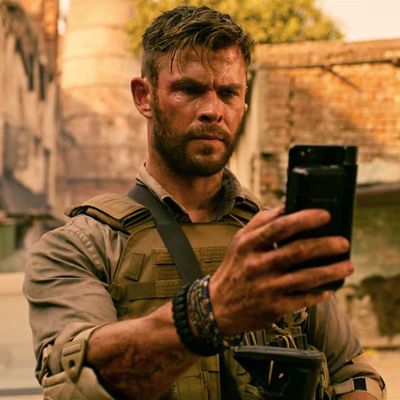

Last week, Netflix released some data about its most popular titles, and as usual, it all smelled a little fishy. The recent Chris Hemsworth action flick Extraction was apparently the most popular Netflix Original of all time, with 99 million views, followed by the 2018 Sandra Bullock thriller Bird Box with 89 million and March’s Mark Wahlberg mystery Spenser Confidential with 85 million. These numbers aren’t lies, exactly, but as many have noted, what Netflix characterizes as a “view” has been a fairly mutable thing as of late. Up until early this year, Netflix defined it as users watching at least 70 percent of a movie or a single episode of a series. In January 2020, however, the company announced that it now defined a view as something that was watched for at least two minutes.

Let me say that again: two (2) minutes.

That means that if you started watching Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga, you haven’t even gotten to “Volcano Man” yet — and that’s the second scene of the picture.

This whole business over the two (2) minute view caused quite a bit of controversy at the time, as chronicled by Vulture’s Josef Adalian in his “Buffering” newsletter. Netflix says two (2) minutes is “long enough to indicate the choice was intentional,” which is an interesting thing to say on a subscription service where watching something specific doesn’t really cost you anything extra or make the service any money. I’ve certainly let things play for a few minutes while I went and got a drink or took a bathroom break or whatever. By this logic, I am now a Hannibal watcher, even though I have never sat through an episode of Hannibal. (And, yes, I know. I should watch Hannibal.) More ominously, I am apparently one of the 83 million viewers of Netflix’s Michael Bay opus 6 Underground even though I fell asleep after the first ten minutes and turned it off halfway through.

But, hey, at least Netflix is reporting something. Its numbers might be dodgy, but they’re a lot more specific than the downright Soviet obfuscation we’ve gotten from Apple TV+, which recently leaked to Deadline the highly classified and earth-shattering news that its Tom Hanks WWII thriller Greyhound “turned in a viewing audience commensurate with a summer theatrical box office big hit.” Around that same time, a Hulu insider, presumably hiding in the shadows of an underground D.C. parking lot, revealed to IndieWire that the streaming service’s recent release Palm Springs “broke the streaming platform’s opening weekend record by netting more hours watched over its first three days than any other film on Hulu during the same period.” How many hours was that? What was the previous opening weekend record? Held by whom? Don’t ask us, we’re just massive tech companies that harvest acres of data from every single thing you do.

By Apple and Hulu’s standards, Netflix seems downright transparent. The streamer did tell us that The Old Guard, its big release over that same crowded Greyhound/Palm Springs weekend, will have about 72 million viewers in its first four weeks — which is great, with the gigantic caveat that all we know about these viewers is that they watched two (2) minutes of The Old Guard. (By the way, all three of these aforementioned movies are good. I’m glad people are watching them. Just because their distributors are being totally weird about who watched what shouldn’t reflect poorly on the films themselves.)

In the past, we could scoff at such vague or misleading announcements because they were relatively inconsequential to the question of what was a hit or not — because that was still largely determined by the domestic box office. But the truth is that our definition of a hit movie is rapidly changing. Part of the reason for this is obvious: The domestic box office has been wiped out by a literal plague and is unlikely to come back soon; in its absence, streaming numbers have gained greater significance, as have VOD numbers, be they of big studio titles or “virtual cinema” indie releases.

But this trend had started well before COVID-19 hit. Two of 2019’s most talked-about films, The Irishman and Marriage Story, were released into theaters by Netflix, but we didn’t get any official box-office numbers for them. A month or so later, they started streaming and, judging by the number of memes they generated, became viral phenomena. We never really knew if they were hits; we just sort of had a sense that they were. (Netflix now says that the first two [2] minutes of The Irishman were watched by 64 million people in its first month. This is good, I think?)

Obviously, the views themselves aren’t necessarily indicative of these streaming companies’ bottom lines. Netflix doesn’t make money off an individual viewing of, say, Da 5 Bloods, and Apple doesn’t make money off an individual viewing of, say, Greyhound. They make their money when you and I choose to subscribe to those services, presumably because of must-see content like, say, Da 5 Bloods and Greyhound.

Still, the way a company measures success tells us a lot about how it understands its core business. You can see this at work in the way the domestic theatrical box office has transformed over the past several decades. As opening weekends have gained greater significance in a film’s financial success, the studios have become elaborate marketing operations. A big opening weekend is not a sign of quality (since nobody’s seen the movie yet, besides critics, and nobody cares what we think) but a triumph of the marketing department’s ability to get those first butts in those first seats at those first showings. So much so that, nowadays (at least pre-pandemic) we know if a picture will be a hit based on its Thursday-night previews alone. Similarly, that it chooses to focus on those first two (2) minutes tells us that Netflix still views itself primarily through the prism of its technological ability to get its content in front of the right viewers — that dreaded Algorithm, which increasingly sounds less like a program and more like an ill-defined storybook villain.

In Hollywood, “data” has always involved a certain amount of numerical witchcraft and sophistry. Some of it’s about creating the illusion of success, or at least the avoidance of public failure. Some of it’s about not paying artists and craftspeople their fair share of back-end profits, which is a whole other conversation. (And don’t even get me started on the international box office, where a lot of the numbers appear to be totally cooked.) While the last thing the box office can tell us is whether a movie is any good or not, in an era when gargantuan tentpoles have driven just about everything else out of the marketplace, that is exactly how some viewers use it. Some of this is understandable: Our society loves hits. Top 40 countdowns, lines snaking around blocks, packed houses, books flying off shelves at special midnight openings — the hit is one of the building blocks of American culture. We seek out hits. We dream of writing or recording or starring in hits. And it’s not all a bad thing: Yes, hits speak of consumerism, but they also speak of the way we connect.

So what happens when there are no more hits? Or at least, no reliable way to tell what’s a hit and what’s not? Because that’s sort of where the movies find themselves right now.

One of the saddest things about these streaming numbers is how alienating it all seems, all those millions of people sitting at home, many of them by themselves, now quantified by whether they sat still enough to watch something for two (2) whole minutes. It’s all so weirdly soulless and corporate. It doesn’t say, “We made something you might enjoy.” It says, “We suckered you into clicking a button.” It’s the brazen language of a huckster. And let’s face it, that’s where the box-office numbers were headed, too: “We made you come out opening day, but we don’t care if anybody shows up next week. We’ve got our money and we’re getting the hell out of Dodge.”

Ironically enough, Netflix and other streamers have an opportunity here to insert some sanity and humanity back into the discourse. Regardless of whether they’re releasing it or not, they have access to all sorts of data about how we view these movies and shows. In 2019, we learned that Netflix grouped users into three overlapping buckets: starters (the two [2] minute people), watchers (the 70 percent people), and completers (people who finished at least 90 percent of a movie or series). At the time, Netflix was making the watcher data public and calling those views, while it shared the other data with creators to help them make better Netflix content. Why did Netflix switch to defining views by the significantly dodgier metric of starters who’d watched two (2) minutes of a given title? It may well have been an attempt to goose the company’s numbers in the face of competition from all the other streaming services that have emerged over the past year or so.

But really, it seems clear to me (and probably to you) that the real viewers should be the completers: The people who went (almost) all the way with a movie or show. The people who not only chose to watch it, but also chose to finish it. There are probably good reasons why Netflix doesn’t make those numbers public. Last year, Nielsen (which does track some streaming data) reported that only about 18 percent of viewers in the U.S. finished watching The Irishman on its first day. That sounds, frankly, terrible — but apparently, it’s comparable to noted viral hit Bird Box (also 18 percent) and higher than plenty of other big Netflix titles. In other words, it’s embedded into the very nature of a streamer like Netflix that people will just click around and sample options without bothering to finish them, or even get all that far into them. That right there tells us that the two (2) minute stat is largely worthless. But it also tells us something constructive too: In a world where it’s all too easy to switch to another program, or to stop watching halfway through and not come back, the stats on how many people chose to watch all the way through matter a great deal.

In a theater, it’s hard to abandon a movie you’re watching, even if you hate it. You paid for it, for starters, and you’ve already made the time commitment; it feels like an admission of defeat. Plus, there are all those people in the row you have to stumble your way through. But on Netflix, on Hulu, on Disney+, and on Apple TV+ (and on Peacock, and on HBO Max, and on Criterion, and …), it’s quite easy, and, indeed, people seem to be taking advantage of that ability. I don’t personally love that phenomenon — I’m a big believer in sitting through whatever it is I’ve chosen to watch, which is why I am a person who has seen Human Centipede 3: The Final Sequence all the way through — but I do like the fact that this data tells us more than just who pressed which button. The completers, in other words, aren’t fairy-tale numbers designed to burnish stats. It’s real data that tells us not just whether a movie or show made it to the right people, but also whether those people stuck with it or not — maybe even, gasp, enjoyed it. That would actually make it a far more accurate gauge of audience appeal than traditional box-office stats. And it would give us a new and valid way of thinking about what constitutes a hit in our Age of the Pod.