This article was originally published on November 24, 2020. We are recirculating it now timed to the release of Trap.

The Christmas rom-com is a delicate genre. Its innumerable entries fail far more often than they succeed, usually in attempts to re-create the rare triumph of a predecessor. For every The Holiday, there is a Holidate; for every The Family Stone, there is a Love the Coopers; and so on forever. Which is why I was equal parts terrified and thrilled when I heard about Clea DuVall’s Happiest Season, an attempt to elevate the genre by doing what everyone should have been doing all along: making it gay and centering it on a bleached-blonde Kristen Stewart desperate to propose to her tall girlfriend, Mackenzie Davis. As a queer Jewish woman obsessed with both Christmas and Kristen Stewart, this movie felt tailored to me specifically; its failure would, not to be gay, ruin my life.

Which is why I was relieved when Happiest Season turned out not only to be cute and heartwarming but also to feature Kristen Stewart in a low-cut tuxedo and an undone tie and let her walk around drunk for a while. My only real quibble with the film is its central plot point: Davis’s Harper is too scared to tell her conservative family that she’s gay and dating Stewart’s Abby. In the process, she nearly alienates Stewart. I don’t want to minimize anyone’s struggle, but I have to believe there is no family on earth that would be upset to learn one of its constituents is dating Kristen Stewart. I don’t care if your dad is a megachurch pastor. Even he would be like, “… okay, NICE.”

But I digress. I’m here to talk about something else. Most of Happiest Season is high-key gay in that it centers on two lesbians making out in a basement in secret. But there’s one (arguably, but not actually … you’ll see) low-key gay moment that struck me as particularly inspired on DuVall’s part. Early on, Harper’s uptight mom (Mary Steenburgen) is showing Abby (whom she believes to be Harper’s “orphan roommate”) around their home, the sort of stately redbrick manse that is a requirement for all Christmas-movie families. The tour concludes in Harper’s old bedroom, where her kooky sister, Jane (Mary Holland), wrenches open Harper’s closet door to reveal a series of pasted-up photos of various nondescript hunks. None of the men are remotely recognizable, save for one large central photo of 1998’s hottest bachelor, Joshua D. Hartnett. “Looks, talent, brains, Hartnett’s got it all!” reads the poster, which has seemingly been ripped from a Teen Beat. Abby, trying not to laugh, breathes, “Wow.” Jane presses her face against Josh’s singed brow. “I know, right? Is it hot in here, or is it just him?”

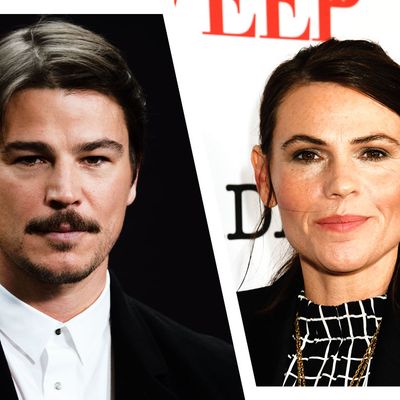

The scene is meant to indicate just how deep in the closet Harper is and has always been, even going so far as to painstakingly decorate her own literal closet with photos of oiled-up men. But as I watched the moment unfold, it dawned on me that perhaps there’s another layer beneath that surface reading. Queerness is so often about subtext; I have to believe that writer-director DuVall, a queer woman whose second middle name is D’Etienne, would not place a photo of Josh Hartnett in a movie without imbuing it with multiple meanings. After all, the two once co-starred in The Faculty, a movie about the importance of questioning the motives, and alleged species, of heteronormative authority figures. More important, they look very similar. I began to wonder if, by including this poster in Harper’s closet, DuVall was nodding to the fact that, for a certain subset of millennial women, Josh Hartnett was a quiet stepping-stone on the way to true queerness, i.e., lusting after Clea DuVall.

As a young, burgeoning bisexual who thought her feelings toward Topanga on Boy Meets World were pure hair envy, my feelings about Hartnett were, to put it gently, rabid. One of my favorite youthful activities was to pore through magazines cutting out photos of Hartnett’s sturdy face and then gluing them onto poster boards, which I then placed in prominent spaces around my bedroom. Although the internet existed at this point in time, it was hardly the Josh Hartnett SEO machine that it is today, so I got my Hartnett news via mail from my mom’s friend DeDe, who lived in Minneapolis — Hartnett’s hometown, which, at one point, considered his every move to be worthy of newsprint. For many years, I followed his career through its especially sharp twists and turns: the Trip Fontaine “Magic Man” years; the dog-tag Pearl Harbor era; that time he fought over Leelee Sobieski with Chris Klein and somebody died of cancer (?); his sexy Chicago romantic thriller; the time he made Shannyn Sossamon come using a flower; and even a few of the movies he made when he decided he didn’t want to be famous, then decided he did want to be famous but then it was too late, and now that he’s not really famous anymore, every time people interview him they’re like, “Wait, why aren’t you famous anymore?”

But back to the gay part. Hartnett’s appeal was obvious to anyone growing up in the ’90s with any sort of libido: the squinting eyes, the quiet brooding, the swoopy hair, the unibrow that indicated he did not care that he had a unibrow. It would be difficult for anyone, even megachurch pastors, to avoid feeling an attraction to Joshua Hartnett at his peak. But the working theory I developed upon watching Happiest Season is that he was particularly attractive to young, confused gay women growing up in the ’90s. Again, in large part, due to the fact that he looked a lot like DuVall — who, thanks to But I’m a Cheerleader, was a burgeoning queer icon herself at that point despite still being in the closet (see what I mean about the layers??).

It certainly helped, too, that Hartnett’s movies were shot through with queer subtext: Both Here on Earth and Pearl Harbor are about two men who cannot be together, so they fight over Kate Beckinsale and Leelee Sobieski; he’s also in a movie about a British hairdressing competition. And viewed from space, Hartnett’s career arc is itself something of a queer narrative: He burned so brightly and then disappeared into exile in Europe, much like Oscar Wilde. No matter how you slice it, I realized, Josh Hartnett was the perfect gay gateway drug.

To test this theory, I reached out to every queer woman I have ever met and asked them, “Did you, at one point on your gay journey, have an obsession with Josh Hartnett?” “I didn’t know this was the question I had been waiting for all my life, but here we are,” said Jessica. “I was absolutely into him. I just rewatched The Virgin Suicides for the first time in 15 years and remembered how insanely into him I was when the movie came out. He’s in the Heath Ledger–Keanu Reeves–Tom Hardy school of men that women who are into women find hot.”

Nearly all my friends’ replies confirmed in one way or another that 40 Days and 40 Nights is a key component in Hartnett’s queer appeal — that the movie is canonically gay in a way that also turned all my friends gay, in the same way that all video games make people murderers. Haley said she “think[s] all the time about that scene in 40 Days and 40 Nights when he makes Shannyn Sossamon come from a feather [Ed. note: It’s a flower, but a feather is equally gay]. Everything about that was gay, thanks!” At first, Teo seemed loath to admit her lust for Hartnett: “Okay … honestly? Yes, I was into him. Not as intensely as Orlando Bloom, but it existed for me.” But she had a lot to say about 40 Days’ lesbian resonance: “Honestly, I think what was going on there is that he was in that movie about the man who tries not to come for 40 days and 40 nights, and even though, from what I remember of that movie, it is explicitly misogynist, it’s still a very lesbian way of thinking about sex. That stupid flower scene was the only PG-13 lesbian sex scene of the early 2000s.” She added that he “also has a very soft butch look in that movie.” Our conversation quickly turned into a discussion of Sossamon’s superior hotness. “That girl looks like a girl who should be dating a lesbian, and Josh Hartnett looks like a lesbian,” concluded Teo.

Days later, I had the opportunity to speak to Sossamon herself for a different story and decided to spring the same question on her: Did she know that she and Hartnett, together, represented a bisexual awakening for millions* (*unsubstantiated) of women around the world? “That was only my second movie, but Josh is very charming. I totally get it,” she said, expertly dodging the question. “I haven’t talked to him in a long time, but I remember he’s incredibly charming and warm.” Sensing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, I asked what she recalled about filming the orgasm-with-a-flower scene. “I was nervous because I was like, How exactly are we going to do this?” she said, laughing. “In my real life, I can’t imagine in a million years [orgasming via flower]. Everyone’s preferences are different. I remember being on set, it was very difficult not to laugh. I was like, ‘Who would do this?’ And then the director kept saying, ‘You know, some people might, some people might.’ And I was like, ‘All right.’”

There were, however, some people I polled who took specific issue with 40 Days and 40 Nights, suggesting that Hartnett’s queer appeal lay elsewhere. My friend Claire, who “loved him in The Virgin Suicides and other things when he was younger,” said, “I vaguely remember being annoyed by that movie, like he was betraying me by doing that character.” When I asked why, she said, “I think I liked the denial aspect of it (longing/celibacy — VERY queer), but he was kind of a frat bro in a way that I didn’t like, even though he finds his sensitive side.” She added that, while she “preferred the longing Josh Hartnett, who doesn’t get laid or sully himself,” he “does feel like a queer root” and that his “Penny Dreadful character hooking up with Dorian Gray was the hottest thing ever.” (See below.)

Without prompting, several friends brought up the fact that Hartnett and

DuVall are twins. “I do think there’s something sort of girlie about him,” said Marian. “He looks like the dyke from But I’m a Cheerleader a little bit.” My friend Jamie did not want to get into it any further, except to say, “Ya, he’s gay. Everyone is gay, Rachel. You can quote me on that,” followed by a flamingo emoji. (To be clear, I do not think Hartnett himself is gay, though I don’t think he’s not not gay. Josh, call me. Just to tell me if you’re gay.)

There were a few outliers on the Josh Hartnett Queer Root front. “My personal opinion would be no, though he does have the Leo squint, and maybe it’s all in the squint,” said my friend Hallie, referring to the ne plus ultra bisexual root, young Leonardo DiCaprio in Romeo + Juliet. I confirmed that squinting was gay canon. “Squints make you gay,” she said. “If you squint hard enough, everyone is gay.” My Australian friend Estelle took issue with Hartnett’s irreducible Americana energy. “He came across as too wholesome America for me,” she said. When I asked who had been her Josh Hartnett, she replied, “Unintimidating guys like JTT and Jonathan Brandis (RIP). Probably most telling is Elijah Wood.” Madison said she was too young to have appreciated Hartnett in his prime, and Clio, who doesn’t watch movies, said, “Who is Josh Hartnett again?”

To balance out my very scientific, unimpeachable study, I reached out to my only 100 percent straight female friend, Hazel, and asked if she had ever been into Hartnett. “I was not,” she said. I then texted a bunch of my gay male friends and asked the same question. Most expressed ambivalence or light appreciation. “Okay, I am weird (not into Brad Pitt), so take this with the tiniest grain of salt imaginable: never into him,” said Dan. His partner, Chanan, agreed. “No strong feelings but only because he reminds me of Ashton Kutcher,” he said. (He did not elaborate.) My friends Ryan and Ryan, who contractually must always be quoted as one person, said they “probably did a little” because Hartnett “kind of had Ethan Hawke vibes: tall and scraggly, kind of dirty looking but not filthy. I kind of forgot about him until just now, though.” (I take issue with the description of Hartnett as “scraggly”; he is more square.) The one outlier here was my friend David Michael, who said, “This brings me back to stealing my sister’s magazines with shots from Pearl Harbor. He’s very pretty and would obviously be a gentle lover.”

Which, of course, brings us back to the stolen magazine shot in Happiest Season. It’s possible that the poster is just a poster and that the film is meant to be read purely on a surface level, ignoring all subtextual implications about how Tiger Beat was secretly pushing the gay agenda to its legions of horny tween fans. But I believe gay Christmas intellectual Clea DuVall wouldn’t place Josh Hartnett’s SpongeBob-shaped visage in her movie without first considering the profound implications of doing so. I believe she was doing whatever the progressive version of dog whistling is at all of us young, queer millennial girls, letting us know she knew that when we were all papering our rooms with photos of Josh, we secretly wanted to be papering our rooms with photos of her.