate to her, and I didn’t like it. I was not a “bad bad girl,” and I thought it was extremely uncool to claim to be one so that horny record executives would give you an album. This is, of course, not a popular stance now, and it wasn’t a particularly generous one back then. I was innocent and self-righteous at 16; three or four years later, the mood of “Criminal” made more sense to me. But even now, I can’t hear it without remembering that unsettling feeling: Am I supposed to be this sexy and tormented? Do I have to be? Is this what being a woman is? In retrospect, of course, that’s exactly what makes it powerful. —Izzy Grinspan, deputy style editor

Truthfully, Fiona Apple is not a name that draws my attention … but I was curious about Fetch the Bolt Cutters after reading Pitchfork’s review, which gave her a rare, perfect 10. Now I’m regretting the time I just glanced over her name. I think I would’ve appreciated Fiona the most when I was 19, brand-new to New York City, and woefully lonely in my sublet apartment. It wasn’t true, of course, but at the time, it felt like I was the only one who had ever moved to the city with no friends and no connections. Listening to Fiona’s angst would’ve probably been a great match for mine. —Daise Bedolla, social media editor

Although I’ve been an enormous fan of Fiona Apple for as long as I can remember, I think probably the most emotionally effective thing she’s ever written, for me, is a letter she wrote to her fans in 2012. She posted it on Facebook, to announce she was canceling a South African tour because she needed to be home with her dying pit bull, Janet. “I know that she’s not sad about aging or dying,” she wrote. “Animals may well have a survival instinct, but a sense of mortality and vanity, they do not. That’s why they are so much more present then most people. But I know that she is coming close to point where she will stop being a dog, and instead, be part of everything.” As a dog obsessive, I’ve read a lot of writing about them, but I think those lines are just the best out there. —Kelly Conaboy, writer-at-large

Maybe this is a cop-out, but I feel like I’m a different woman every time I listen to Fiona Apple. When I was a teenager, I remember seeing the “Criminal” video for the first time and I had no idea how to register it. Later in my teen years, “Never Is a Promise” became my go-to heartbreak song, even though then I truly had no idea what heartbreak could really be like. As things change and as I change, it’s corny but true — Fiona and her music have remained one of my only constants. I remember listening to “Not About Love” in my sunny Los Angeles apartment while I aimlessly (and unfortunately) dated every comedian in sight. On cloudy days, while taking the train to the office, I sometimes just ached for the gut punch of the back-to-back of “Get Gone” and “I Know” as I absorbed the many faces of the L train. I’m a different woman every time I listen to her, but Fiona’s made me a more honest one at least. —Kerensa Cadenas, senior culture editor

“Valentine” still reminds me of the miserable last few months of a dying relationship, as my then-boyfriend was planning to move across the country. This was several years ago, when few things felt as tragic as watching someone achieve their dreams while I failed to achieve any of my own. (“Cramped up in the learning curve,” indeed!) Now it’s almost nice to look back on? (I know, I know.) (Still.) —Jordan Larson, essays editor

Fiona Apple will always make me think of the living room of the apartment where I lived with my three best friends my senior year of college. “Living room” is sort of an overstatement. In retrospect, I’m pretty sure the apartment was a converted attic, and the one common room was barely big enough to fit a table and a love seat we found at the Salvation Army. That was where we congregated to eat microwaved leftovers and in theory do homework, but mostly where we painted our nails and talked about crushes. In my memory, it’s always fall, and Fiona Apple is playing softly in the background. —Erica Schwiegershausen, editor