The Democratic National Convention is one of the best television series I’ve seen this year.

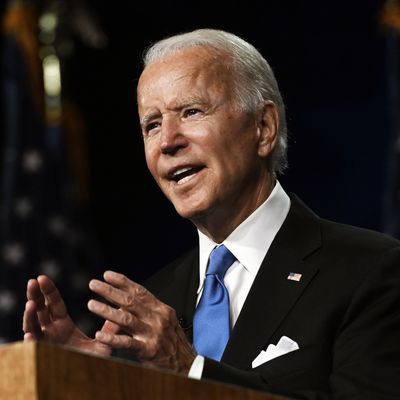

That is a weird sentence. It is a sentence I would never have imagined writing even six days ago. But it is, to borrow a phrase from Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden’s acceptance speech, the unvarnished truth.

The four-day semi-virtual convention, format courtesy of COVID-19, turned out much better than most of us would have expected. Thursday, the closing night, when Biden officially accepted the party’s nomination for president, cast the widest tonal net of the week. Against all odds, it mostly worked.

The two-hour broadcast included a video tribute to the late John Lewis and another signature Sarah Cooper impression of Donald Trump. It provided numerous homages to Biden’s late son Beau, a jovial Zoom chat between most of the previous Democratic presidential candidates, and a joke about Away, Amtrak’s onboard magazine, that was delivered by the night’s host, Veep star Julia Louis-Dreyfus. There was an adorable segment in which Steph and Ayesha Curry quizzed their daughters about democracy, and a tear-inducing moment in which a teenage boy named Brayden Harrington, who befriended Biden because they both share a stutter, delivered a speech endorsing the nominee on national television.

Then there was Biden’s speech, which, unlike Kamala Harris’s the night before, was filmed entirely in a tight shot of the former vice-president that slowly pulled in tighter as his remarks continued. Speaking at times forcefully and at times in a reassuring, grandfatherly near-whisper, Biden, flanked by a pair of American flags, tried to make each viewer feel like we were one of those apparently numerous people with whom he might be inclined to share his personal cell-phone number. The steady intimacy of the framing really helped in that regard. If Biden’s strength, as the convention told us repeatedly, is the way he connects with Americans one-on-one, the fact that he delivered his speech in this visual context allowed him to play to his greatest asset.

After quoting a poem by Seamus Heaney — “History says / Don’t hope on this side of the grave / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history can rhyme” — Biden said, “This is our moment to make hope and history rhyme.” It was a line not only straight out of Irish poetry, but straight out of The West Wing. It also served, in a way, as a thematic thread that ran throughout the whole convention. In its messaging and the way that messaging was conveyed, buoyed by the socially distanced format the pandemic required, the 2020 DNC effectively tapped into America’s nostalgia fixation, but in a way that upended traditional notions of nostalgia, as well as the “let’s go back to the good old days” approach that Trump employed in 2016. Trump engaged, and still engages, in time-machine nostalgia, the kind that would take us straight back to 1955, possibly in a DeLorean. The Biden campaign leans more toward what I’ll call Mad Men Kodak Carousel nostalgia, something, to riff on Don Draper’s words, that’s more delicate but still potent. The fact that this year’s convention took something familiar and had to present it in a new way tied beautifully into that particular strain of nostalgia.

Four years ago, Trump ran on the slogan “Make America Great Again,” a fact that is impossible to forget since he and his followers are still committed to the MAGA acronym four years later. (I guess “Transition to Greatness” doesn’t look as good on a red baseball cap.) At the Republican National Convention in 2016, Trump closed his acceptance speech by banging hard on that piece of branding. “To all Americans tonight, in all of our cities and in all of our towns, I make this promise: We will make America strong again,” he said. “We will make America proud again. We will make America safe again. And we will make America great again.” Of course, the prouder, safer, greater America Trump envisioned was one based on white-centered fantasies of what America used to be, a “Suburban Lifestyle Dream” that Trump continues to cling to even now. But clearly, as we saw back then, conjuring racist, outmoded ideas about some wonderful American yesteryear holds a certain sway over some voters.

The fact that Joe Biden became the Democratic nominee presented a natural opportunity to tap into a different sort of nostalgia: a yearning for the way things used to be four years ago, before Trump got elected, when Biden was veep and Barack Obama was our president. As Don says in the season one finale of Mad Men during his pitch to executives at Kodak, nostalgia “takes us to a place where we ache to go again.” Certainly many Americans, especially in the midst of this horror show of a year, ache to go back to pre-Trumpian times. At a regular convention, where all the delegates were gathered in one place, Barack and Uncle Joe undoubtedly would have taken the opportunity to stand together on a national stage, clasp hands and wave to a cheering crowd. But with the standard convention format scrapped, the DNC found other ways to transport us back to the Obama–Biden years. Wednesday night’s program included a portion of the 2017 Medal of Freedom ceremony where Obama presented Biden with that high honor. Multiple speeches mentioned the accomplishments of that administration as a contrast to what we have now. The mere presence of both present-day Barack and Michelle giving pointed speeches during the three-day windup to last night evoked memories of living in a country where the folks in charge were rational and compassionate.

Nostalgia was tapped in other ways, too. A portion of Bruce Springsteen’s “My City of Ruins,” a song that became popular 9/11, was used repeatedly in a series of videos that ran throughout the convention. Anyone old enough to remember the immediate post-9/11 era and the blip of time when it genuinely felt like every American had each other’s backs may have felt a nostalgic tug upon hearing Springsteen’s voice repeatedly croon, “Rise up.” Using that song as often as the producers did was a deliberate invitation to call up our memories of unity.

Even the emphasis on decency and empathy, words used many times to describe Biden, was a reminder of how easy it used to be to take such things for granted and how starved we are for them now. When Biden promised in his speech to defend America at all costs and expressed sincere condolences to those who have lost loved ones to the coronavirus, he was doing what any good leader would hopefully do. But because we have rarely heard such straightforward, empathetic rhetoric during the past four years, even those comments conjure a nostalgic ache.

The convention also reminded us that memories of the past, both distant and recent, are not mere remembrances of a wonderful time. Repeatedly over the four days, we were reminded to reflect back on everything that has happened over the past four years as we prepare to vote. “Close your eyes,” Biden said in his speech Thursday night, referring to the recent third anniversary of the white supremacist marches in Charlottesville. “Remember what you saw on television and remember seeing those neo-Nazis and Klansmen and white supremacists, coming out of fields with lighted torches, veins bulging, spewing the same anti-Semitic bile heard across Europe in the ’30s.”

In moments like that, and even in the biography of Biden, we are invited to flash back to the past with our eyes open to its harsher realities. Young Joe Biden may have grown up in the sort of loving middle-class family that smacks of American glory days. But his dad lost his job at one point, and later in life, Biden would eventually lose his first wife, a baby daughter and, later, one of his sons. Biden’s narrative ties in very neatly with the fact that no American history, national or personal, is pretty or perfect. It’s messy and it leaves scars. Did the convention touch on every messy aspect of Biden’s past, like the fact that he presided over the Clarence Thomas–Anita Hill hearings, or the fact that Biden has been accused of making women uncomfortable and, in one case, assault? No. This was Mad Men Kodak Carousel nostalgia: delicate, potent, but also, like all political conventions, an advertisement.

Maybe the smartest thing the DNC did with this convention was to repeatedly connect the past to our potential future. Instead of merely wallowing in yearning for what used to be, the convention emphasized a desire to pick up where we left off four years ago and then keep moving forward. In other words, it harnessed nostalgia for the past, but a specific past when many Americans felt like the future still had promise.

On Thursday, the tribute to Lewis included footage of the civil-rights movement that segued directly into images of this year’s Black Lives Matter protests. On Wednesday, the night that Kamala Harris became the first Black and South Asian woman on an official Democratic ticket, a tribute to women in politics took viewers from the suffragette movement to the Women’s March. Obviously many women were disappointed that, after almost getting our first female president, we’ve gone right back to nominating an old white man for the job. The convention did what it could to compensate for that by giving women the last word on three of the four nights; their speeches, particularly Michelle Obama’s, were some of the most memorable highlights of the whole event. That said, Democrats could have done a better job of highlighting their younger — meaning under the age of 50 — stars who represent the future of the party. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez deserved to be heard for more than just the 60 seconds she spent on the formality of introducing Bernie Sanders as a candidate. Julián Castro also was deserving of a speaking slot and didn’t get one.

In his speech Wednesday night, President Obama said that Biden “sees this moment now not as a chance to get back to where we were but to make long overdue changes.” Obama was referring specifically to the economy, but that statement applies to pretty much the entire message of the convention, which also took great pains to feature ordinary Americans as well as political leaders from around the country who are Black, Latinx, Asian American, Native American, gay, trans, and disabled. The Kodak Carousel goes “backward and forward,” Don Draper noted, and goes “around and around and back home again to a place where we know we are loved.” Emotionally and thematically, that’s what this convention did.

By the time it ended with a socially distanced fireworks display that made it feel like the Fourth of July, the only thing left to say to American voters, whose support will be courted during next week’s four-day Republican National Convention, was the same thing Duck Phillips wryly said to the Kodak executives after Don wowed them with nostalgia: Good luck at your next meeting.