Sometimes you just want to watch some magic. You want someone to shuffle some cards around faster than your screen-dazed eyes can follow; you want a fast-talker to pressure you ÔÇö lightly ÔÇö to agree that something is amazing; you want to be startled by one card of a 52-card deck winding up in a rather unexpected position. You assumed the jack of hearts was over here, but no! He is over there! That is just about the level of shock I can sustain right now in my entertainment viewing.

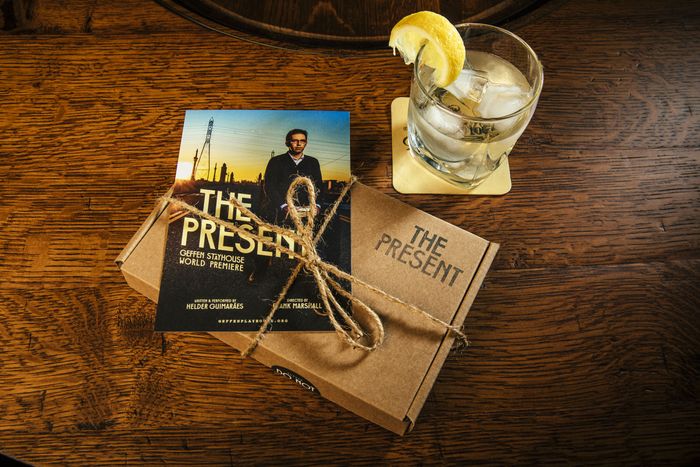

By magical coincidence, thereÔÇÖs a show just like that streaming from the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles: Helder Guimar├úesÔÇÖs The Present. ItÔÇÖs solid showmanship and ephemeral pleasure; itÔÇÖs warm storytelling and cool audience interaction. The best part is how long the show is ÔÇö not the swift hour of its livestreaming presentation but the long and rather delicious anticipation thatÔÇÖs built into the preshow. A short while after you buy your ticket, a cardboard box arrives in the mail (which is already analog wizardry), and youÔÇÖre not allowed to open it. Your Present present sits on your coffee table, tied up with string, making all kinds of silent promises, until the virtual audience gathers at the appointed Zoom time to open them together.

Guimar├úes shapes his card-trick act around a story of his own quarantine ÔÇö a childhood illness, stuck at home, falling in love with a deck of cards. HeÔÇÖs also full of tales of his slightly mysterious grandfather, whom he understood, in many ways, too late. Magic shows are full of looking backward: I absorbed more history at a show by Ricky Jay (God rest him) in which he hurled playing cards at watermelons than I ever did from some dusty old book. You gotta get my attention, I thought at the time, while Jay flung magiciansÔÇÖ lore at us, fast as weaponized face cards. Guimar├úes is looking backwards too, though not at a legacy of flimflam artists and high-deceivers. HeÔÇÖs focused on memories of a decent man, living at the periphery of his grandsonÔÇÖs mind, even long after his death.

Guimar├úes himself has a sorrowful aspect, even when heÔÇÖs convincing us through sleight of mind to do our own tricks, on ourselves. His eyes are a little sad, even when everything turns out just the way he wants, every time. Armed with cards heÔÇÖs sent us (and various other items from that cardboard box), we turn out to be very good at creating ordered stacks out of seeming chaos and coming up with just the card that Guimar├úes was thinking of. ÔÇ£You are doing the magic!ÔÇØ he cries at us, as he suddenly fans out an obedient deck, somehow rearranged in order. He lets us know too early that his shuffles canÔÇÖt be trusted, which takes away a little of the surprise ÔÇö of course the jack of hearts is where he wants it to be, since the cards dance under his hands like marionettes. Still, the cards are inherently lovely objects, and seeing his very real choreography of them ÔÇö disorder, order, disorder again ÔÇö is more pleasurable than some mere illusion.

I recommend The Present for the way Guimar├úes reframes enforced isolation as a portal to mystery but also for the way the show helps keep your in-person attendee skills fresh. Remember that leaning-forward feeling of being present at a performance that needed your alert attention, that wonderful requirement theater puts on you to hold up your end of the show? Actors talk about a ÔÇ£good houseÔÇØ and a ÔÇ£supportive audienceÔÇØ because thereÔÇÖs an energy loop that has to connect through us. (If no one laughs at a comedy, it isnÔÇÖt a comedy anymore.) In The Present, I felt that sizzle again of being part of Guimar├úesÔÇÖs creation. I couldnÔÇÖt simply be passive ÔÇö our mics were on, and I needed to ooh and aah to keep the magical mood alive. The quarantine has made certain kinds of contact feel immensely precious: Zoom audiences with strangers are certainly fun and voyeuristic, and getting a package that I didnÔÇÖt order myself from Amazon was a low-key spell for delight. But it was this third kind of contact, the audience-plus-performer spark, that makes The Present such a gift.

Because ÔÇö what exactly makes something feel ÔÇ£liveÔÇØ? Not what is technically considered ÔÇ£live,ÔÇØ which just means we are watching something as it happens. Rather what actually registers with a watcher as the sensation of ÔÇ£livenessÔÇØ? When weÔÇÖre told weÔÇÖre watching a live concert, weÔÇÖre often settling for something that was simply captured live ÔÇö the recorded event or YouTubed Zoom performance. These videos sometimes contain a little of their original conditions, but we arenÔÇÖt watching a ÔÇ£nowÔÇØ anymore. WeÔÇÖre watching ÔÇ£then.ÔÇØ

As The Present does, several of the more sophisticated recent digital theater productions use interactivity to draw a bright line around their liveness, to remind us repeatedly that we are sharing a common ÔÇ£now.ÔÇØ In Creation TheatreÔÇÖs The Time Machine, a Zoom performance from London (tickets still available through June), the production spends quite a bit of time showing the audience to itself ÔÇö we frequently show up in gallery view, doing as weÔÇÖre told, whether thatÔÇÖs clutching a household object or wearing a silly outfit. The main players are a series of actors, who travel through time (various Zoom backgrounds) in a bid to save us from a dystopian future. Jonathan HollowayÔÇÖs script for The Time Machine is muddled (time travel is a danger, and we must prevent it, but only by doing time travel, to Studio 54?), though itÔÇÖs been made very much in earnest, with a post-show panel by the showÔÇÖs consultants at the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities. But the type of the interaction is informed by British pantomime ÔÇö I sometimes felt like a child being encouraged to clap for Tinkerbell rather than an adult being asked to think harder.

Each of these productions do, though, teach the industry about an emerging art form. I spoke several weeks ago with Michael Wheeler, the director of artistic research at CanadaÔÇÖs Folda Festival of Digital Art. (It is livestreaming through June 13.) ÔÇ£WeÔÇÖre really at the beginning of the rules of new creation,ÔÇØ Wheeler said. The pieces IÔÇÖve seen in this yearÔÇÖs Folda have been contemplative and often gorgeous ÔÇö particularly Jose RiveraÔÇÖs dreaming music stream, or This World Made Itself, Miwa MatreyekÔÇÖs video work, in which she sends her own shadow across a mysterious fantasy landscape. Wheeler also recommended a piece that was at a past Folda called Good Things to Do, an immensely effective dream journey, which unfolds as a written event that the virtual audience reads silently on their own screens. In its live performances, the showÔÇÖs creator, Christine Quintana, has the audience actually type their way into the script. It contains the most finely choreographed online ÔÇ£surpriseÔÇØ IÔÇÖve experienced, as well. ┬á

Still, my favorite interactive events of the last many months have been Seven Daughters of Eve Thtr. & Perf. Co.ÔÇÖs monthly gatherings, each one a ÔÇ£contemporary religious serviceÔÇØ for a strange new religion, Fem-Animism. We ÔÇ£joinifyÔÇØ by donating on Patreon, and then weÔÇÖre beckoned into a weird and soothing online ceremony, full of sacred washing, speaking puppet crows (CORVID-19 can be very rude), astrological readings, and radical re- and de-centerings. Playwright Sibyl Kempson and her collective dance in their backyards or their living rooms, fade glitchily into their forest Zoom backgrounds, and give tongue-in-cheek sermons on their foray into the Big Money of donation-based religion. And then at the end of each, the congregation ÔÇ£gathers.ÔÇØ Again, in gallery view, we see the dozens of faces of those who have chosen to spend their time in this odd and beautiful way, as a musician strikes a bell tone from a singing bowl. The chime works as it does in other religious services ÔÇö it calls our attention both inward and outward. Looking calmly at all those faces as it sounds, you hear its healing message. DonÔÇÖt worry about later, it says. It is now, it is now, it is now.

More From This Series

- Old Patterns and Bold Stitches: The Blood Quilt

- Divas at Dusk: Death Becomes Her as Broadway Camp

- Out to Sea and Back With Swept Away